This conference season has been busy for Team Lady’s Magazine. In the past two weeks alone, we attended two events that we were looking forward to very much, because we were to soft-launch our index there in anticipation of its official publication in September: the annual conference of the European Society for Periodical Research (ESPRit) at Liverpool John Moores University, and ‘Victorian Periodicals Through Glass’, held at the Athenaeum Club in London. Writing papers and presenting them, and giving the hard work of your colleagues the attention it deserves, can be exhausting work, although I would be less tired if I had the discipline to go straight to bed after conference dinners. Furthermore, when the conferences in question are as good as these two were, they are also very inspiring. We went home with ideas for last-minute tweaks to the index, with a better understanding of how the index will likely be used, and with a renewed sense of how the diverse contents of the Lady’s Magazine remain topical. One subject discussed at both events was the importance of transnational contacts to cultural production, throughout history, even for phenomena that may at first sight seem of a strictly national interest. I am thinking in particular of the panel of our friends of Agents of Change (Ghent University) at the ESPRit conference on their comparatist study of female-fronted socio-cultural transformation across the European periodical press between 1710 and 1920, and the keynote paper by Prof. Regenia Gagnier in London (doubling as this year’s Sally Ledger Memorial Lecture) on the afterlife of Wilde’s Soul Of Man Under Socialism (1891) in publications of Asian political movements. These made me reconsider a fascinating aspect of the Lady’s Magazine that has as yet received little attention: the many translations furnished by its vibrant community of reader-contributors.

This conference season has been busy for Team Lady’s Magazine. In the past two weeks alone, we attended two events that we were looking forward to very much, because we were to soft-launch our index there in anticipation of its official publication in September: the annual conference of the European Society for Periodical Research (ESPRit) at Liverpool John Moores University, and ‘Victorian Periodicals Through Glass’, held at the Athenaeum Club in London. Writing papers and presenting them, and giving the hard work of your colleagues the attention it deserves, can be exhausting work, although I would be less tired if I had the discipline to go straight to bed after conference dinners. Furthermore, when the conferences in question are as good as these two were, they are also very inspiring. We went home with ideas for last-minute tweaks to the index, with a better understanding of how the index will likely be used, and with a renewed sense of how the diverse contents of the Lady’s Magazine remain topical. One subject discussed at both events was the importance of transnational contacts to cultural production, throughout history, even for phenomena that may at first sight seem of a strictly national interest. I am thinking in particular of the panel of our friends of Agents of Change (Ghent University) at the ESPRit conference on their comparatist study of female-fronted socio-cultural transformation across the European periodical press between 1710 and 1920, and the keynote paper by Prof. Regenia Gagnier in London (doubling as this year’s Sally Ledger Memorial Lecture) on the afterlife of Wilde’s Soul Of Man Under Socialism (1891) in publications of Asian political movements. These made me reconsider a fascinating aspect of the Lady’s Magazine that has as yet received little attention: the many translations furnished by its vibrant community of reader-contributors.

In standard accounts of long-eighteenth-century print culture, most notably in the otherwise admirable history by Prof. Kathryn Shevelow, there is a strong emphasis on the domestic ideology allegedly advocated by the Lady’s Magazine.[1] Scholars sweepingly reducing the complex ideological debates within the magazine to this particular message may not have read far beyond the subtitle of the magazine, in which it styles itself ‘Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to their Use and Amusement’. This does suggest a form of self-censorship calculated to reinforce strict gender norms so as to instil in its ‘fair’ readers their prescribed role in the household, and, of course, a secondary sense of ‘domestic’ is ‘of or pertaining to one’s own country or nation; not foreign, internal, inland, “home”’.[2] Nevertheless, as Jennie Batchelor has shown, the content of the magazine was much broader than this suggests, and for instance catered to the interest in other cultures and nations of a wide array of readers, most of whom will never have left the British Isles. There are hundreds of ‘anecdotes’ and ‘accounts’ of foreign cities and cultures, and many translations, often submitted by reader-contributors. In every volume of the magazine at least a number of items of foreign origins even appear in their original language.

Jenny DiPlacidi, who has categorized all contributions for our index, has made it very easy for us to find out how many items in French appeared in the magazine. Between 1770 and 1790 there were no less than 91 items in another language than English. Three of those are Italian, and all others are in French. While these relative proportions may be surprising, the choices of these two particular languages is soon explained. Italian was seen as a language of culture, amongst other reasons because it was the language of opera seria, and was additionally popularized through the parmesan-dusted verse of the Della Cruscans (also featured—need it still be said?— in the Lady’s Magazine), and shelves have been written on the enduring love/hate relationship between Britain and France. These items come in a variety of genres, but tales and conduct pieces predominate; two genres that are of course very common in the magazine in general. The items in foreign languages seem to have been nearly exclusively appropriations.

The foreign-language items did not only function as reading material on par with the English content, but evidently had a particular pedagogical use. Nearly all are translated by readers who submit their efforts for publication in subsequent issues. An editorial footnote stating that ‘a translation is requested’ often appears to encourage this practice. Over a period of a staggering ten years, between 1774 to 1784, loyal reader-contributor ‘Henrietta R-’ submitted instalments from Abbé Séran de la Tour’s Histoire d’Épaminondas (1739), and these were diligently translated by a cohort of other readers who kept up quite well with the pace of publication of the serialized original. It finished several years before the first one-volume translation of this work (a different text) is published, in 1787.

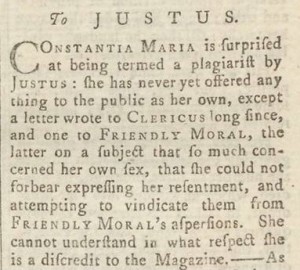

The fact that often more than one submitted translation of the same foreign-language original is published indicates that the quality of the translation was at least as important as the content of the original piece. It is clear that these pieces were perceived as a challenge by the readers, much in the same way as the many puzzles, and like these served to consolidate the magazine’s readership and gave readers an opportunity to exercise and demonstrate their ingenuity. In April 1782, a regular reader-contributor signed ‘Maria’ submitted an unattributed poem in French, which I have identified as an extract from Beaumarchais’s Le Barbier de Séville (1775). The prefatory headnote included by this reader reveals a lot about the purpose of this submission:

LM XIII (1782): 216. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

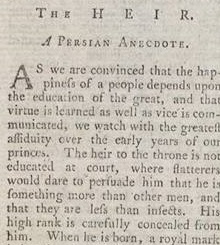

LM VI (1775): 179. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

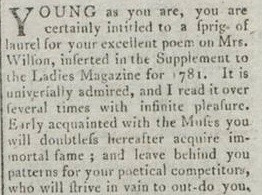

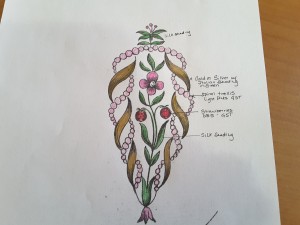

Let’s dwell on the ‘shewing’ for a moment here, and not just for its cool archaic spelling. In the earliest volumes the magazine had followed the custom of magazines to organize a monthly poetry competition on a set theme, and it seems that getting your translation into print was perceived as a similar, though less official form of distinction. In fact, this sense of achievement must have been the primary motivation for many unremunerated amateurs to contribute in the first place. For the significant number of schoolchildren who contributed, there may have been a secondary incentive, as I have suggested before. The magazine’s translation assignments will have been similar to their homework for language classes at school, and it is certainly plausible that tutors made use of the material in the magazine in their teaching, and proudly urged star pupils to submit their work as an advertisement for their schools. We usually get the most information about juvenile contributors when they furnish translations, such as in this signature appearing in April 1775 with a translation of a French item that had appeared the month before, tacitly appropriated from Pierre Bayle’s ground-breaking Dictionare Historique et Critique (1697-1702).

Although, as said above, the foreign-language originals were extracted from a variety of sources, pedagogical works (themselves usually largely consisting of extracts) come up especially often. At the time, language pedagogy consisted mainly of translation exercises, and most textbooks were mainly compilations of short French or Italian texts for translation, written in a desirable style and register that students could emulate in their own compositions. They were explicitly marketed as aids for tuition in schools, such as Peter (occasionally ‘Pierre’) Hudson’s The French scholar’s guide: or, an easy help for translating French into English, that according to Worldcat goes through 13 editions between 1755 and 1805, and holds a long list of tutors, masters and teachers of French based in Britain who endorsed the work. Extracts from it, typical light reading such as anecdotes comparing the ways of different European nations, were republished in the Lady’s Magazine. In 1785, to give another example, two fables by Aesop in Italian were published, that before had appeared in several pedagogical books dedicated to that language. Fables were a popular genre for such works, probably because they are as a rule short and are inherently didactic.

This is a good year for studying the links between translation and pedagogy in the magazine, as in 1785 one ‘J. A. Ourry’ also has a short spell of busy activity, contributing eleven items in French. Ourry was to write a book of language instruction himself, The French scholar put to trial, or, Question on the French language (1795), and, as his signature in the magazine informs us, he too was a French teacher, based at ‘Mr. Birkett’s Academy’ in Greenwich. Most of Ourry’s contributions appear to be extracts from recent numbers of the popular Parisian monthly Mercure de France, but he also undertakes an odd and seemingly original correspondence in French with a reader-contributor signed ‘Juvenis’ on a minor religious controversy, while another reader-contributor signed ‘Philomathes’ provides English translations for each letter. Assuming an affable but gently condescending tone, the teacher Ourry used the magazine to publicize his didactic skills, learning and mastery of the French language. This was a good plan, given the magazine’s inferable extensive readership among middle-class mothers.

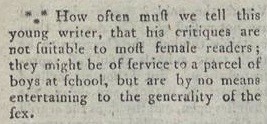

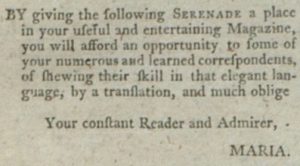

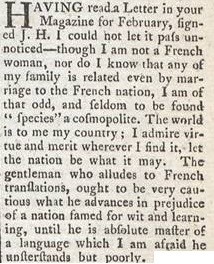

All of this demonstrates that language instruction was considered compatible with the mission of the magazine to provide content that was suitable for a wide readership of both sexes and all ages. Of course, the fact that only modern languages were included in this scheme is telling. Latin and Greek were avoided in the magazine, even to the point of removing quotes from the Classics from extracts or translating them without copying in the original, as Classical languages were usually not included in curricula for female education. When the opinionated ‘J. Hodson’ contributed a series entitled ‘The Critic’ with musings on Greek and Latin philology, an editorial note complained: ‘How often must we tell this young writer, that his critiques are not suitable to most female readers[…]?’ [LM XIV (December 1783), p. 658]. None of the French and Italian material will have given offence to even the most morally and politically orthodox readers, but they are unmistakably a means of intellectual stimulation that encouraged male and female readers to broaden their horizons. The mind of the magazine’s implied ‘lady’ reader may have been domesticized, yet she could still be a citizen of the world. In May 1789, ‘M. L. B.’ from Hillington in Norfolk replied to a letter signed ‘J. H.’ (likely the same ‘J. Hodson’) of the month before, which had denigrated a recent French translation of Milton:

LM XX (1789): 263. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This vehemence is all the more striking as there was, generally speaking, no love lost between Britain and France in this period. I wonder what the tenor of conversation was, over tea in Hillington by King’s Lynn, only two short months later.

Dr Koenraad Claes

School of English, University of Kent

[1] Shevelow, Kathryn. Women and Print Culture: The Construction of Femininity in the Early Periodical. London: Routledge, 1990.

[2] ‘domestic, adj. and n.’. OED Online. June 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/view/Entry/56663?redirectedFrom=domestic& (accessed July 17, 2016).