I often find that notation gets in the way of music. Granted, it’s an evolved communicative system that works to impart information from composer to performer, but sometimes it actually runs slightly counter to what the music actually feels as though it wants to do.

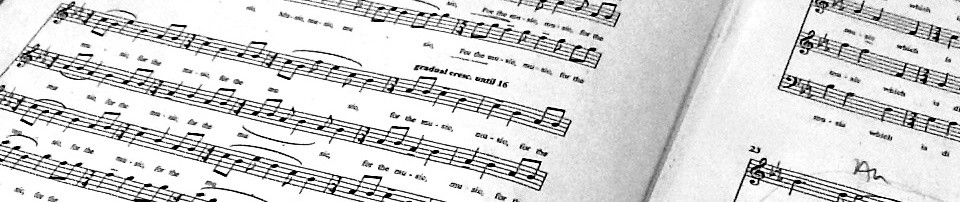

This has become particularly apparent in recent rehearsals as the Chamber Choir works on Lassus’ Chi Chi Li Chi, a cacophony of bantam-banter in a late sixteenth-century chicken-shed, written well before the modern standard system of notation. Stepping deftly between different metres, full of rhythmic interplay, the notation actually works against the sense of flexibility and vitality which lurks at the heart of this outrageous piece. We’ve had to re-bar certain sections and write different stresses into the scores, in order to overcome the tyranny of regularity imposed by barlines.

This has become particularly apparent in recent rehearsals as the Chamber Choir works on Lassus’ Chi Chi Li Chi, a cacophony of bantam-banter in a late sixteenth-century chicken-shed, written well before the modern standard system of notation. Stepping deftly between different metres, full of rhythmic interplay, the notation actually works against the sense of flexibility and vitality which lurks at the heart of this outrageous piece. We’ve had to re-bar certain sections and write different stresses into the scores, in order to overcome the tyranny of regularity imposed by barlines.

It’s hard; as musicians, we’re so well-trained to observe bar-lines and time-signatures in our subservience to the printed score that we can find it difficult to ignore them, in order to allow the natural rhythmic language of a piece to come through. But, as I keep reminding the singers, notation is only a means to an end: the music lives not on the printed page, but in the moment of delivery, in the white-heat of off-the-page performance. Lots of work still to do, but it seems to be working. (Well, I’ll let you know after our all-day rehearsal this Saturday…).