A miserable night yesterday: dark, windy, cold and raining.

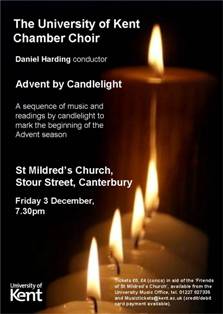

Inside St. Mildred’s Church, however, light, music and jollity abounded; we had battled the elements in order to hold our customary Tuesday night rehearsal in the church, in order to work without a piano and to get a sense of the space and the acoustics for the concert.

Inside St. Mildred’s Church, however, light, music and jollity abounded; we had battled the elements in order to hold our customary Tuesday night rehearsal in the church, in order to work without a piano and to get a sense of the space and the acoustics for the concert.

The antiphons are developing: a little more confidence in delivery is needed here; singing plainchant is a skill that requires initial groundwork, and many have not sung this style of music before; a combination of flexibility in the line, following the rise and fall of the speech, as well as confidence in taking responsibility for the line and doing so at the same time as everyone else. Tricky – it requires a lot of work to appear effortless!

The carols are progressing, too; singing in the acoustic of the church meant we could really start to draw forth a full ensemble sound from the group, balance the parts, and begin to explore bringing out specific notes and phrases in particular voices. Bethlehem Down especially is starting to develop some three-dimensionality as it lifts off the page, and with some sensitive dynamics starting to be included, it’s going to be a treat.

The final singing of the evening was a chance to re-visit Skempton’s He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven. It’s not a Christmas piece, it’s not in the Advent service in a few weeks’ time – in fact, we’re not actually singing it until February. But this was too good an opportunity to miss: the chance to sing it in a sonorous acoustic, arranged in a crescent-shape similar to the way we’ll be standing to perform in the Cathedral Crypt. (And besides, I love the piece, so any opportunity to sing it is welcome indeed…). We took it a fraction under-tempo, as it’s been several weeks since we first sang it, and this is only the second reading; this meant the chords hung in the air for just a little longer than usual, and the colours really had a chance to blossom. It worked so well, in fact, that I’m wondering whether it shouldn’t go at that speed in performance; it’s marked Andante, but perhaps my enthusiasm has pushed the speed slightly ? Something to think about…

The final singing of the evening was a chance to re-visit Skempton’s He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven. It’s not a Christmas piece, it’s not in the Advent service in a few weeks’ time – in fact, we’re not actually singing it until February. But this was too good an opportunity to miss: the chance to sing it in a sonorous acoustic, arranged in a crescent-shape similar to the way we’ll be standing to perform in the Cathedral Crypt. (And besides, I love the piece, so any opportunity to sing it is welcome indeed…). We took it a fraction under-tempo, as it’s been several weeks since we first sang it, and this is only the second reading; this meant the chords hung in the air for just a little longer than usual, and the colours really had a chance to blossom. It worked so well, in fact, that I’m wondering whether it shouldn’t go at that speed in performance; it’s marked Andante, but perhaps my enthusiasm has pushed the speed slightly ? Something to think about…

(Don’t tell the composer…).

The anthologies having arrived, this week was the chance to get in a festive mood by working on the carols for the Advent service looming around the corner. To start, Ding, dong merrily on high! and the opportunity to work on sustaining the long phrases on ‘Gloria,’ and to get the bell-sounds pinging off the page – as with the Vaughan Williams ‘Full fathom five,’ there needs to be a really percussive ‘d’ to the ‘ding’ and bright vowel-shapes to get the notes crisp and vibrant, rather than heavy and dragging.

The anthologies having arrived, this week was the chance to get in a festive mood by working on the carols for the Advent service looming around the corner. To start, Ding, dong merrily on high! and the opportunity to work on sustaining the long phrases on ‘Gloria,’ and to get the bell-sounds pinging off the page – as with the Vaughan Williams ‘Full fathom five,’ there needs to be a really percussive ‘d’ to the ‘ding’ and bright vowel-shapes to get the notes crisp and vibrant, rather than heavy and dragging.