We have spent a lot of blog column inches in the past few weeks attempting to work our way through the quagmire of terms and ethical considerations that frame the culture of reprinting, repurposing, or remediating that characterises eighteenth-century magazines. The intellectual hand-wringing that has accompanied our debates about how to acknowledge unacknowledged republications of previously published material that appeared in the Lady’s Magazine in our index has resulted in a more pragmatic and, we hope, much more accurate and historically nuanced view of the legal and, more importantly, moral face of periodical publishing in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

But, as we have said before, we can’t ignore the dreaded p-word entirely, in no small part because the magazine itself did not. As promised, therefore, and in the spirit of full disclosure, I want here to turn briefly to the question of what these terms meant (and to whom they meant most) in a publication that not only made no bones about the fact that it would situate its original contributions alongside extracts from ‘the whole circle of Polite Literature’, but that also insisted that such a move undergirded its claims to public utility (‘Address to the Public’, LM XXIII [Jan 1972]: iv).

So what, according to the Lady’s Magazine is a plagiarism? Well, not, as we have documented, when it reprints something with minor amendments, reframing and no acknowledgement. No: plagiarism is not something the magazine does, it appears; it is something that happens to it.

Plagiarism, in short, is what other people do. It is not what the staff writers whom we suspect The Lady’s Magazine employed to draft its non-original content produced. It is what the magazine’s army of volunteer ‘ingenious correspondents’ who provided its original content did when lacking in ingenuity or sufficient guile to pass off others’ work as their own.

No doubt in part aware of the dangers of throwing stones in its own glasshouse, the magazine could be forgiving of such crimes and frequently registered as much in its monthly ‘To our Correspondents’ columns from which source we can glean most about the magazine’s day-to-day operations. In the April 1773 column, for instance, the editor noted that the received ‘Verses to Miss P.’, and which contained ‘a Translation of an ode of Horace’ was ‘probably a Plagiarism‘, but stopped short of recrimination beyond refusing to publish the missive. Likewise, in May 1772, the editor had reminded readers that it had ‘ever been’ its ‘endeavour to make the poetical part of our Magazine particularly pleasing’, to which end it requested with what seems like unnecessary politeness that ‘no pieces which are not originals’ be submitted to ‘that department’ (LM III [May 1772]: 226).

As these examples intimate, one of the most striking aspects of the magazine’s discussion of plagiarism is how little concerned with the practice it often seems to be. This is not to say that the editors didn’t occasionally wallow in public self-congratulation when they detected that original submissions had been fraudulently transcribed from elsewhere. When, in March 1789, the magazine divined not only that an ‘excellent’ letter from a contributor to the columnist, the Budget, who went by Clio was ‘printed Forty Years ago in the Connoisseur’, but that a ‘long Poem on Taste’ that had also been submitted was from a source that the magazine would not disclose, the editor(s) glee and superiority are not even partially masked.

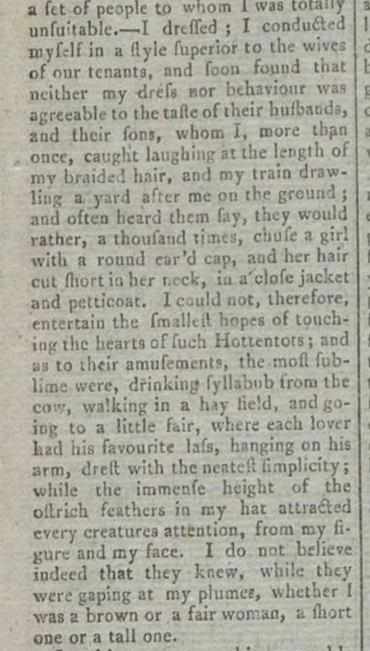

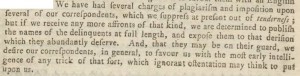

More often, however, the magazine seems principally to care (perhaps was only forced to care) about the p-word when readers did so. Take, for example, the following, printed in the ‘To our Correspondents’ column of the February 1776 issue:

