Many of the Lady’s Magazine project’s followers do so because they are interested in fashion. That’s hardly surprising, really. The periodical’s fashion plates, reports, embroidery patterns and the many hundreds of essays it published on the allure and perils of sartorial consumption are the very things that first brought me to the Lady’s Magazine as a PhD student writing on eighteenth-century dress back in the late 1990s.

From its very first issue in August 1770 the periodical signalled that regular ‘fashion intelligence’ in the form of engravings and written descriptions of ‘the covering of the head, or the clothing of the body’ would be an indispensible part of its format (1). It was, though, a promise the magazine struggled to made good on. Although those essays on dress, as well as attention to the costumes of other nations in travel writing and an antiquarian interest in dress in works of history, are recurrent features in the periodical from its inception, fashion journalism, as we would call it now, is conspicuously absent in the magazine in its first thirty years.

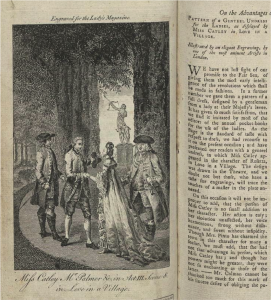

LM 1 (Nov 1770). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The first fashion report, of sorts, the magazine published was in November 1770 and was accompanied by an engraving showing the actress Ann Catley in a scene from Love in a Village. In it, the magazine’s editors remarked that they had not lost sight of their promise to provide readers with the latest trends, but they struggled to live up to their stated objective of purveying metropolitan fashions to those in the provinces in subsequent issues (170). The first recognisably modern fashion report was not published until February 1773 and is typical of the economical to the point of obscurity, staccato prose style that would characterise the genre at this time: ‘The hair in front, with small puff curls; a close cap, made with wings; narrow ribbon, in small puffs; double row of lace; ditto lapelled …’ (72). Next month the magazine followed with an account of full dress and undress for March, allowing the unknown author to make comparisons that suggested fashion’s progress, even month by month, would be bewilderingly relentless – ‘Hair front lower, puff curls or none …’ – without the guiding hand of the magazine to steer readers through its labyrinthine course (152).

The magazine’s fashion reporters were as impermanent as the quickly outmoded styles they described, however, and readers wanting to know if hair fronts would plunge lower still (gasp!) would have to wait until September for the next update, and thereafter for another four issues until the Supplement to learn more. The problem got a good deal worse before it got better. A contributor known as Charlotte Stanley was by far the most reliable of these figures, although that’s not saying much. Her career of fashion reporting for the magazine began in March 1774; she produced another three reports across the rest of the year but did not resume her column until March 1776 (after the magazine apparently received a barrage of complaints from readers). She would produce only one more report that year. In 1777 and 1778 no fashion reports appeared in the magazine at all, but readers would not let the matter lie. As late as June 1782, a regular contributor to the magazine, Henrietta C-p-r, was begging Miss Stanley to once again bestow her ‘elegant favours’ upon her readers. The request fell on deaf ears.

In fact, it was not until the 1790s that fashion reports (usually glancing over the channel to observe the shifting styles, as well as politics, in France), became a much more regular feature. In 1800 would they become a permanent monthly fixture with the introduction of an elegant coloured fashion plate of Paris fashions usually taken (unacknowledged) from Le Journal des Dames et des Modes (1797–1839). (I’ve had a lot of fun playing ‘find the fashion plate’ in the past few weeks.) London reports and plates, commissioned directly by the magazine, did not follow until 1805. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, fashion plates were an at best an irregular feature, largely it seems, because of the expence they involved. But it was an expence that could not be avoided after the founding on Vernor and Hood’s pocket-sized and elegant rival, the Lady’s Monthly Museum (1798–1828), with which the Lady’s would later merge and which contained monthly coloured plates. In a bid to keep up with its new and unwelcome competitor the Lady’s Magazine raised its price from the sixpence it had charged for thirty years to a shilling an issue in part to cover the costs of fashion plates.

In fact, it was not until the 1790s that fashion reports (usually glancing over the channel to observe the shifting styles, as well as politics, in France), became a much more regular feature. In 1800 would they become a permanent monthly fixture with the introduction of an elegant coloured fashion plate of Paris fashions usually taken (unacknowledged) from Le Journal des Dames et des Modes (1797–1839). (I’ve had a lot of fun playing ‘find the fashion plate’ in the past few weeks.) London reports and plates, commissioned directly by the magazine, did not follow until 1805. Before the first decade of the nineteenth century, fashion plates were an at best an irregular feature, largely it seems, because of the expence they involved. But it was an expence that could not be avoided after the founding on Vernor and Hood’s pocket-sized and elegant rival, the Lady’s Monthly Museum (1798–1828), with which the Lady’s would later merge and which contained monthly coloured plates. In a bid to keep up with its new and unwelcome competitor the Lady’s Magazine raised its price from the sixpence it had charged for thirty years to a shilling an issue in part to cover the costs of fashion plates.

Both publications faced further fashion competition from the launch of John Bell’s sumptuous, royal octavo La Belle Assemblée, or Belle’s Court and Fashionable Magazine, which launched in February 1806 and also later merged with the Lady’s. Bell’s magazine carried rich and varied contents, but remains best known for its dedicated and substantial, multi-page monthly fashion section originally entitled the ‘Second Division’. In the first issue alone this section included: reports on ‘London Fashions for the Present Month’; ‘Parisian Fashions, for February’; ‘General Observations on Fashions and the Fashionables’; ‘Three whole length Portraits, and four Head Dresses of the London Fashions’; ‘Five whole length Portraits of Parisian Fashions’; and four embroidery patterns. None of the fashion plates was coloured, but this would change just ten months later when, in response to competition from his son John Browne Bell’s Le Beau Mode, and Monthly Register (1806–9), Bell Senior offered La Belle Assemblée in two formats: 2s 6d for issues containing uncoloured engravings, and 3s and 6d for those with coloured fashion plates.

LM 58 (Nov 1827). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Cambridge University Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The Lady’s Magazine could never compete fully with the high production values of Bell’s periodical, which even at its lowest price point cost twice as much as George Robsinson’s monthly magazine. But La Belle Assemblée’s influence can nevertheless be felt in the Lady’s Magazine’s and Lady’s Monthly Museum’s fashion coverage. One of its most important developments was its emphasis upon named fashion authorities, a trend that Rudolf Ackermann’s Repository of Arts (1809–29) also followed. Professional dressmakers and milliners such as Madame (Margaret) Lanchester and then Mrs M. A. (Mary Ann) Bell featured prominently as the ‘inventresses’ of the fashions La Belle Assemblée and the Repository visualised and described, while advertisements for these women’s fashionable London establishments featured in their back pages. By the 1810s, the Lady’s Monthly Museum and Lady’s Magazine had followed suit by looking to their own fashionistas – Miss Macdonald of 50 South Molton Street, Mrs W. Smith of 15 Old Burlington Street and Miss (Mary Maria) Pierpoint of Portman Square – to provide direction on the latest styles with instructions.

The reliance upon the expertise of these women changed the magazine’s fashion content in various ways that I have been trying to think through and write about in a book I am working on about the Lady’s Magazine. I’ve now worked out what I want to say about that, but as I was mulling it over and pondering the way the magazine’s fashion content changed over time, I couldn’t stop thinking about Madame Lanchester, Mrs Bell – interchangeably referred to in various sources as John Bell’s wife or daughter-in-law – and Miss Pierpoint. Who were these women? Why do we know so little about them now when in their own day their name commanded such widespread respect from the fashion conscious readers of the Lady’s Magazine and its competitors? I don’t yet have all the answers and there is much more I hope to be able to find out about these women, but after many hours (confession: it might actually be days) diving into the newspapers and digging around on Ancestry, I know a good deal more than I did and I plan to share some of these insights in part 2 of this blog post next week. Hope you’ll join me then!

Prof. Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent