Regular readers of this blog will know that the Lady’s Magazine project is currently running ‘The Great Lady’s Magazine Stitch Off’. We have made available 8 of the magazine’s embroidery patterns, which are being recreated, as I type, by dozens of people around the world. Many of the results will soon be on display in a major new exhibition, ‘Emma at 200: From English Village to Global Appeal’, which opens at Chawton House Library next month, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the publication of arguably Austen’s best-crafted novel.

The fact that the Lady’s Magazine has found its way into the exhibition – in a room that will be devoted to the arts of music, needlework and painting – is absolutely fitting. The magazine fed, while also being critical of, the appetite to cultivate female accomplishments in the period. It printed song sheets for much of its run as well as monthly embroidery patterns. The magazine also encouraged word play, and the kind of games that generate so much misunderstanding in Emma owe more than a small debt to the enigmas published in the Lady’s Magazine and other rival publications.

The magazine also featured and was widely read by well-known predecessors and contemporaries of Austen. The work of Stéphanie-Félicité de Genlis, a first edition of whose The Duchess of La Valliere (1804) will be exhibited at ‘Emma at 200’, was widely translated and her works serialized at length in the Lady’s Magazine. Successors of Austen read the magazine avidly, including Charlotte Brontë, whose letter on reading Emma is being loaned from Huntington library in California and will take pride of place at the exhibition.

But did Jane Austen read the Lady’s Magazine?

I wish I could say yes – my gut tells me yes – but the honest answer is we cannot be sure for now. What we do know is that the magazine was available from libraries from which the Austen family borrowed; that its fiction was circulated in the Hampshire Chronicle; and that Austen’s own novels owe some striking debts to characters and plotlines developed in the magazine’s short stories.

As Edward Copeland pointed out in his 1989 essay ‘Money Talks: Jane Austen and the Lady’s Magazine’, more than one Austen character may owe their names (and some of their traits) to short fiction in the Lady’s Magazine. Is it a coincidence that a Brandon and Willoughby both appear in Lady’s Magazine short story, ‘The Ship-Wreck’, from the Supplement for 1794? [1] Perhaps.

But as Oscar Wilde would likely not say, to find one or two literary parents in a magazine may be regarded as coincidence; to find three or four looks like proof positive.

This second piece of evidence we have is an anonymous moral tale that appeared in the November 1802 Lady’s Magazine entitled ‘Guilt Pursued by Conscience’. The story follows an alarming encounter between a young woman and ‘a man in dirty and tattered clothes, … a long beard, and naked legs and feet.’ Granted these aren’t children – the only child in this scene is the young woman’s own infant – but the parallels between this episode and that in which Harriet Smith is surprised by the gypsies in Emma are noticeable. They strike all the more forcibly because the story tells us that the young woman at the centre of ‘Guilt Pursued by Conscience’ is a ‘deserted orphan’ raised at a ‘boarding school’ (LM 33 [Nov. 1802]: 563).

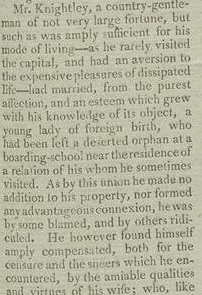

Her name is Clara, a woman of dubious origins and few prospects, who ‘despise[s] ambition’ and seeks ‘only the genuine enjoyments of domestic happiness’. These she finds in abundance with one Mr Knightley, a ‘country gentleman’ who rarely visit ‘the capital’ and who disregards the ‘sneers’ of friends by ignoring the lack of advantage in the connection and marries the young boarding school girl (563).

LM XXXIII (Nov 1802): 563. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The remainder of the story rapidly documents Clara’s history. The apparent beggar is, in fact, a wealthy former business partner of Clara’s father, who had been entrusted to make financial and pastoral provision for his friend’s charge after his death. Giving way instead to his greed and the prospects of increasing his fortune, however, he subsequently abandoned the child and when finally too troubled by his conscience to continue his life of dissipation, found himself unable to locate her, upon which unsettling discovery, he renounced his fortune to self-punish his misguided deeds. In the kind of improbably serendipitous resolution that was very familiar to Lady’s Magazine readers, this chance encounter with Clara leads to the restoration of family ties and the heroine’s fortune.

As Copeland points out, in so many ways, ‘Guilt Pursued by Conscience’ is a world apart from that of Emma’s Highbury. Indeed, Austen seems to reject outright the romance resolution that structures the ending of so many Lady’s Magazine moral tales: Harriet Smith will, after all, not marry the country gentleman. One of the lessons that Emma, especially, has to learn is that such quixotic readings of the world have no place within it and belief in them leads only to heartache.

But what are we to make of the connection between Austen’s novel and this obscure tale? Is Austen’s apparent re-writing of ‘Guilt Pursued by Conscience’ an attempt to obliterate – or overwrite, to use the term William L. Warner uses in relation to Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (1740) – the popular fiction that preceded it? [2] Perhaps.

I can’t help but feel, though, that Austen (like Richardson when writing back to the likes of Eliza Haywood) is more than a little indebted to what she might seem to criticise. Remember chapter 5 of Northanger Abbey? Austen was one of the most eloquent defenders of popular fiction of her day.

And let’s remember also that Austen wasn’t averse to deploying the improbably serendipitous ending herself. All those characters falling out of love with the wrong people and in love with right ones at exactly the right moment. All very convenient. All very ironically done. And all very Lady’s Magazine-like.

Clara Knightley and Harriet Smith have, I think, lots in common. Granted, Clara is fortuitously restored to her birthright, where Harriet doesn’t have one to be restored to, but as the moral tale and Austen’s novel make clear, neither woman needs nor wants one. Clara is perfectly happy with her Mr Knightley (who wouldn’t be?) as he is with his wife before the intervention of her putative guardian, just as Harriet is mutually happy with Robert Martin before Emma gets involved.

Both ‘Guilt Pursued by Conscience’ and Emma, I would suggest, are works of fiction that are about the improbable demands of readers for fictions of female happiness that can fall very wide of the mark. The short fiction in the Lady’s Magazine may not wear its irony as proudly or as deftly as Austen’s novels do, but it is there nonetheless, ready for Austen to learn from it.

‘Emma at 200: From English Village to Global Appeal’ runs at Chawton House from 21 March to 25 September 2016. The treasured items that will be on display for the duration of the exhibition are being loaned to the Library (a charity) free of charge, but Chawton House Library needs to raise at least £8,000 to cover transport, security and insurance costs. If you are able to make a donation online, no matter how small, please visit Chawton House Library’s website, here.

Notes:

[1] Edward Copeland, ‘Money Talks: Jane Austen and the Lady’s Magazine’, in Jane Austen’s Beginnings: The Juvenilia and Lady Susan (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989), 153-71.

[2] William B. Warner, Licensing Entertainment: The Elevation of Novel Reading in Britain, 1684-1750 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998). See chapter 5.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

t1nz3v

9ck8s3

h9t2no

8cg43w

0s2d6y

uh2qyw

6fzs37

4ifo1g

cs6vuo

re often really challenging. Gives an insight into what having French as an ‘accomplishment’ might mean!

Great post Jennie! I’ve been fascinated by The Lady’s Magazine since I looked at the translation of Genlis’s Adelaide and Theodore in it as a graduate student – another link to Emma, of course, since that’s the novel of Genlis’s that gets name-checked at the end of Austen’s novel. And the whole issue of French in the magazine is an interesting one. Those French translation and poetry ‘competitions’ are often really challenging. Gives an insight into what having French as an ‘accomplishment’ might mean!