Bravo.

Images courtesy of Mick Norman.

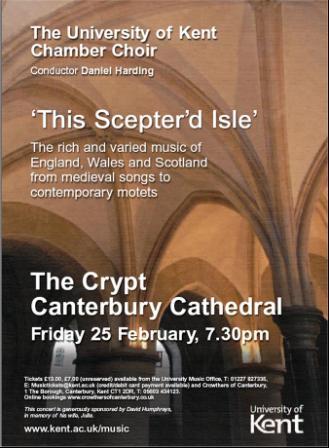

That’s it! The final two rehearsals this week are over, and arrangements are in place for tomorrow’s Crypt Concert.

Since last Tuesday, all the rehearsals have been without a piano; and we’ve found we no longer need it. This is a tremendous boost for the group. And now, after the unkind and spartan acoustics of the lecture theatre and OTE rooms in which we’re used to rehearsing, the next time the group invokes a chord, it will be in the richly reverberant acoustics of the Crypt. After all the hard work, it will be a fine reward: we just have to make sure we’re not overwhelmed by the sound, and forget all the discipline and the nuances we’ve worked to achieve.

The challenge with rehearsing and performing in the Crypt on the day of the concert, for the conductor at least, is to pace the pieces – and the programme as a whole – to take account of the tremendous sonic possibilities offered by the Crypt. We get a short time to sing through the pieces in the afternoon, before the performance in the evening, and very quickly both conductor and choir have to adapt to the new acoustic, to allow sufficient time for chords to die away and to pace phrases so that words and quicker passages of notes aren’t lost.

It’s a very steep learning curve on the day: but we’re ready for it. Here we go…

With only a week to go before the Crypt Concert, the Chamber Choir are starting to hit their stride. It’s interesting how, on two consecutive days, you can have to completely contrasting rehearsals. Tuesday night was hard work – the end of a long day for many of the students – and the Jackson and Macmillan are difficult pieces.

A second rehearsal on the following Wednesday, however, was a really tonic; gathered in the round in the old OTE rehearsal room, we had our first complete rehearsal without any piano accompaniment, and worked on all the pieces we’ve (I’ve ?!) neglected whilst concentrating on the more challenging repertoire.

A second rehearsal on the following Wednesday, however, was a really tonic; gathered in the round in the old OTE rehearsal room, we had our first complete rehearsal without any piano accompaniment, and worked on all the pieces we’ve (I’ve ?!) neglected whilst concentrating on the more challenging repertoire.

And what a fillip it was: everyone came out of the rehearsal on a real high; flying completely solo, with no piano-safety-net, confirmed that we’re nearing our best.

The final rehearsals loom this week: with the impetus of Wednesday behind us, they should fly by. We’ve actually started to become excited about the concert now, a sure sign that we’re becoming more confident in the music, and can start thinking about really performing the pieces rather than simply singing them through.

Roll on Friday!

Nearly all the altos...

A long and hard-worked choral week, last week. With less than two weeks to go until the Chamber Choir’s Crypt Concert, we had a longer than usual rehearsal on Tuesday night, and the choir also had their second workshop day on Saturday. The Cecilian Choir suffered a blight of illnesses and looming course deadlines to be rather decimated at their Thursday session, which meant the planned rehearsal of looking at new repertoire had to be shelved: with so many members missing, it’s not worth looking at new pieces, better to wait until the group is near to capacity.

Saturday was a very long day, but an extremely useful one. Looking at the more difficult pieces in greater detail makes for long and tiring rehearsal periods, so the more challenging pieces were alternated with less difficult works, in order to provide some respite from part-by-part note-bashing and building pieces in sections. Credit to the choir: we covered eight pieces in the entire day, which is a very good work-rate indeed. And that doesn’t even include the warm-up piece, a brief arrangement I’ve made of Rusted Root’s Send Me On My Way, familiar these days as part of the soundtrack to the animated film, Ice Age.

The state of the tenor

With the concert date so close, I am playing even less closed-score accompaniments to the pieces, to get the choir used to singing without the support of the piano beneath them; throwing in the odd bar to check intonation or highlight an important part is really all I want to be doing at this stage. Some of the more difficult pieces needed more than this, but we all felt we’d achieved greater confidence with some of the works, especially the Tippett Gwenllian which offers no vertical logic at all; the voice-parts only really come together in the final three bars.

Bass desires...

We took several of the pieces out of the rehearsal room and into the foyer of the building itself; the lecture theatre in which we rehearse offers little supportive resonance, and I wanted the group to be able to sing in an acoustic with a little more reverberation; the foyer, whilst no church nave, is still a marked improvement over the lecture room. Suddenly, you could hear a little bloom around the colours of the Macmillan; as one of the basses remarked, “Gosh, it’s nice to hear the other voices for a change!” Rehearsing in tiered rows is great for visibility, but makes it difficult for the singers to hear other voice-parts.

The Sopranos...

So, a long week. Work still to do, but things are starting to come off the page really well; the English madrigals are virtually leaping out of the score, and the rich harmonies of the Jackson Edinburgh Mass are starting to become more secure. The clock is ticking…

As a companion and a contrast to the Saint-Saens setting of the Ave Verum Corpus, the Cecilian Choir today began rehearsing Mozart’s setting of the same text. Two very different treatments of the text: Saint-Saëns’ quite straightforward response to the words, Mozart’s much more lyrical and impassioned. I find programming two contrasting settings of a piece of text to be a interesting feature of concert-planning; each throws up facets of the other that listeners might not have otherwise noticed, or be able to compare a setting they might already know with one they’ve not heard before.

As a companion and a contrast to the Saint-Saens setting of the Ave Verum Corpus, the Cecilian Choir today began rehearsing Mozart’s setting of the same text. Two very different treatments of the text: Saint-Saëns’ quite straightforward response to the words, Mozart’s much more lyrical and impassioned. I find programming two contrasting settings of a piece of text to be a interesting feature of concert-planning; each throws up facets of the other that listeners might not have otherwise noticed, or be able to compare a setting they might already know with one they’ve not heard before.

We gathered in the round – Circle Time! – to sing the Saint-Saëns, and also to re-visit the plainchant ‘Ubi Caritas’ and Duruflé’s setting from last week. We took the plainchant more slowly than we have done before; I find that slowing pieces down just a little opens up a conversely larger amount of space in music – there’s time to really feel the phrases finish, to let the notes die away in a resonant acoustic before moving on. Getting the choir to stand in a circle really makes for a rich sound; suddenly, people can hear and relate to other voice-parts moving that they hadn’t previously really been aware of; they also feel more a part of the collective whole, rather than standing strung out in two lines as we are when we are seated in rehearsal.

We gathered in the round – Circle Time! – to sing the Saint-Saëns, and also to re-visit the plainchant ‘Ubi Caritas’ and Duruflé’s setting from last week. We took the plainchant more slowly than we have done before; I find that slowing pieces down just a little opens up a conversely larger amount of space in music – there’s time to really feel the phrases finish, to let the notes die away in a resonant acoustic before moving on. Getting the choir to stand in a circle really makes for a rich sound; suddenly, people can hear and relate to other voice-parts moving that they hadn’t previously really been aware of; they also feel more a part of the collective whole, rather than standing strung out in two lines as we are when we are seated in rehearsal.

We’ve now got so much sheet music that we’ve had to resort to folders for everyone to be able to keep all their music together: a sure sign that the choir are able to work swiftly through repertoire and a tribute to the ease with which they pick new pieces up quickly; good news, indeed!

You’d have thought persuading the gentlemen of the choir to sing in a lusty and bawdy fashion would be no problem. The opening of the setting of Mother, Make My Bed which I’ve written for the concert starts with a rambunctious repeated pattern for the tenors and basses, which needs to be delivered in not quite a thigh-slapping manner, but not far off. And yet…they were terribly polite and mannered about it; it was far too refined. More loose living before next week, chaps, maybe ?!

Finzi finesse

It was back to England this week, after last week’s rehearsal of Scottish pieces, and a chance to dance with Finzi’s My Spirit Sang All Day. This piece is a complete joy, full of life and bursting with sheer delight in its harmonic revelry. It’s also the last new piece to prepare for the end of the month (apart from the encore, should we need one, which is a popular favourite that we can learn at the drop of a hat nearer the time); from now on, it’s all consolidation, which makes me feel an awful lot better!

Whenever I start to become nervous about the concert – it’s a big programme, with challenging works, in an awe-inspiring venue – I should just get the choir to sing the Skempton Cloths of Heaven, and all shall be well. We looked at if for the third time last night (that spreadsheet I wrote about keeping earlier is really starting to pay dividends – I can see which pieces we’ve neglected in a trice!), concentrating now on balancing the chords and making sure all the lovely semitone clashes between the inner voices are brought out, or making the sure the basses’ sustained pedal notes can be heard. The basses are, at several points, the driving force behind the emotional impact of the piece; they either underpin the gently breathing harmonies with a solid pedal-note, or at crucial points rise up over an octave to really push the texture upwards.

Although I’m endeavouring now to try and provide as little support on the piano as possible, to get the choir accustomed to singing without any accompaniment, there’s a danger that the pitch can drop and you can end up a good semi-tone lower at the finish, something we’ll have to work on improving.

We revisited the Vaughan Williams songs to finish the rehearsal, endeavouring to impart a sense of rhythmic vitality into the sprightly ‘Over hill, over dale,’ whilst contrastingly making sure the bell-like effects of ‘Full fathom five’ were working. The chords struck in the four-part divisi sopranos throughout the opening section need to begin percussively with a crisp ‘d’ on the words ‘ding’ and ‘dong.’ The altos really showed themselves to be solid masters of the beat, holding the straight crotchet beats against the triplet rhythms in the other voices: I’m beating with one hand in six and with the other in four, so it’s certainly a piece to keep everyone on their toes, including me…

(Preview tracks via LastFM).

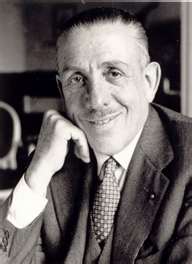

The Cecilian Choir reached the French stage of their concert programme this week, with motets by Duruflé and Poulenc. Duruflé’s achingly beautiful Ubi Caritas et Amor is part of a set of four motets using Gregorian themes, clothing pieces of plainchant with wonderfully rich colours.

As part of the programme, we will be singing the piece of plainchant itself separately, followed by the motet; the intention is to telescope the medieval and modern, juxtaposing the ancient modal chant with the modern exoticism of Duruflé’s setting. We began the rehearsal with the plainchant, learning to follow the natural rise and fall of the phrases and leave a measure of flexibility in singing through the lines.

Duruflé gives the plainchant melody to the altos at the start of Ubi Caritas, so the alto section were grateful for having learnt their line already when we came to learn the motet. There are some lovely cluster-chords in the piece; the plainsong grounds the tonality firmly in Eb, whilst the accompanying sonorities clothe it with all manner of jazz-indebted, added-note harmonies. We were short of several people this afternoon – the Housing Fair had students flocking to it in order to organise their accommodation for next year – but the choir still managed to bring out most of the colour. The tenors and basses were underpowered, though: talking to some of the group afterwards, most of the sopranos had already arranged their accommodation: are women more organised and efficient than men, perchance ?!

Using my trick of learning new pieces backwards that I’ve talked about before, we started halfway through Poulenc’s Exultate Deo, which we’d briefly started last term. It’s jolly hard: Poulenc’s trick of swinging through adjacent or parallel harmonies that are not necessarily related to each other makes for some angular lines in the voices; quite often, the altos and sopranos are having to leap over augmented fourths or fifths, and the score includes a fistful of double-sharps or enharmonic changes that mean what appears to be two different notes are actually the same one. We learned a section carefully, practicing moving between difficult chords to make sure the voices knew where they were going.

Using my trick of learning new pieces backwards that I’ve talked about before, we started halfway through Poulenc’s Exultate Deo, which we’d briefly started last term. It’s jolly hard: Poulenc’s trick of swinging through adjacent or parallel harmonies that are not necessarily related to each other makes for some angular lines in the voices; quite often, the altos and sopranos are having to leap over augmented fourths or fifths, and the score includes a fistful of double-sharps or enharmonic changes that mean what appears to be two different notes are actually the same one. We learned a section carefully, practicing moving between difficult chords to make sure the voices knew where they were going.

With a great deal of slow note-bashing and difficult lines to sing, one could sense morale dropping slightly; working backwards in two-page sections made life somewhat easier, as we covered passages more familiar from last term. Recapping previously-sung sections and singing into and through the new passages meant the piece gradually began to come together: there was definitely a sense of ‘Ah, I recognise this bit from last term!’ followed by ‘Ah, now I’m starting to recognise the new bit as well!’ which meant dipping spirits began to rally.

We ended by singing through Ubi Caritas once more, in order to reassure ourselves that we had learned something well enough at this rehearsal, and to lift morale – “We can DO this!” I’ve altered the planning of rehearsals this term – we’ll be looking at chunks of the Poulenc each week, along with the other repertoire to learn, and be working on it as more of a long-term piece. But parts of it are already starting to sound excellent, and I’m sure we’ll get there. It’s such a great piece, it will be worth it…

And just to demonstrate what we’re working towards, here’s the choir of Kings’ College, Cambridge, singing the Duruflé (with what appears to be a young David Tennant in the alto section…). The singing, like the piece, is exquisite.

(Preview extracts via LastFM).

It was going to be a challenging rehearsal, I thought: two pieces by Scottish composer James Macmillan, the canonic Gallant Weaver and heart-rending A Child’s Prayer, and the ‘Gloria’ from Gabriel Jackson’s Edinburgh Mass. These are difficult pieces – hard enough to realise at the piano when there’s no closed-score piano reduction to aid rehearsing! – with complicated rhythmic interplay, angular lines that aren’t necessarily leading where you might expect them to go, and modern harmonies rich in added-note chords and eight-part vertical sonorities. I expected it to be something of a difficult rehearsal.

It just shows how wrong one can be.

Having kicked off in lively fashion with Perspice Christicola, better known as Sumer is icumen in but with a sacred Latin text, to get everyone warmed up, we sojourned north of Hadrian’s Wall with Macmillan’s A Child’s Prayer. This has been a favourite piece of mine for a while – it’s one of those pieces that, at first hearing, reaches straight into your soul. We built the three main chords from the basses upwards to get them balanced and in tune, and practiced moving from one chord to the next to make sure the singers knew where they were going. And then – we sang them as written. It’s one thing to know and love a piece that you’ve listened to many times, but to be in the midst of the sound the first time it comes off the page and into the air is a thrilling moment. We then added the two (patient!) solo sopranos, and set off through the whole piece. In the rich and resonant acoustic of the Cathedral Crypt, it will be overwhelming…

Having kicked off in lively fashion with Perspice Christicola, better known as Sumer is icumen in but with a sacred Latin text, to get everyone warmed up, we sojourned north of Hadrian’s Wall with Macmillan’s A Child’s Prayer. This has been a favourite piece of mine for a while – it’s one of those pieces that, at first hearing, reaches straight into your soul. We built the three main chords from the basses upwards to get them balanced and in tune, and practiced moving from one chord to the next to make sure the singers knew where they were going. And then – we sang them as written. It’s one thing to know and love a piece that you’ve listened to many times, but to be in the midst of the sound the first time it comes off the page and into the air is a thrilling moment. We then added the two (patient!) solo sopranos, and set off through the whole piece. In the rich and resonant acoustic of the Cathedral Crypt, it will be overwhelming…

Macmillan’s Gallant Weaver is a richly polyphonic treatment of a Scottish folk-song, with a three-part canon in the sopranos – no closed-score, what a challenge to play! – literally weaving the melody amongst the divided upper voices; the lower three voices provide gently lulling sustained chords beneath, before the whole choir burst out into individual part-writing for a sumptuous second verse. It’s certainly difficult, the sopranos having to have the confidence to sustain their own lines against not only the same melody in canon but the colourful harmonies beneath. And it worked very well.

The Jackson Gloria represents the greatest rhythmic difficulty in the entire programme; leaping between 5/8, 3/8 and 2/4 or ¾ bars is taxing; added to which are the tumbling lines in the sopranos and altos like bells pealing, and the fact that the tenors and basses move at different times to both soprano and alto lines. We’re two-thirds of the way through the movement; there’s still work to do, but the effort will be worth it if we can capture the luminous colour and brightly-lit harmonies of the piece as it comes off the page.

Some hard work last night, and some excellent results; quicker than I thought possible. Here’s hoping it continues over the coming weeks; with only five rehearsals left before the concert, we can’t afford to waste a single moment.

(Preview clip via LastFM).

A series looking at the art of the choral conductor.

It’s important, in rehearsals, to move the choir around. Too often, voice-parts grow accustomed to hearing the same singers around them each week which, if it’s their own voice-part, can lead to a great sense of security and, sometimes, a reliance on that other singer.

It’s important, in rehearsals, to move the choir around. Too often, voice-parts grow accustomed to hearing the same singers around them each week which, if it’s their own voice-part, can lead to a great sense of security and, sometimes, a reliance on that other singer.

Moving the singers around in practice sessions means they hear a different voice-part singing next to them; breaking up the group, such that they stand in a circle but aren’t standing next to someone who is singing the same part as they are, means they suddenly don’t have the comfort-blanket of being surrounded by others singing the same line. Not only do they have to work a bit more to keep their own line, but they can suddenly hear another line next to them, and can start to hear how their line moves in relation to another. (It’s also a great way of showing singers who don’t quite know their line that they need to learn their music, without pointing fingers at individuals…!).

Socially, too, it’s a useful tool to deploy: people suddenly have to stand and sing next to others whom they might not know so well, and it’s a great way of getting them working with others.

Arranging the choir in a circle, rather than in lines, means that the sound is directed into the centre; everyone can now hear the complete sonority to which they are contributing, focusing the sound and also making them aware of balancing the parts: at particular points, one vocal line may be more important than the others, key notes in the chord colour the balance and influence the harmonic motion, and a moving line leads from one chord to the next. All these factors are significant, helping the singers understand the importance or the relevance of their contribution, and hence give meaning to their line and the way they sing it.

In our rehearsals, it’s become known as ‘Circle Time;’ a chance for everyone to get out of the rows in which they sit, to stand together and to hear a different sound. Move your singers around, and see how it affects the way they sing and the sense of ensemble the ensues: it’s sure to be different, and a positive experience.