Update: The patterns have been uploaded here for you to enjoy and try. Good luck and let us know how you get on.

Readers of this blog who also follow my Twitter feed (@jenniebatchelor) or the project’s (@ladysmagproject) will already know that this has been an exciting week for me. In the space of a week, I have purchased not one, not two, but three bound volumes of the Lady’s Magazine. I bought the first two – a bound volume for 1822 and a half-year (July to December) for 1830 – together via a conventional route which took me to a wonderful second-hand bookseller. They were a one-off and rare treat for myself, paid with by various extra-curricular work I have been doing and for which I felt I had worked hard enough to reward myself with something really pretty special. The third volume I acquired was a different story altogether.

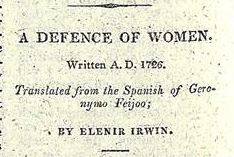

Earlier this week, I was called at work by someone whose name I had not heard before but who had heard of me via our project website and this blog. She told me that she was trying to sort through and declutter her home after a recent and nasty fall and had a lot of old books that she had bought from boot fairs, charity shops and jumble sales over the years and that she wanted rid of. One of these books was the Lady’s Magazine for 1796. She described it as tatty and said she didn’t want it any more but wanted it to find a good home, someone who would love it and look after it as she feared it might one day be put on a skip.

I asked her more about it. I asked her what page the volume started on and worked out from her answer that it was a half year that started in July. She emphasised again that the magazine’s condition was not good and I conjured a mental picture of it based on the several broken-spined, torn and heavily discoloured copies I have seen in bookshops or photographed on Ebay. Of course, I wouldn’t let it languish and would provide a good home to any copies of the magazine out there, but I concluded that this probably wasn’t a volume I would have hunted out for purchase had I not been alerted to its existence.

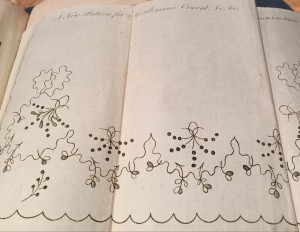

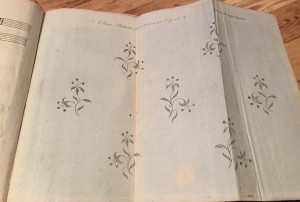

But then she told me that the magazine had some interesting stuff inside. Music. Patterns.

Patterns?

My ears pricked up. I told her a little more about the magazine and urged her not to give it away. It was of some monetary value even if very, very tatty, and because of its cultural value, I would be very interested in it and would keep it as far as possible away from that skip.

I arranged to travel to meet the book’s owner, who was an incredible and fascinating woman with whom I had so much more in common than it was possible to imagine when I first picked up the phone. We had a cup of tea and chatted about various things. She gave me cooking pears from her garden, some books for my children, and then she presented me with the magazine, which I subsequently insisted I bought from her.

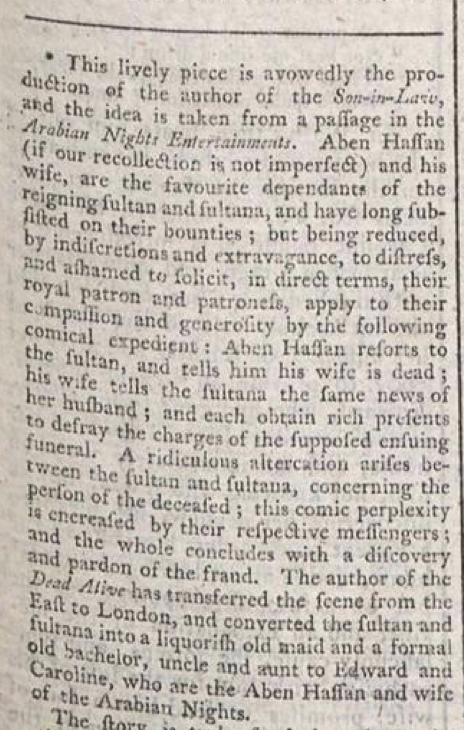

It is gorgeous! Yes, it’s mottled and discoloured in places, but the binding is in tact (half-years generally fair better than the incommodiously large annual volumes, I was reminded). But the greatest pleasure of all was finding a pattern folded behind almost every one of the fold-out song sheets the volume also contained.

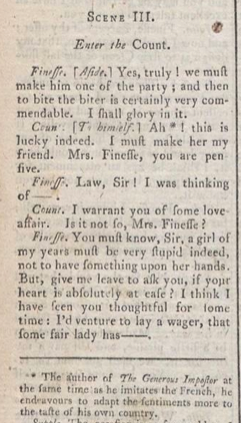

We have commented before on the blog about the expectation of the magazine’s publishers that patterns would be used and therefore ripped out of monthly issues of the periodical prior to binding in annual form. Some patterns survive in bound volumes, but the vast majority do not. We have been acquiring as many images or hard copies of these patterns as we can (if you know of or own any, please get in touch!), and I am looking forward to seeing in person a number that are in bound volumes of The Lady’s Magazine in the University of Cardiff’s Special Collections next week.

But this half-year, now my half-year for 1796, has patterns for almost every monthly issue it contains.

I was recovering at home yesterday after a minor accident, which has left me with a very sore back. I couldn’t concentrate on work, so I concentrated on the least concentration-demanding activity I could (briefly) think of: Twitter. I was so excited about my new acquisition, I wanted to show it off to other people by sharing pictures of the patterns and other engravings and song sheets. I was staggered by the reaction the images got (retweets, likes, comments, direct messages). Talk about spreading a little happiness.

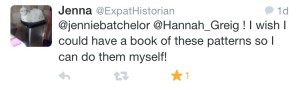

In the course of my many and fascinating interactions with people yesterday, one from the lovely @ExpatHistorian in conversation with my friend, historian and fellow eighteenth-century fashion enthusiast Dr Hannah Greig (University of York), completely stopped me in my tracks.

Wouldn’t that be great, I thought… Hang on. No: wouldn’t that be brilliant? Shouldn’t we do that? How could I make this happen? This had to happen!

As a child, my grandmother taught me to sew and I did embroidery for relaxation (and because I am hopeless at doing only one thing at a time) until my 20s. Sadly, I haven’t embroidered for nearly 20 years and, as a consequence, I am not nearly as relaxed now as I was when younger. I have often played around with the idea of one day trying out a Lady’s Magazine embroidery or tambour pattern for myself. Now might be the time to try. But how much better would it be to have lots of people doing this too? People much better at sewing than I am. What could this tell us about the patterns? About the period? About the magazine?

I don’t yet know the answers to these questions, but what I can say is that I am now confident that we are going to find out.

Thanks to the enthusiasm of our tweeps, I am going to scan all of the patterns to which I own the copyright in the next week or so and within two weeks I plan to make them available on the Lady’s Magazine project website so that people can download them and attempt to replicate them. We plan to post results and people’s experiences of trying to recreate these wonderful designs on the blog in future weeks and months.

We are completely delighted that lots of people, novices and experts with needles alike, have expressed interest in the experiment. Some will no doubt attempt to do the work in as historically authentic a way as possible. Others might feel inclined to modernise. We don’t mind. Anything goes!

All we ask is that if this does interest you, that you spread the word by sharing this post and asking people to visit our Twitter feeds where we will update you when the scans are ready.

In the coming weeks, I plan to write a little more about the context of the patterns for those who don’t know their tambours from their tambourines. But in the mean time, do let us know if you are interested in our little experiment.

Ready, set, STITCH!

UPDATE: The patterns have been uploaded now and can be found here. Enjoy and let us know how you get on!

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent