Special contribution

Lara J. Bazzu

Worcester Prize Winner 2021, Durrell Institute of Conservation & Ecology

The distinctiveness of Barbary lions

Figure 2. A Moroccan lion at Olomouc Zoo, Czech Republic in 2000. This individual has many of the 12 morphological traits, assumed to discriminate a “pure” Barbary lion (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002).

North African lions were considered unique amongst lion populations because of their morphology (Figure 2) and behavioural ecology (Black 2016). They lived in a variety of habitats in the Maghreb (Black 2016), the area that extends from the Atlas Mountains to the Mediterranean (Lee et al. 2015) including lowland coastal plains, forests, mountains and semi-arid areas fringing the Sahara (Black 2016).

Notably, Barbary lions were adapted to a temperate climate with cold winters (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002). The Barbary lion lived a more solitary existence, possibly as the result of lower prey densities in temperate habitats (Mazak 1970), but was also seen in family units comprising male, female and cubs (Black et al. 2013) which contrasts with the familiar, larger ‘prides’ observed in sub-Saharan Africa lions (Mazak 1970).

Historical range of the Barbary lion

Prior to the 18th century Barbary lions still roamed widely across the Maghreb region (Black et al. 2013) which along with coastal northern Libya, comprised the lion’s original range (Black 2016). By the 19th century, bounties issued by Turkish authorities contributed to the decrease of countless lions in western North Africa and later during French control of Algeria, rewards for lions were continued and many lions were killed between 1873 and 1883 (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002).

In Morocco lions initially fared better since the country was ruled by the sultan (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002) but continued widespread persecution in the 19th century left the animals isolated in separate remote areas in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (Black et al. 2013). The last lion in Tunisia was killed in 1891 (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002). Strikingly, the last visual proof of a Barbary lion in the wild is a 1925 aerial photograph (Figure 3) in Morocco from a Casablanca-Dakar flight (Black et al. 2013).

A lioness killed much later, in 1942 in the High Atlas mountains of Morocco, had been considered the last encountered in the wild (Lee et al. 2015). However, tiny populations seem to have persisted in Algeria and Morocco for years (Black et al. 2013) with sporadic sightings extending up to the 1960s (Figure 4). The Barbary lion’s final demise is thought to be the result of military conflict, when the forests north of Setif were destroyed in the French-Algerian War in 1958 (Black et al. 2013).

Figure 4. Last sightings of lions in North Africa (1900-1960). Grey shading depicts Mediterranean ecosystems. Triangles indicate sightings in Algeria and Tunisia and circles for sightings in Morocco. The dotted line is the Casablanca-Agadir-Dakar air route. Dashed lines are national borders and asterisks are towns (Black et al. 2013)

Relevance of sightings for lion conservation today

A later extinction date for Barbary lions provides lessons for conserving current lion populations in West and Central Africa (Black et al. 2013). The Barbary lion story illustrates how micro-populations can remain undetected for generations (Black et al. 2013) as recently observed in Gabon. Lions were declared extinct in Gabon in 2006 yet one was seen on a camera trap in 2017 in the Plateaux Batéké National Park and subsequent DNA sampling established that it belonged to the ancestral Batéké population (Barnett et al. 2018). A lack of sightings of lions may mean conservation effort ceases (Lee et al. 2015), yet research on past sightings suggests assumption of persistence is more sensible.

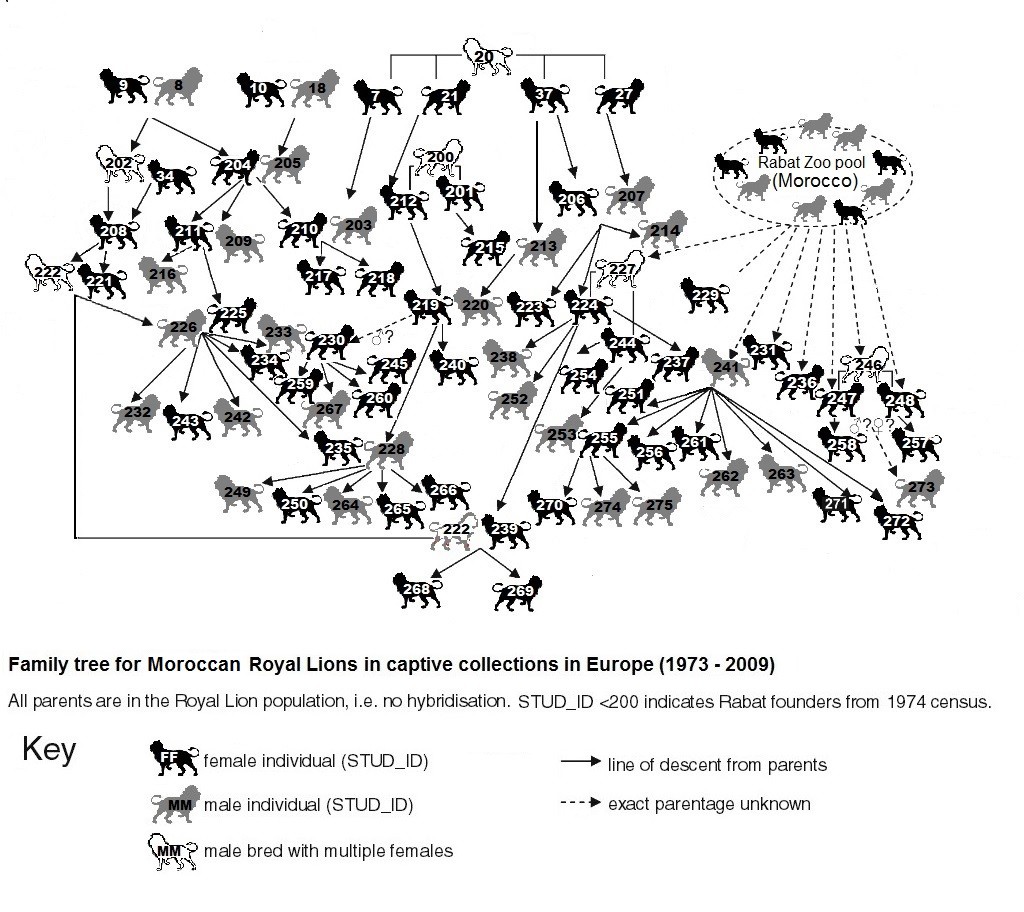

Connection between Moroccan lions and Barbary lions

Intriguingly, descendants of Barbary lions may be in captivity today, thanks to the sultans and kings of Morocco, whose lion collection was derived from animals obtained by Berber tribes in the Atlas mountains (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002). Genetic links to Barbary lions are yet to be verified and Moroccan lions are not yet officially recognised as Barbary (Black et al. 2010), since historical mixing of Moroccan lions with sub-Saharan lions cannot be ruled out (Burger and Hemmer 2005). However, the precautionary principle favours conservation of the Moroccan lineage at least until science proves otherwise (Black et al. 2013). Captive Moroccan lions are found in zoos in Europe, Morocco and Israel (Black et al. 2010), with new cubs born in Neuwied, Pilsen, Hannover, Erfurt, Heidelberg, Plättli, Olomouc, Port Lympne and Rabat. Clearly, for breeding to be purposeful, the goal should be to return animals to the wild, to support survival of the northern subspecies P. l. leo (Black 2016).

Potential for reintroduction in the wild

The habitats of the Maghreb region have seen dramatic degradation in the 20th century as a result of human expansion, drought and primarily, overgrazing (Slimani and Aidoud 2004). Lions have been absent from the area for more than 60 years (Black 2016) which means their ecological role in the region is also lost, potentially influencing land impoverishment. In order to restore the North African ecosystem, the reintroduction of two lion types has been proposed: the Moroccan lion if/when its connection to the Barbary lion is substantiated, or from the same subspecies, the Asiatic lion, which today inhabits India (Black 2016) and is also in a perilous state. Any reintroduction would require careful planning, habitat development, prey population management, community involvement and monitoring to enable a shift from small scale pilot studies to a wider scale landscape recovery.

There is a chance that people may once again be able to see lions against the backdrop of the snow-covered Atlas mountains and hear the echo of roars as described by Ormsby in 1864 (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002). It would be a fitting soundtrack for restored forests and valleys in North Africa.

References:

Bazzu L.J. and B;ack S.A. Les lions d’Afrique du Nord : apprendre du passé pour façonner le futur. (translated C. Guy) Le Tarsier (Association Francophone des Soigneurs Animaliers) 26, 5-9.

Black, S. (2016). The Challenges and Relevance of Exploring the Genetics of North Africa’s “Barbary Lion” and the Conservation of Putative Descendants in Captivity. International Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2016, 1-9.

Black, S., Fellous, A., Yamaguchi, N. and Roberts, D., 2013. Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e60174.

Black, S., Yamaguchi, N., Harland, A. and Groombridge, J. (2010). Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 56(1), 21-31.

Burger, J. and Hemmer, H. (2005). Urgent call for further breeding of the relic zoo population of the critically endangered Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo Linnaeus 1758). European Journal of Wildlife Research, 52(1), 54-58.

Lee, T., et al. (2015). Assessing uncertainty in sighting records: an example of the Barbary lion. PeerJ, 3, e1224.

Mazak V. (1970). The Barbary lion, Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758); some systematic notes, and an interim list of the specimens preserved in European museums. Z Saugetierkd 35,34-45.

Slimani H. and Aidoud A. (2004) Desertification in the Maghreb: A Case Study of an Algerian High-Plain Steppe. In: Marquina A. (ed) Environmental Challenges in the Mediterranean 2000–2050. Vol. 37. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 93-108.

Yamaguchi N., Haddane B. (2002). The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas lion project. Int. Zoo News, 49, 465–481.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.

By the end of the 1990s efforts by several zoos to engage in a pan-European breeding programme for lions derived from the King of Morocco’s collection was beginning to fade. Only Port Lympne continued with an active breeding group, and a male from Rabat zoo (number 241 on the diagram opposite) was brought in to reinvigorate a pride which was developed from animals imported from Washington zoo in the 1980s. Up until that point they had reached a point of inbreeding within a family group.