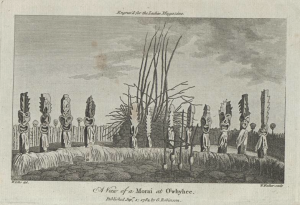

Frontispiece, LM, I (Aug 1770). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This is the blog for our major new research project on The Lady’s Magazine (1770-1818), run out of the University of Kent. The research is funded by a two-year Leverhulme Research Project grant and will result in a host of publications about the contents of and contributors to this early, long-running and groundbreaking women’s magazine, as well as a fully annotated index available online. You can read more about the project, its researchers (Dr Jennie Batchelor, Dr Jenny DiPlacidi and Dr Koenraad Claes), its objectives and its rationale here.

Over the next two years we will be using the blog to document some of our discoveries and the many challenges involved in working on so vast and miscellaneous an archive. But for our first post, we wanted to provide some essential background on a magazine that Charlotte Bronte, writing to Hartley Coleridge on 10 December 1840, declared ‘with all her heart’ she wished she had ‘been born in time to contribute to’.

LM, XV (Aug 1784). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

From its inauspicious first appearance in August 1770 to the beginning of its new series in 1818, the magazine presented its readers with a uniquely panoramic view on to the world of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life, literature and the arts and sciences. For a modest price (just sixpence for the first few decades of the magazine’s history) readers were provided with a monthly feast of short stories and serialised fiction, poetry, essays on history, science, politics and travel, advice for wives and mothers, fashion reports, recipes, medicinal ‘receipts’ offering cures for maladies from cramp to ‘hectic fevers’, accounts of trials and biographies of famous historical and contemporary figures, enigmas, rebuses and domestic and foreign news reports, as well as elegant engravings, fashion plates, embroidery patterns and song sheets.

LM, XXVI (Jan, 1805). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The concept of a periodical aimed primarily at a female readership was by no means new when the first issue appeared in 1770. John Dunton’s The Ladies’ Mercury was first published in February 1693 and in the following decades many more periodicals took up where Dunton left off, including Eliza Haywood’s Female Spectator (1744-46) and Charlotte Lennox’s Lady’s Museum (1760-61). In fact, George Robinson’s Lady’s Magazine was only the third periodical to bear the name in the eighteenth century. Jasper Goodwill’s publication of the same name had run from 1749 to 1753, while Goldsmith’s better known Lady’s enjoyed a four-year run from 1759 to 1763. Like all of these earlier works, Robinson’s Lady’s Magazine was built upon the dual premise of edification and amusement. But its generic scope and, crucially, its construction of a community of mixed-sex but largely female reader-contributors upon whom the magazine appeared to be largely dependent for the bulk of its content guaranteed its unusual success and longevity.

Frontispiece, LM, XVIII (Jan, 1787). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / [Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

In the coming weeks and months some of the fruits of our own collective (and not in the least competitive) endeavour will be posted on this blog. Please do send us any comments or questions you have about the magazine or the project.

Let me know what email address to use and I’ll send you a scan, front and back.

Hi Candice. It’s great to hear from you. Your collection sounds fabulous. It is so rare to see a monthly issue of the Lady’s Magazine with its original cover. We do have one here at Kent. In fact, it’s one of only two I have ever seen. What do the covers look like? What colour are they and do they contain book advertisements, as the others I have seen do?

Exciting project! Have bookmarked this blog to keep abreast of your findings.

I’m a collector of ladies’ magazines of the Regency period, and have several volumes of the Lady’s Magazine. My most treasured items, though, are the few magazines I have in their original covers, including the December 1790 issue of the Lady’s Magazine.

Hi Ruth. What a great project. The pages are 8 and a 1/2 by 5 and 1/8 inches. We hope this helps and would love to know how you get on with this.

What was the actual, physical size of 18th c ladies magazine? I have studies various pages from them in my book The Barbara Johnson Album &tc but I can’t tell. I wouldlike to “make one” to carry to living history events but have no idea what size it should be. Thanks very much, Ruth V. in NC