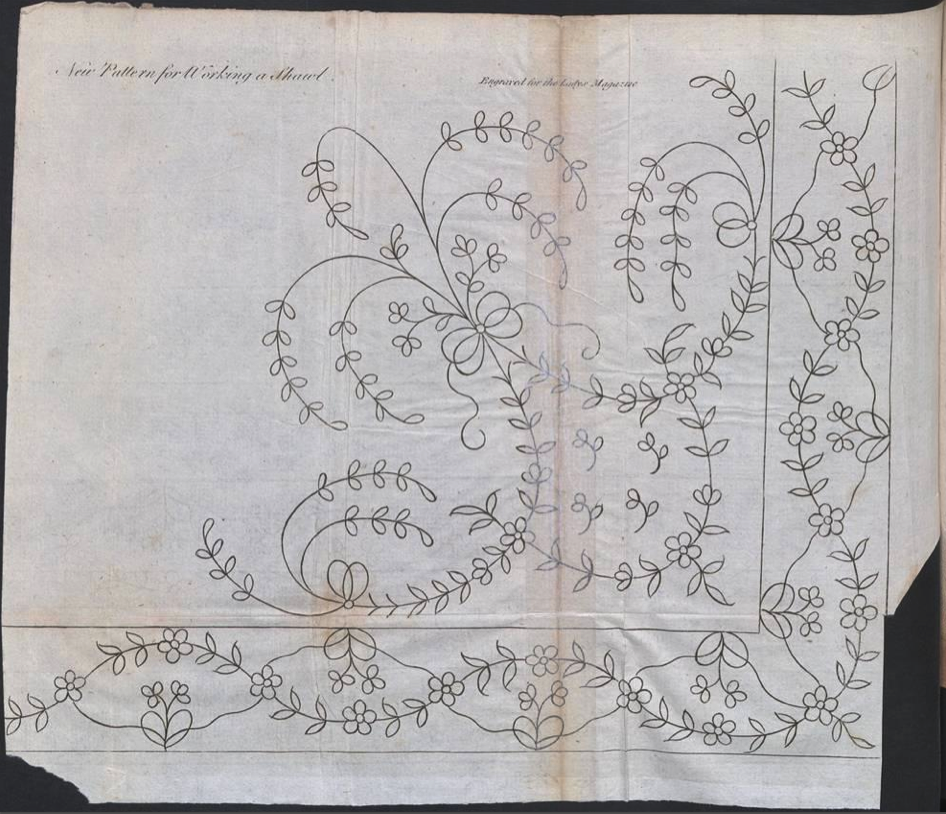

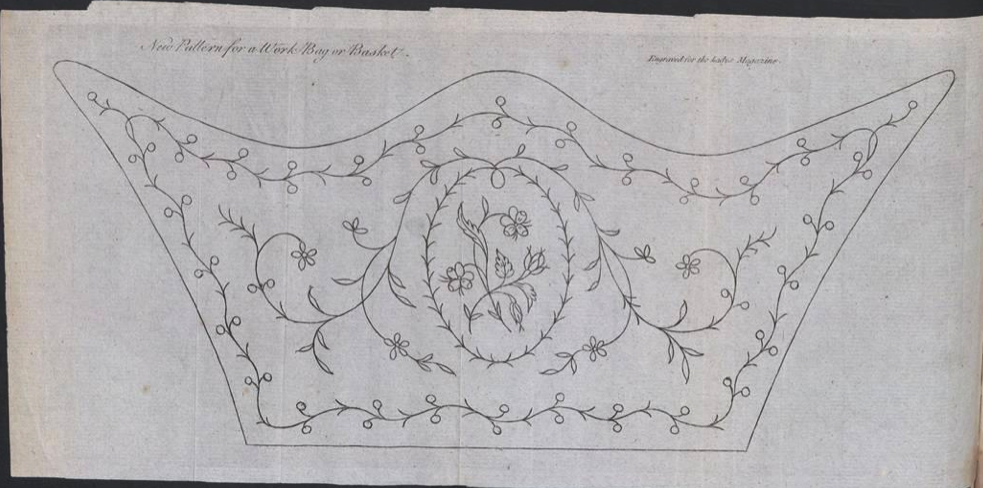

LM VII (March 1776): facing p. 116. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The blend of gallantry and threat on display here is an uneasy combination. The magazine refuses to name names or publish the full extent of the putative calumnies to which it is has been alerted. It wants to protect its authors against such imputations – to act in good faith – and sometimes went to great lengths to give contributors redress against such insinuations. When Constantia Maria, a contributor of historical essays to the magazine in the 1770s was accused of being ‘a plagiarist’ by the apparently unjustly self-righteous Justus, the magazine gave the accused, who had ‘never’, in fact, offered anything to the public as her own’ work, a right of reply (LM VIII, [July 1777]: 277) Not only that, they condemned the tactics and classiness of Justus in the ‘To our Correspondents column of the same issue: his attack on Constantia Maria is itself outed as a ‘plagiarism’ by the magazine’s editor, who pointedly declares also that he has ‘strong reasons to intimate’ that his composition – a ‘series of letters from a nobleman to his son’ is ‘not the composition of a nobleman, but a plebeian‘ (277).

