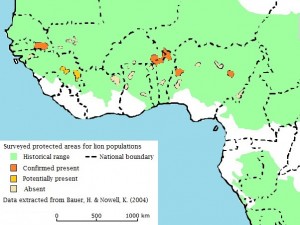

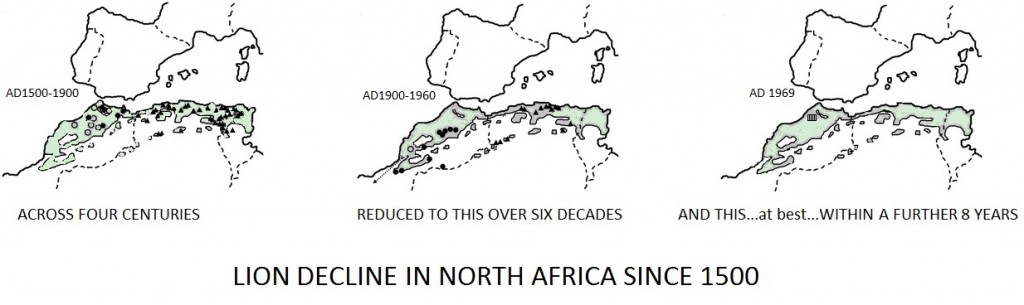

The barbary lion is extinct in the wild, most probably since the early 1960s.

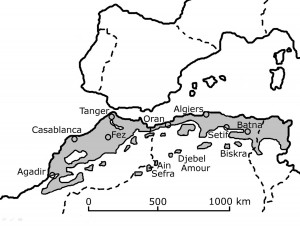

Up until that fairly recent time the Sultans of Morocco, followed by the Kings of Morocco after constitutional changes in the 1950s, kept lions in private menageries. These animals had been bred from cubs which were presented as tributes by Berber Tribes of the Atlas Mountains.

In the late 1960s the remaining lions were still in the King of Morocco’s lion garden at the palace of Fez, then later Rabat. After an outbreak of respiratrory disease in the collection in the late 1960s, the lions were then moved to a new purpose built zoo in Rabat in 1973 (Yamaguchi and Haddane, 2002).

The importance of this is that since that first transfer of animals, it has been possible to trace all lions of pure ancestry alive today back to their ancestors – these animals originally in the Moroocan Royal palace collection. This means that zoos holding these descendents have a unique opportunity to keep the bloodline pure, and alive. Efforts by a number of zoos in recent years (Port Lympne, Olomouc, Belfast, Hannover, Madrid) to make breeding transfers and to increase the number of cubs has enabled the population to recover. As recently as 2008 it looked like breeding of these animals was likely to cease and at least one unique bloodline from the original 27 animals moved from the Royal Palace to Rabat zoo was lost at this time when an old non-breeding female in Germany died.

A rejuvinated zoo population with active, well managed transfers of animals between collectiosn will geive enough time for deeper scinetific and genetic analysis to determine the uniqueness and deeper ancestry of these Moroccan animals and their significance to lion conservation.

Black S, Yamaguchi N, Harland A, Groombridge J (2010). Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions. Eur J Wildl Res 56: 21–31. doi: 10.1007/s10344-009-0280-5

Yamaguchi N, Haddane B. (2002). The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas Lion Project. International Zoo News 49: 465-481.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8109000/8109945.stm