I’ve started to notice a bit of a theme in our recent posts for the blog, most of which have been about the difficulty of writing them. Many of these difficulties arise from the challenge of trying to make sense of what is before us when we read the magazine. How on earth can we even begin to work out who Camilla or J. L-g was, for instance? How can we make sense of the periodical’s editorial policy when articles – sometimes articles placed right next to one another – directly contradict each other? Do such moments exhibit a lapse of editorial judgement? Or are they an accidental juxtaposition? A strategic spur to debate and controversy? Even as we start to find answers to some of these questions, more and more problems present themselves to us. It certainly keeps us on our toes, that’s for sure.

In the past few days I have been working with yet another interpretive conundrum that I have been very aware of it for some time: How can we write about parts of the magazine that are no longer there?

LM XII (Supp. 1781). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

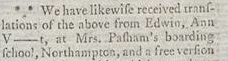

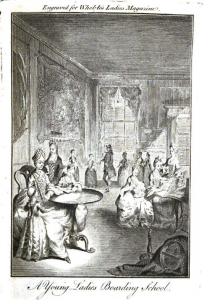

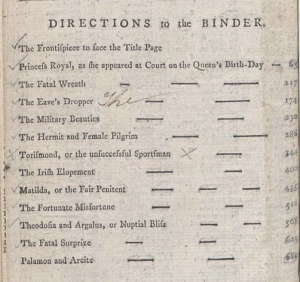

Call any magazine, especially the Lady’s, ephemera in my earshot and I’m afraid I won’t be able to let it go. The longstanding association of historical women’s magazine’s with the ephemeral, the frivolous and the disposable could not seem further from the truth behind such titles. The Lady’s was a magazine that always had an eye to futurity. Monthly issues, like those of many of its rivals, were intended to be preserved in bound annual volumes and the last issues of each year published binder’s instructions on how to organise the material for posterity, especially non-paginated items, such as the handsome illustrations the magazine provided each month. Whether you read the magazine today in digital or hard copy it will almost always be in this annual bound format for which we owe a debt of thanks to the collective efforts of binders who curated them and the readers who agreed with the magazine’s editors that the publication was worth preserving in the first place.

But not everything was preserved. Many surviving bound volumes are missing the Supplement or Index. Others are missing (whether by error or design is usually hard to tell) odd pages of text, engravings or fashion plates. (I always like to think the latter might be missing when they are because their owners had taken them to their dressmakers Barbara Johnson style, but of course, we cannot be sure.)

LM XIV (April 1783). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

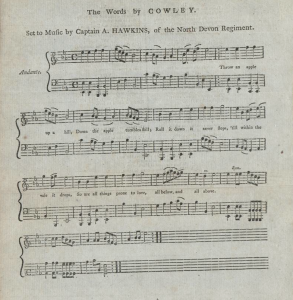

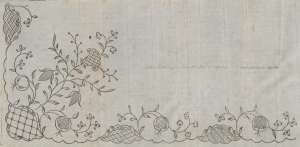

Then there are those parts of the magazine that were never designed to be preserved, not even by the editors who boasted of their inclusion. This is especially true of song sheets and embroidery patterns, both of which were regular features of the magazine in its first decades. Neither of these types of material are to be found in the annual ‘Directions to the Binder’ and in fact when they are mentioned at all, as in the note that appeared under the advertisement for the 1771 second volume, it was to confirm that they had no place in the bound versions of the magazine at all: ‘Note. The Patterns to be taken out’ (LM II [July 1771]: n. p.). Such features of the magazine were clearly meant to be pulled out and used. And evidently they were.

Nonetheless, we are fortunate that some owners and binders ignored these dictates. Indeed, song sheets can be found fairly frequently in the bound volumes of the magazine for the first two decades digitised on the Adam Matthews Eighteenth-Century Journals V database that is our main source for our project, as they are in other, less systematically digitised runs of the periodical that can be found online as well as in variously located hard copies yet to be scanned.

Embroidery patterns, however, are much less common. This has been a recurrent source of disappointment to me in the years I have been reading and working on the magazine. As I set about writing a paper I am giving at the Disseminating Dress conference at York at the end of the month, it has begun to really vex me.

LM XII (Feb. 1781). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The inclusion of a monthly pattern was an important feature of the magazine from its first issue in August 1770. In its inaugural Address to readers, the editors placed dress and fashion at the heart of the magazine’s mission and identified the inclusion of patterns as an important part of its utility and appeal to readers. The ‘subjects’ the magazine would alight upon were designed to render readers’ ‘minds not less amiable than [their] persons’, the editors declared: ‘But as external appearances are the first inlet to the treasures of the heart; and the advantages of dress, though they cannot communicate beauty, may at least make it more conspicuous, it is intended in this collection to present the sex with the most elegant patterns for the Tambour, Embroidery, or every kind of Needlework.’ Taking advantage of ‘the progressive improvement made in the art of pattern-drawing’, the magazine could boast for just sixpence an issue for the first three decades of its run: ‘[e]very branch of literature’, ‘engravings designed to adorn the person’, as well as ‘a pattern’ that alone ‘would cost them double the money at the Haberdashers’ (LM I, [Aug. 1770]: 1).

In part this is a masterpiece of marketing, the eighteenth-century equivalent to a television shopping channel telling you that not only will the advertised purchase price get you X and the Y you never even knew you wanted, but a free (yes: absolutely free!) Z into the bargain. But my strong feeling is that the patterns represented much more than simply a commercial ploy.

Patterns served various ends within the magazine. Some were educational. I think I would feel as if all my birthdays and Christmases had come at once if I ever came across one of the patterns for embroidered maps of Britain and the Americas published in 1776 and 1777 and intended to supplement the fascinating series of essays on the history and geography of these nations published in these years. I haven’t seen any in copies of the magazine I have consulted.

LM XVII (Mar. 1786). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The vast majority, though, were for decorating garments and other household objects, from watch cases and fire screens to sleeves, pockets and gentleman’s ruffs. These patterns can potentially tell us a great deal about the magazine and its understanding of its female readers. At the very least, their inclusion is a strong indication that for all its interest in the elaborate and extravagant fashions worn at court and by contemporary celebrities such as Mary Robinson or Sarah Siddons, the Lady’s expected its middling readers (lady does not mean aristocratic, here) to fashion themselves in a modest and simple style. Ornamentation, in all things, merely for ornamentation’s sake was to be despised. In both their intellectual and sartorial pursuits, the magazine’s readers were instead supposed to be characterised by a considered elegance, marked by grace and cultivated through reflection and practice. I strongly suspect that the embroidery patterns the magazine published played an important part in shaping this ideal.

LM XII (Supp. 1781). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Every single one of the patterns that appeared in the magazine is briefly described in the table of contents for the month in which it appeared. Quite what the existence of more of the physical patterns would add to this picture is uncertain. What is clearer to me is that their absence is not a sign that the magazine was frivolous or disposable. In matters sartorial as in all things, the Lady’s saw itself as both attractive and useful to the lives of its readers. The fact that so few of these patterns have survived to this day – that many were presumably used – suggests that it may well have been right.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent