In 2013 a book was published by Valmik Thapar which presented the idea that both the cheetah and the lion were most probably non-native species in India, introduced as captive animals from Africa or Central Asia, trained or used for Royal entertainment in the many substantial parks across the subcontinent and, with the demise of the various imperial and local royal dynasties between the 1200s and the mid 20th century, feral animals had become established as wild populations, hence the species now being seen as native (and rare – the lion, or extinct -the cheetah).

In 2013 a book was published by Valmik Thapar which presented the idea that both the cheetah and the lion were most probably non-native species in India, introduced as captive animals from Africa or Central Asia, trained or used for Royal entertainment in the many substantial parks across the subcontinent and, with the demise of the various imperial and local royal dynasties between the 1200s and the mid 20th century, feral animals had become established as wild populations, hence the species now being seen as native (and rare – the lion, or extinct -the cheetah).

This is an intriguing idea. The basis for these ideas runs from the lack of early accounts of either lion or cheetah in the region, but the subsequent rise of the follwing occurences in the time since Alexander the Great:

- An active series of royal hunting parks and hunitng as a royal passtime with the use of lions and cheetahs being particlualry culturally important

- Animals were exported to India from Central Europe and the middle east and also from Africa

- The genetics of Indian lions show inbreeding suggesting an originally tiny population (escapee captive animals)

- The genetics of captive Asiatic Lions (in the USA) shows traits of African subspecies.

- Indian lions are ‘tame’ relative to their African counterparts (including accounts form North Africa)

Thapar and his co-writers concede that they examine this as naturalists and hitorians, rather than from a deep scientific examination of evidence. But the proposal does raise testable questions:

What are the research implications?

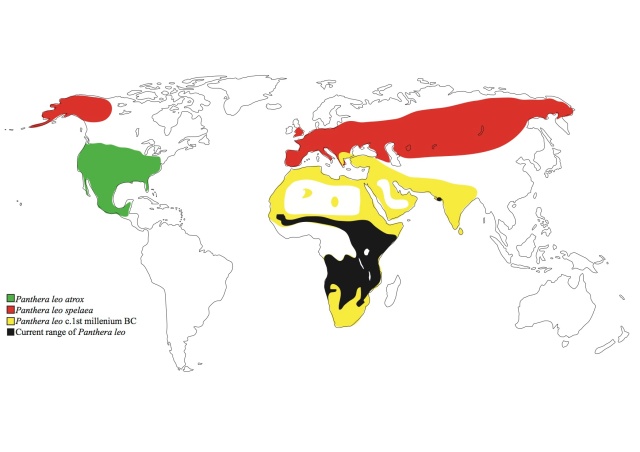

Do we understand the genetics of Indian lions relative to (and as different from) African lions? See recent work by Barnett et al. (2014).

Are all Asiatic lions Asiatic-African hybrids? This was the case in American Zoo animals in the 1980s – but those zoos may have mismanaged Asiatic-African pairings in captivity earlier in the 20th century.

What are the conservation implications?

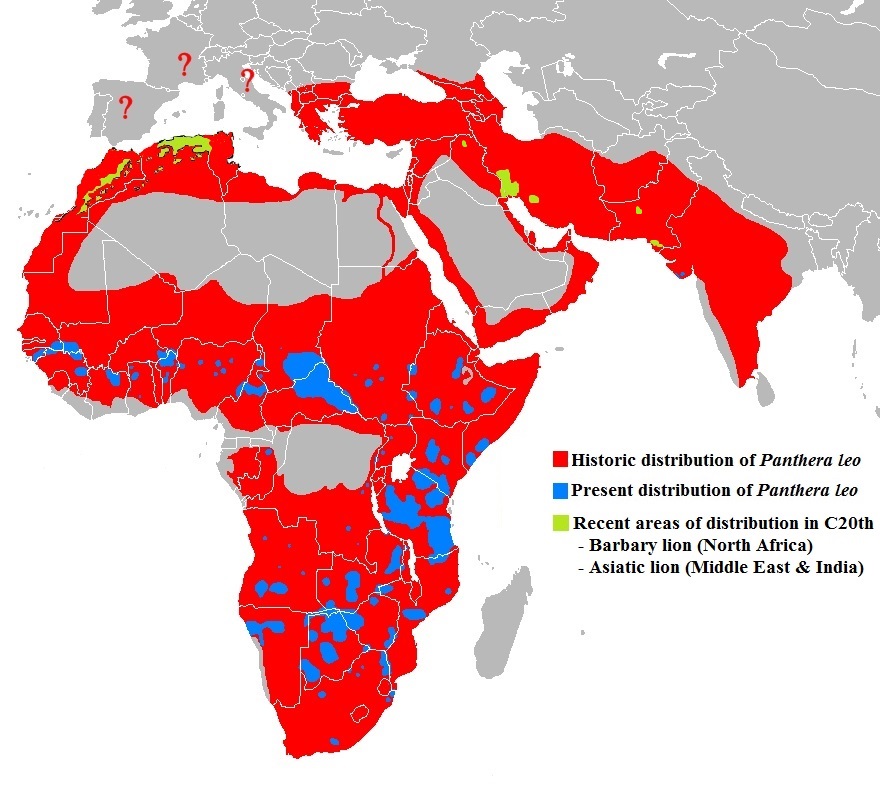

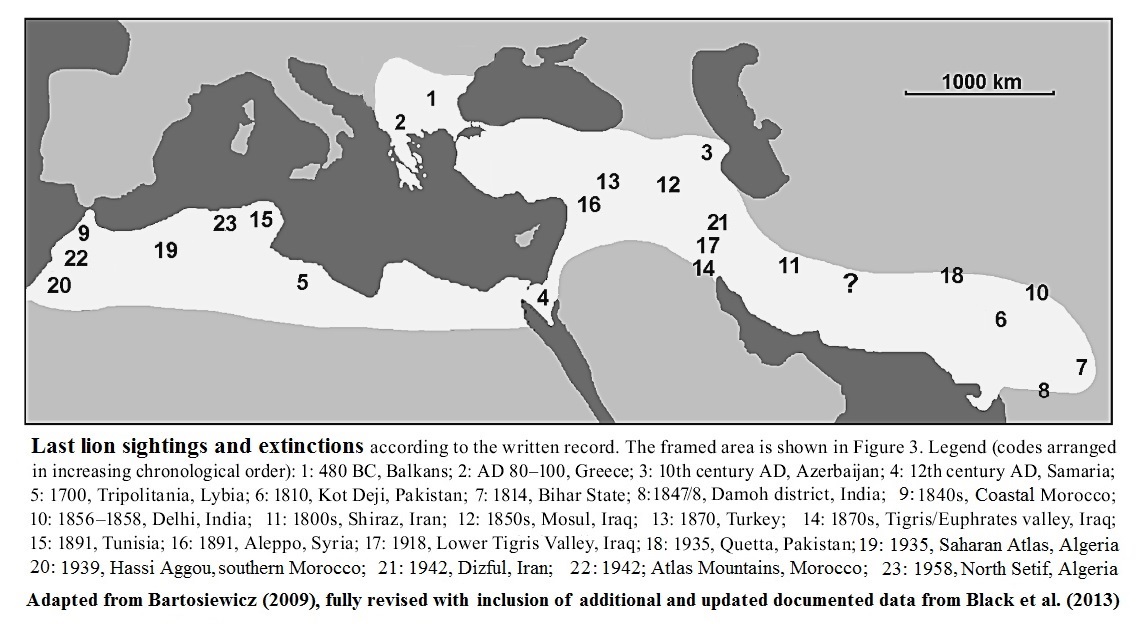

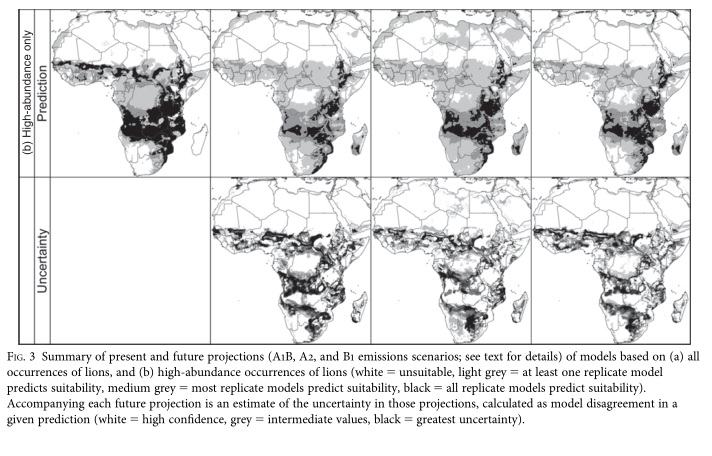

Should Asiatic lions still be conserved? – YES – even if they are non-native to India, they are the last remnants of the lions which once ranged from Egypt to India (i.e. to the banks of the Indus river).

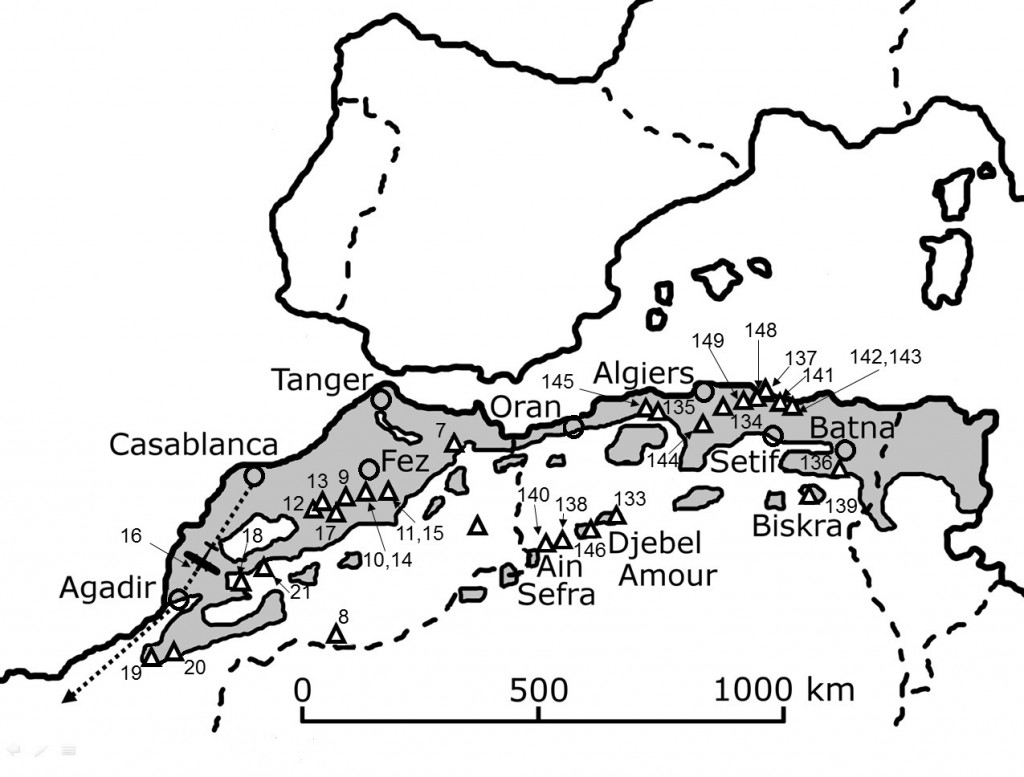

Might Indian lions be close relatives of Barbary Lions? – This is an intriguing possibility (see Barnett et al. 2014).

What about an Indian – Moroccan Royal lions Hybrid? – if Indian lions are ‘tame’ (which is NOT the case with many captive Moroccan Royal lions), then you could out-breed ‘tameness’ and retain an authentic the asiatic (northern) subspecies of lion. Similalry Asiatic lioins could eb used to retain or ‘clean up’ the Moroccan lions if they are wshown to be Barbary/subSaharan hybrids.

There is little reason to accept Thapar’s hypotheses. Improvements in genetic analysis will enable us to better understand lion phylogeny in due course. In the meantime, precaution suggests continued efforts in Indian lion conservation are strongly recommended.

Reading:

Anon (2014) New Genetic Study Reconstructs Distribution History of Lion. Sci-News.com http://www.sci-news.com/genetics/science-distribution-lion-01892.html

Barnett, R. et al. (2014) Revealing the maternal demographic history of Panthera leo using ancient DNA and a spatially explicit genealogical analysis. BMC Evolutionary Biology 14: 70; doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-70

Thapar V., Thapar R., and Ansari Y. (2013) Exotic Aliens: the lion and cheetah in India. Aleph, India.

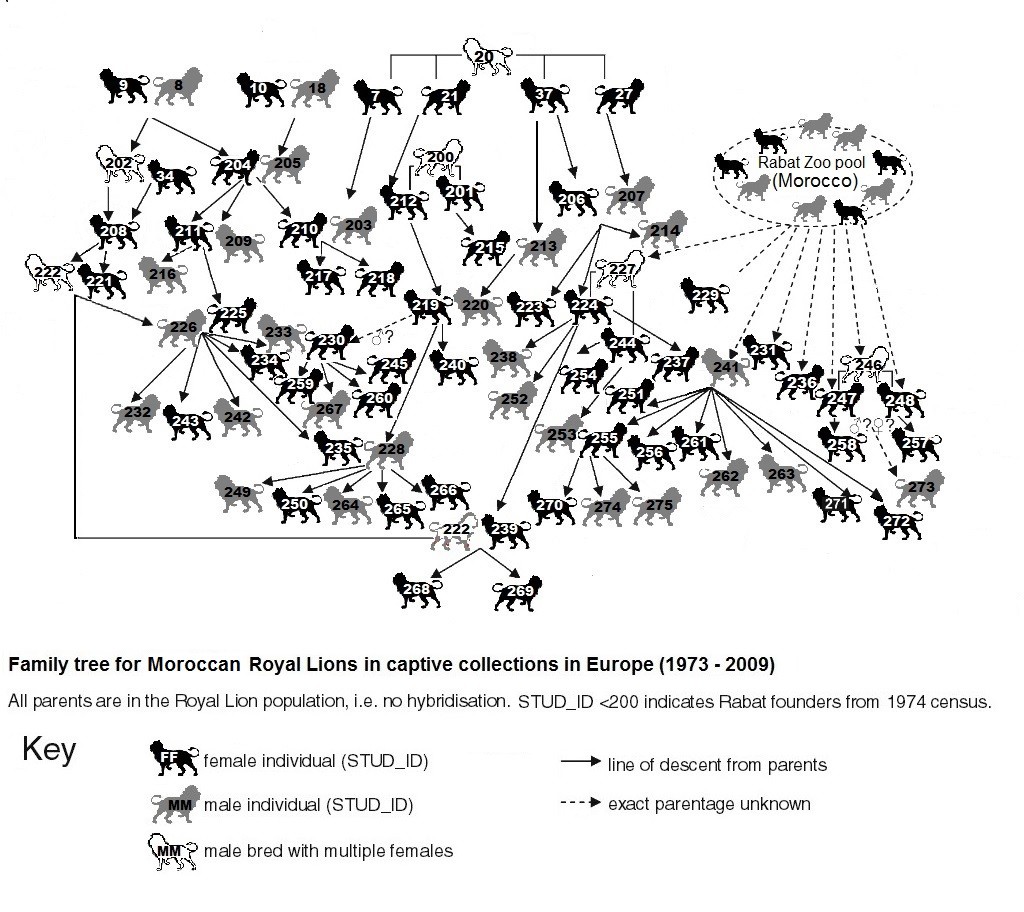

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.