Sadly, good news stories are rare these days. So when they come along, I tend to cling to them like precious cargo that can keep me afloat amidst the torrents of awfulness threatening to pull us all under in this unsettling and violent world.

One of the best news stories of the past ten days or so is surely the restoration of a book belonging to, and filled with annotations and sketches by, the Bronte family to their Haworth home. The purchase and repatriation of the salt-water stained copy of Robert Southey’s The Remains of Henry Kirke White was made possible by a £170,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, in addition to a further £30,000 raised by a V&A Purchase Grant Fund and Friends of the National Libraries. As the BBC news website noted, this particular copy of Southey’s work was especially remarkable because of the story surrounding it. A treasured artefact of a life prematurely cut short, the book was ‘one of a few possessions saved from a shipwreck shortly before Maria married Patrick Bronte in 1812’, and bore an inscription from Patrick that read: ‘the book of my dearest wife and it was saved from the waves. So then it will always be preserved’. Preserved though it was, the book was nonetheless sold after Patrick’s death in the early 1860s and spent nearly a century in the US before its recent and happy return to Haworth. [1]

One of the best news stories of the past ten days or so is surely the restoration of a book belonging to, and filled with annotations and sketches by, the Bronte family to their Haworth home. The purchase and repatriation of the salt-water stained copy of Robert Southey’s The Remains of Henry Kirke White was made possible by a £170,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, in addition to a further £30,000 raised by a V&A Purchase Grant Fund and Friends of the National Libraries. As the BBC news website noted, this particular copy of Southey’s work was especially remarkable because of the story surrounding it. A treasured artefact of a life prematurely cut short, the book was ‘one of a few possessions saved from a shipwreck shortly before Maria married Patrick Bronte in 1812’, and bore an inscription from Patrick that read: ‘the book of my dearest wife and it was saved from the waves. So then it will always be preserved’. Preserved though it was, the book was nonetheless sold after Patrick’s death in the early 1860s and spent nearly a century in the US before its recent and happy return to Haworth. [1]

After initially reading this story on the BBC news website, I spent a good 40 minutes trawling through as many different versions of the same story as I could find. Each told more or less the same version of the same series of events in more or less the same language, as news outlets tend to do today just as they did in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. What I was fruitlessly looking for, I soon realised in my obsessive re-reading, was an answer to an unposed question: What else survived the shipwreck? [2]

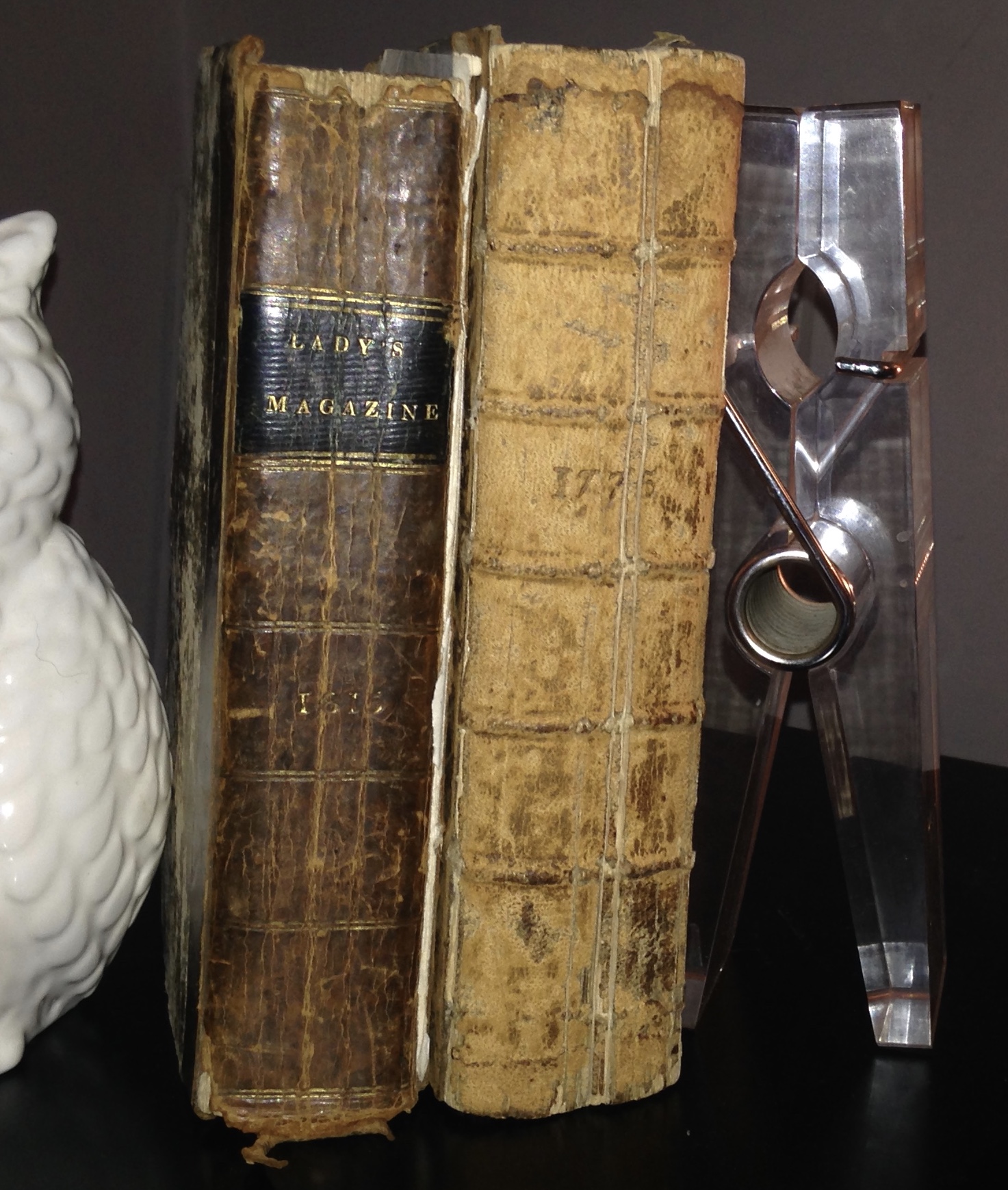

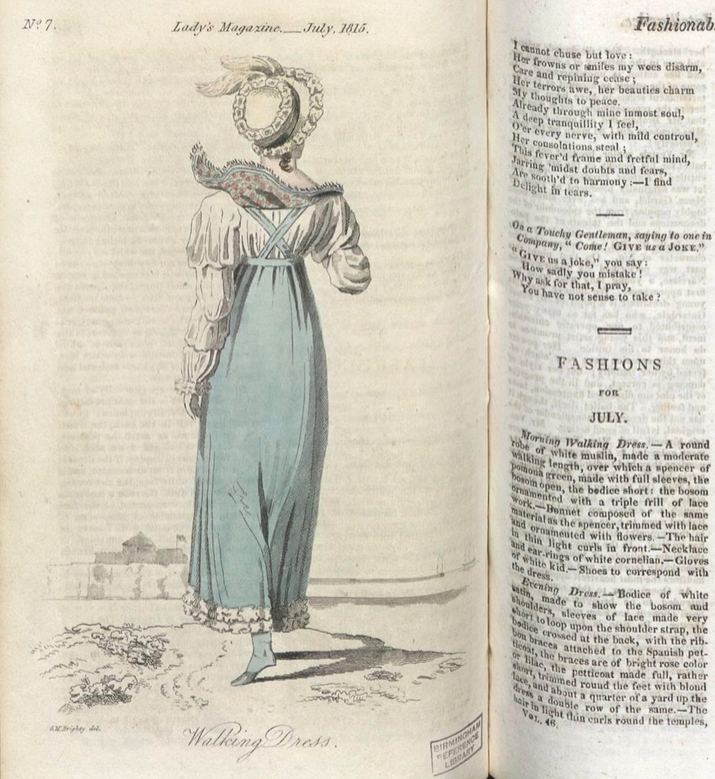

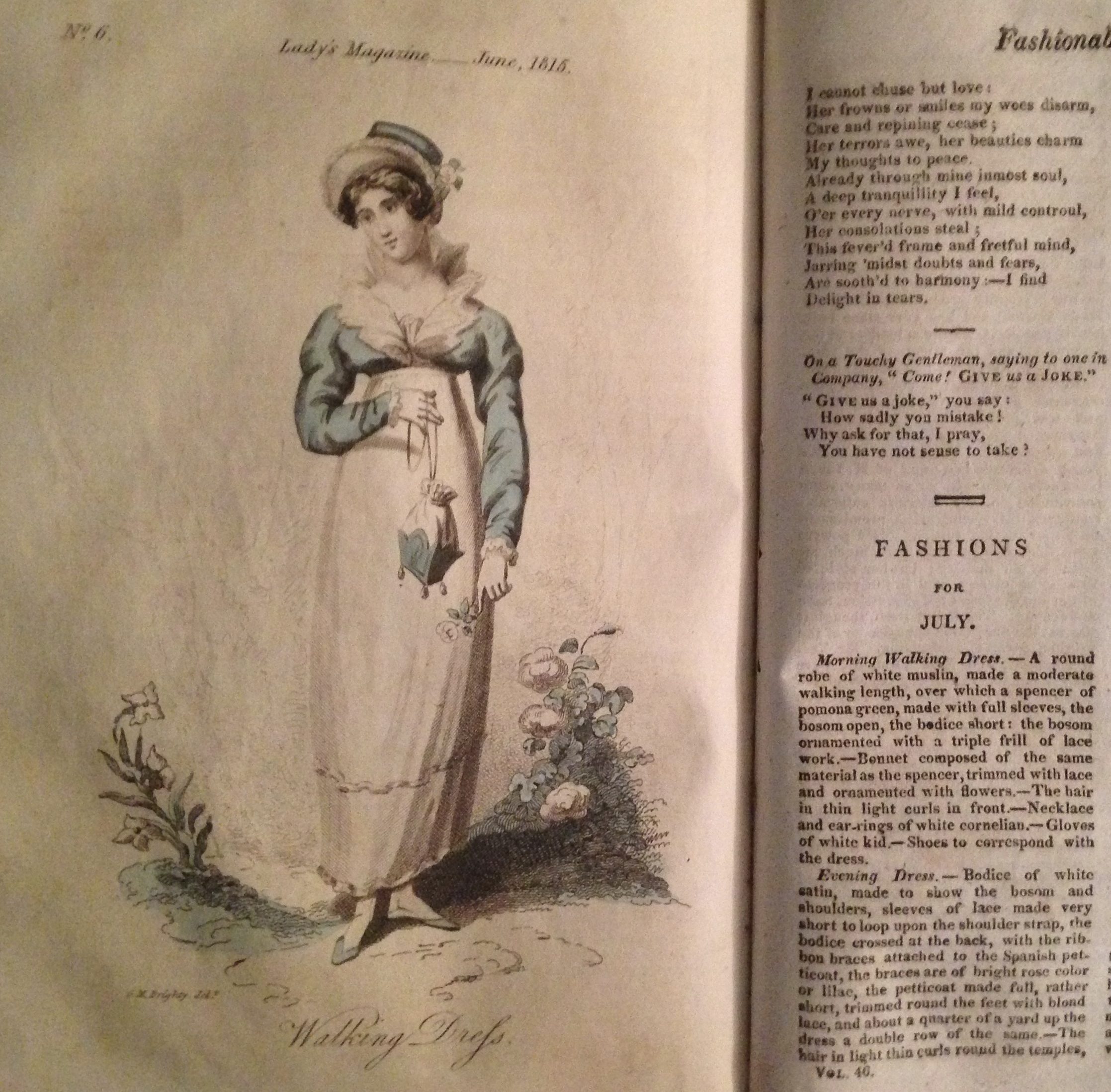

Based on the news coverage, you would be forgiven for thinking that only Southey’s Remains of Henry Kirke White was saved from the briny deep in 1812. But this was not the case. Especially prized by Charlotte Bronte was a set of volumes that kept the young woman away from her lessons and hungering after a literary career of her own: a collection of the Lady’s Magazine, the full run of which periodical extended well beyond the date of the shipwreck (from 1770 to 1832).

We don’t know exactly how many copies of the magazine Charlotte and her siblings inherited in the years after their preservation from the shipwreck, although we have some sense of which volumes survived because of the detail with which she later recalled them. Our evidence comes in the form of a letter dated 10 December 1840 to Hartley Coleridge in which Charlotte expressed regret that

I did not exist forty of fifty years ago when the Lady’s magazine was flourishing like a green bay tree—In that case I make no doubt my aspirations after literary fame would have met with due encouragement— […] and I would have contested the palm with the Authors of Derwent Priory—of the Abbey and Ethelinda. You see Sir I have read the Lady’s Magazine and know something of its contents—though I am not quite certain of the correctness of the titles I have quoted …

In fact, Bronte’s recall is accurate. Like her, I have spent many happy hours reading the anonymous gothic novel Derwent Priory (serialised 1796-97 and later attributed to Mrs A Kendall), George Moore’s Grasville Abbey (1793-97) and the unsigned ‘Athewold and Ethelinda’ (1797). The fact that Bronte remembered this fiction was remarkable because she did not have the copies before her. Although she vividly remembered the brine ‘discoloured’ pages of the magazine over which she pored ‘on holiday afternoons or by stealth when I should have been minding my lessons’, the volumes had long since left her possession by the time she wrote to Coleridge in 1840:

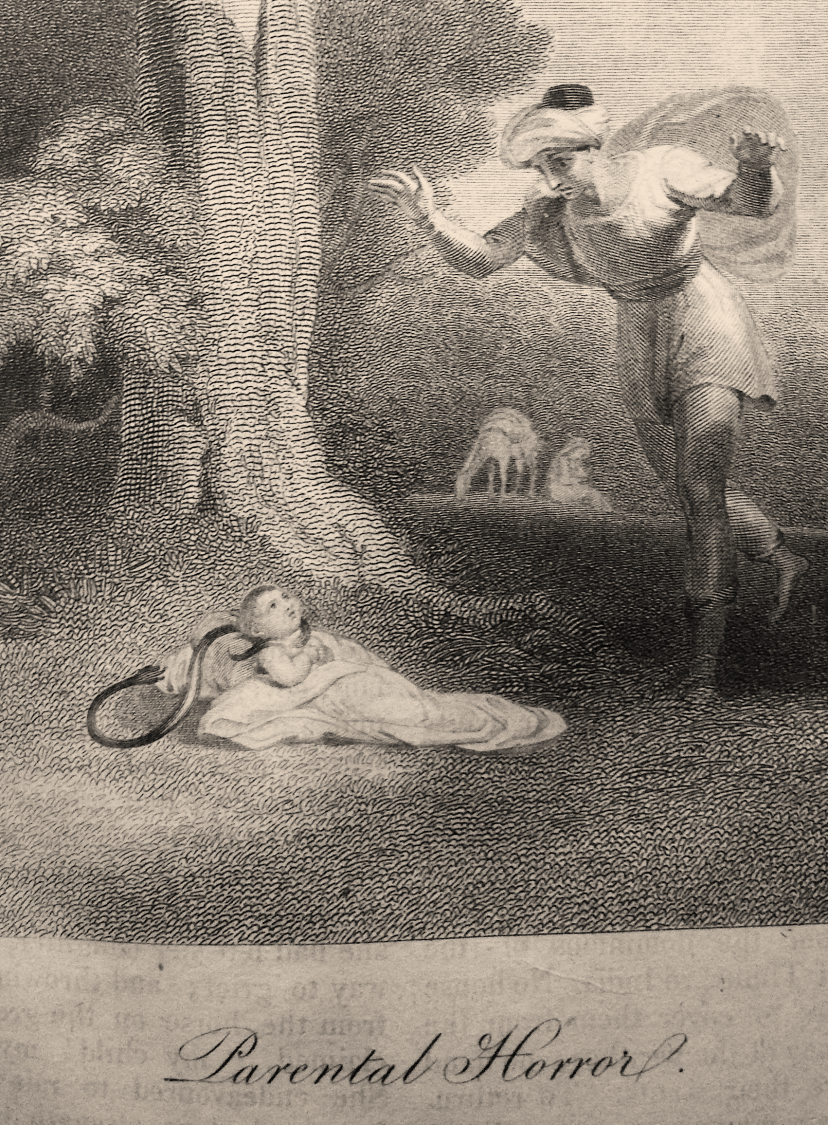

One black day my father burnt them because they contained foolish love-stories. With all my heart I wish I had been born in time to contribute to the Lady’s magazine. [3]

The sense of horror and betrayal of her father’s act was evidently very much alive to Bronte years after it had been committed and clearly ran as deep as her affection for a magazine and an associated writing culture – ‘when the Lady’s magazine was flourishing like a green bay tree’ – that she sorely lamented the loss of as an aspiring professional writer.

I refer to Bronte’s letter frequently when I talk to people about the Lady’s Magazine and I use it for lots of different reasons. For one thing, as an example of a near contemporary reader’s response to the magazine it is rare. The fact that this is an example of so well known a writer as Bronte only makes it more valuable, not least because it means that I don’t have to rely solely upon my own powers of persuasion to get people to take the magazine seriously. Don’t take my word for it that the Lady’s Magazine is interesting and was influential, here’s what Charlotte Bronte thought about it …

But of course what is most interesting about this story is the tale of survival and destruction around which it turns and the complex psychodrama it plays out. For every fact the letter seems to give us – that Bronte read the Lady’s Magazine, that she associated it with the successful promotion of women’s writing, for instance – at least one question is begged – did she really think that unpaid journalism was preferable to a life of professional authorship and did she share any of her father’s views of its foolishness, for example. Most insistently, however, the question that nags at the reader of the letter is this: How could Patrick Bronte destroy volumes that evidently meant so much to his daughter and which had been saved, along with the Southey, from the waves?

In many ways, I feel that the broader piece of research to which our current Leverhulme project is related – a book I am writing about the Lady’s Magazine‘s place in Romantic literature and culture – is an attempt to answer this question. The rage, which is at once unique to the Bronte family and yet also eerily emblematic of the fate of the Lady’s Magazine, one of the most successful women’s magazines of all times and yet all but silenced in literary history, would certainly take many more words to explain than I have in this blog post.

For now though, I am struck by something I had lost sight of until the news stories of the past week or so. The Bronte Parsonage Museum’s acquisition of Maria Bronte’s copy of what has been repeatedly described as the treasured and invaluable Remains of Henry Kirke White reminds me that what is most important and too often forgotten is that the Lady’s Magazine was valued enough to be saved. Not only that but it was valued enough by at least one of Maria Bronte’s daughters enough to be read, re-read and remembered. The story of the destruction of copies of The Lady’s Magazine by a man who likely never read it (it was far more cynical about love than foolish) should not mute the more triumphant and arguably more telling one about its survival against the odds. These volumes will never be returned to Haworth, but given the personal and, I would argue, textual legacies that the magazine undoubtedly bestowed Charlotte Bronte, they never really left there.

Notes

[1] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leeds-36844945 <accessed 28 July 2016>

[2] Prior to her marriage to Patrick Bronte, Maria sent for her possessions to be shipped from Penzance, but the vessel ran aground of the Devonshire coast en route.

[3] The Letters of Charlotte Bronte: Vol. 1, 1829-1847, ed Margaret Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 240.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent