We have written before about some of the many difficulties involved in identifying writers published in the Lady’s Magazine. A few weeks ago I was confronted with an oddity that was a new one to me, even after working with the periodical for such a long time: two women with near identical signatures whom I was convinced were different people.

Disambiguating (to use a term Wikipedia is fond of) signatures of contributors to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century periodicals is a knotty problem. It’s very likely, for instance, that generic signatures like A. Z. or Leonora were used by multiple individuals over time or even at the same time. To complicate matters further, we also know that the signatures of a single individual could be variously presently over the course of several months or years or even in a single issue of the magazine. The prolific early nineteenth-century prose and poetic contributor James Murray Lacey, for example, went by Mr. J. M. Lacey, Esq, J. M. Lacey, J. M. L. and possibly J. M. (author of many poems in the 1800s). Internal and external evidence can help resolve these riddles, but sometimes we just can’t be sure that we can definitively link all contributions by a single author. There is also, of course, the danger that we may attribute contributions to an author on the basis of such circumstantial evidence where, in reality, their authors were two or more different people. J. M. may well be James Murray Lacey. But he may also be John Mayne, another regular poetic contributor in the same years. Or J. M. may be someone else entirely.

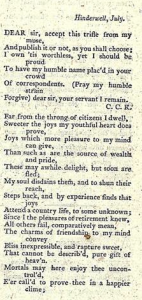

LM XLI (Aug 1810): 376. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British l Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

My own disambiguation conundrum began when reading the poetry section of the August 1810 issue of the Lady’s Magazine. Something intrigued me about the “Lines by C. C. R.”: talent; a distinctive voice. I idly wonder who s/he was (a Charles Rowley or Clara Robinson, I pondered), but setting aside my feminist concerns about essentialist assumptions for a moment, I was convinced that C. C. R. was a young woman. And then I remembered a poet whose work had appeared in the magazine a couple of years before: a Charlotte Richardson whose ‘Stanzas by Charlotte Richardson’ had been published in August 1808 and who had been addressed in a sonnet in the same year by none other than the hardworking J. M. L. Could C. C. R. of Hinderwell and Charlotte Richardson be the same person?

A cursory skim through the magazine provided some clues. C. C. R. was, indeed, a woman and, to top it all, a woman whose surname was Richardson. All was revealed in a poem entitled ‘Lines respectfully addressed to Miss C. C. Richardson, Hinderwell’ by fellow contributor Joanna Squire in the September 1811 issue (LM [Sept 1811]: 429). But I just couldn’t believe that this Charlotte Richardson and and Charlotte Richardson of the 1808 ‘Stanzas’ were one and the same. The tone and style of the poems that appeared above these signatures were too different.

I knew from a previous life of mine that Hinderwell is in North Yorkshire. So, I started googling ‘Charlotte Richardson’ and ‘Yorkshire’ and initially found several references to a Charlotte Richardson (nee Smith, 1775-1825) who had attended the Grey Coat School in York before entering service and who had developed an improbable but undeniable talent for poetry. Widowed as a young woman, with a child to feed and poverty stricken, this natural genius had been discovered and patronised by the philanthropist Catharine Cappe, who raised a subscription to have some of Charlotte Richardson’s verse published.

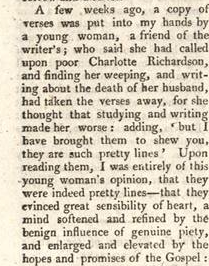

LM XLII (Oct 1811): 477. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British l Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

All this sounded very familiar. I went back to my notes on the magazine and found a biography of Richardson authored by Cappe and published in the Lady’s Magazine in September 1805 (LM [Sept 1805]: 477-79). How could I have forgotten that Cappe had written to the Lady’s Magazine alongside the Gentleman’s and a select group of other leading periodicals to help her raise subscriptions to see a volume of Richardson’s verse into the press? It duly appeared as Poems on Different Occasions in 1806.

Was Charlotte Richardson C. C. Richardson? I didn’t think so. I couldn’t find any evidence that Charlotte Richardson had a middle name at all, least of all one beginning with a C. But I found the answer I was looking for soon enough. C. C. Richardson of Hinderwell was in fact Charlotte Richardson. Just not the same Charlotte Richardson.

Charlotte Caroline Richardson (1796-1854) did live in Yorkshire, but was born in Lambeth, and led a very different life from her fellow poet. She was the daughter of Robert (died 1804) and Elizabeth Richardson (1760-1841), both of whom were poets, and had two siblings, Elizabeth (yet another poet) and Eleanor. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, Charlotte, who would become the most successful writer in her family, was sent to live with her aunt in Hinderwell, Yorkshire, as a child. In 1817 she returned to live with her long-since widowed mother, now running a school in Vauxhall. The place names that sometimes appear alongside her signatures in the Lady’s Magazine chart this move. That same year, she published Waterloo, a Poem on the Late Victory and a book of children’s verse entitled Isaac and Rebecca. Until 1818, she regularly submitted poems to the Lady’s Magazine, although none of the biographical sources I have identified mention this fact. [1] The only poem to appear under her full legal name in the magazine was ‘Hymn on the Death of her Most Gracious Majesty’ which appeared in the December 1818 issue (LM [Dec 1818]: 575). Other poetic volumes followed, as did the Robinson-published Gothic novel The Soldier’s Child, or Virtue Triumphant (1823). Four years later she married a John Richardson. A woman whose name had so perplexed me didn’t even complicate things by getting married and changing it. I couldn’t have forgiven myself if I hadn’t been able to identify her!

What interests me about the two Charlotte Richardsons is not just their writing, but the complex ways that their lives and writings are woven together in the rich if not always evenly sewn tapestry of the magazine. In a rather different way to the natural genius Charlotte Richardson, whose brutalising life story as well as sentimental verse was regaled before Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine readers, Charlotte Caroline Richardson’s life was a life lived in periodicals. Her father, a regular contributor to the long-running almanack The Ladies Diary (1704-1841), courted her mother, fellow contributor, Betty Smales, in its pages in flirtatious poetry before tracking down her location and eventually persuading her to marry him. Charlotte Caroline Richardson and her sister Elizabeth would also both publish poems in the Diary, although my initial researches suggest that none of the poems that Charlotte sent to the Lady’s Magazine were published in the Ladies’ Diary. Poetry submitted to both periodicals later appeared with other works in her Harvest, a Poem in Two Parts, With other Poetical Pieces (1818), a volume dedicated to the Ladies’ Diary‘s editor, Charles Hutton.

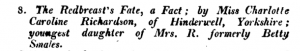

She had reason to be grateful to Hutton. For it was in his annual, in 1815, in a poem entitled ‘The Redbreast’s Fate’ about a ‘shivering’ robin caught in a storm and nurtured by the poet before being killed by a cat, that (however improbably it may sound) a reconciliation between Charlotte and her estranged mother was achieved. Perhaps it was these lines that affected Elizabeth to write back to her daughter: ‘So oft in life’s uneven way,/ Some stroke may intervene,/ Sweep all our fancied joys away/ And change the once-lov’d scene.’ [2]. In the next year’s number, Elizabeth addressed her daughter in a poem that begins by hailing her daughter’s literary talent and mourning the loss of her spouse, and Charlotte’s father, whose ‘numbers’ had ‘Long […] graved Diaria’s page’ [3]. Touched by Charlotte’s words Elizabeth vowed to ‘clasp’ her daughter to her ‘aching heart’ once again. Their reconciliation on the page as well, it seems in life, was complete.

Of course, behind these poetic effusions lay complex psychological realities that are beyond reconstruction. But what is clear is that for both Charlotte and Charlotte Caroline Richardson, life inflected their poetry and their poetry materially affected their lives, raising much needed funds or rehabilitating broken relationships. Periodicals including the Lady’s Magazine and the Ladies’ Diary were a vital technology in these processes.

Dr. Jennie Batchelor

School of English, University of Kent

Notes

[1] These sources include: Gideon Smales, EWhitby Authors and their Publications, with the Titles of all the Books Printed in Whitby (Whitby: Horne and Son, 1867), pp. 214-15;’Charlotte Caroline Richardson’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 22 July 2004, 10:55 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Caroline_Richardson> [accessed 25 August 2015 ]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Caroline_Richardson; and J. R. de J. Jackson, “Richardson, Charlotte Caroline (1796–1854)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. <http://www.oxforddnb.com.chain.kent.ac.uk/view/article/67782?docPos=2> [accessed 25 August 2015]

[2] Ladies Diary or, Woman’s Almanack, For the Year of our Lord 1815, 112: 21.

[3] Ladies Diary or, Woman’s Almanack, For the Year of our Lord 1815, 113: 20.

er…odnb Robin Jackson