Such acts of courtesy to impugned contributors extended only so long as it was mutually enforced by the behaviour of reader-contributors, however. If they failed in their part of the bargain and ‘put upon’ the magazine by trying to pass off other’s work as their own, then all bets were off, and in no uncertain terms. Such ‘literary robbers’ could be and deserved to be outed before the magazine’s readers (‘To our Correspondents’, LM [Aug 1784]).

If the magazine’s references to plagiarism smack of hypocrisy then that is in part because the stance is at least partly hypocritical, although as we have explained before, lightly edited reprintings by staff writers were a mainstay of the periodical press and seem to have considered, in modern parlance, examples of fair use . But the bigger story here, to my mind, is not why the magazine took the attitude it did towards plagiarism, but why readers seem to have taken it much more seriously than editors did. Another story again is why the act of literary plagiarism, like so many real and imagined vices of the period seems to have fallen upon women with a double weight. As a bizarre article from July 1794 notes, if the female equivalent of the male plagiarist is a woman who has lost her reputation, then a female plagiarist is surely the worst of all creatures on earth (LM XXXV [July 1794]: 352).

In none of the cases mentioned above (or any those I have come across so far) are readers who accuse other contributors of plagiarism aggrieved, as they would surely rightly be, because another has sought to pass off his or her words as their own. Indeed, even when writers did have such grounds for complaint within the periodical’s history, such as when the magazine in October 1773 famously published a song based on verses by Clara Reeve, without consulting her, the author’s complaint was not that her words had been plagiarised without her consent, but that they had not been borrowed accurately.

As Koenraad noted in his fine overview of the periodical’s position in terms of contemporary copyright law, occurs at least eighteen in the Lady’s Magazine between 1770 and 1800, and there are three of “plagiarist”‘. Even allowing for the various words used by the magazine for what we would without hesitation call plagiarisms today (articles wanting in originality, literary frauds etc), what strikes me most about these statistics is not how frequent but how infrequent these terms are in the magazine’s history. For each full year of the magazine’s run, there were 13 issues, each of about 50 to 60 pages of densely printed content. Even if we generously treble the number of references to plagiarism to encompass any and all synonyms used by the magazine, 60 references to plagiarism in well over 19000 pages of content suggests that plagiarism bleeps much more loudly on our radar than it did on that of our predecessors. Except of course, when those predecessors (like Justus) had a particular if partly inaccessible axe to grind.

So where does all this leave us? The short answer is not much further from where we began. The longer answer is not much more satisfying. The p-word was a term in widespread circulation in the period and in our periodical, as in others of the time, was registered more commonly as an ethical rather than legal matter (although the legal framework should not be forgotten). It was also a practice for which there was widespread tolerance. When W. S. wrote to the magazine in August 1784 to complain vociferously about a plagiarised letter and essay (from the Wit’s Magazine) in the Budget columns earlier in the year, the editor acknowledged the legitimacy of the discovery before noting that August 1784 issue of the Wit’s contained a novel ‘stolen’ from the Lady’s Magazine.

In the opportunistic, tit-for-tat world of the late-eighteenth-century periodical, reprintings, stolen pieces, plagiarisms (choose your own nomenclature) were everywhere. This is not to say that plagiarism doesn’t exist in or shouldn’t matter in our understanding of the Lady’s Magazine. But it is to say that the assumption that plagiarism is an intrinsically important matter without attending the complicated questions of how much it mattered, why it mattered and to whom it mattered is a least a little misguided.

To refuse to ask such questions is potentially to privilege a set of modern assumptions about the relationship between author, text and originality that we have argued numerous times on this blog have pushed periodicals like the Lady’s Magazine to the margins of literary history. Looking closely at the magazine’s vocabulary for things we think we know and describe, including plagiarism, for its contestations of arguments and concepts that we take for granted can be deeply unsettling. Nonetheless, we remain convinced that in the long term scrutiny of these issues in the magazine’s own terms and those of its time proves illuminating.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent