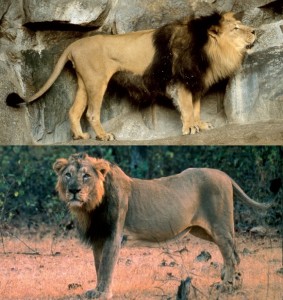

Moroccan lion, Port Lympne Reserve, UK. Can this animal offer something different for global lion conservation? (Photo: S Black)

The IUCN is looking to re-designate the taxonomy of lions, splitting them into two sub-species. Most lions in zoos are descended from East, North Eastern and Southern African lions, Panthera leo melanochaita, of which there are about 30,000 in the wild. Lions from India and West and Central Africa are a separate, highly endangered group of just 1500 individuals in the wild, Panthera leo leo (Bertola et al, 2016; Black 2016). Of the latter group perhaps 100 are kept in zoos, all originating from India.

Lions descended from animals held in the collection of the King of Morocco (and Sultans before) have been kept as a distinct group for decades. It is possible that today’s Moroccan lions are part of P. l. leo, the highly endangered group (Black 2016).

Moroccan lions number just under 100 captive animals – potential direct relatives of animals spread across the northern distribution – a vital breeding pool for future lion survival. Moroccan lions are still successful breeders in captivity.

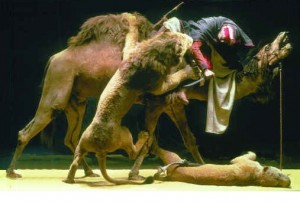

Globally, lions have declined by about 90% in recent decades. Most of the 30,000 left are in Eastern and Southern Africa (Panthera leo melanochiata) . Of the few remaining in the ‘northern’ sub-species (Panthera leo leo ) populations can be counted as follows:

* India – 400 in the wild – 100 in captivity

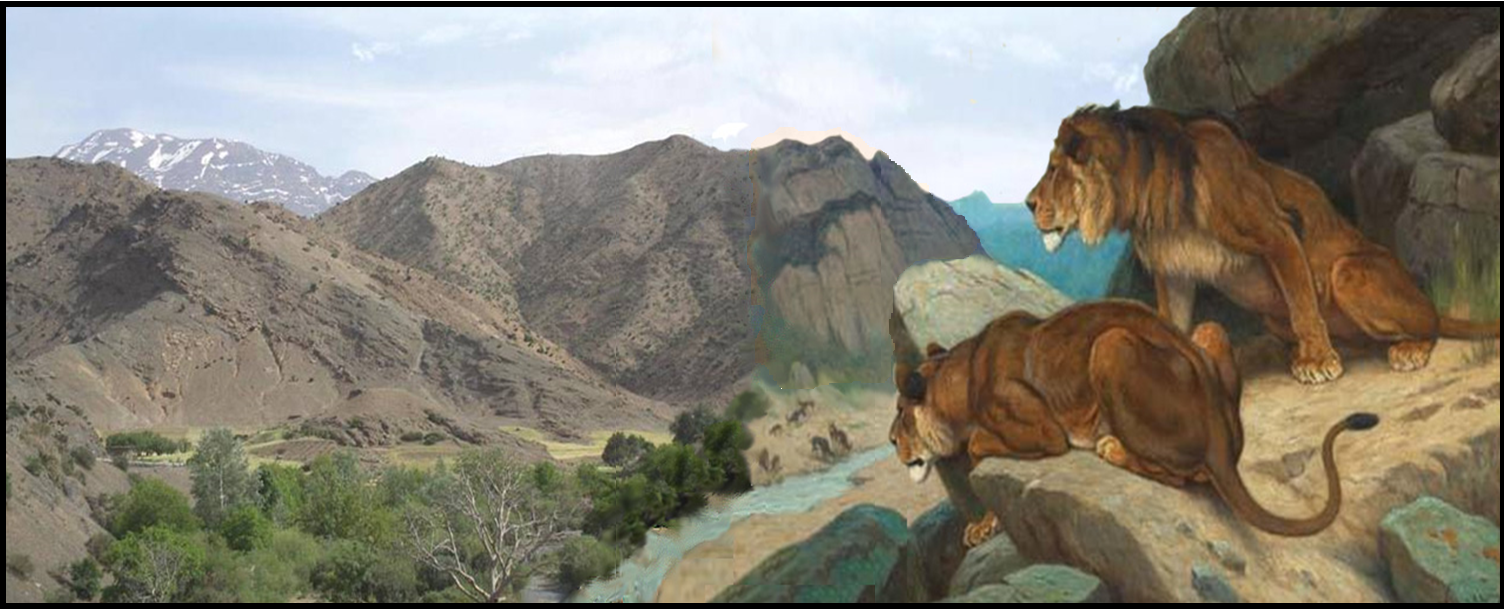

* Middle East – extinct since the 1940s

* North Africa – extinct since the 1950s

* West Africa – about 250 in the wild

* Central Africa – about 800-1200 in the wild

There are few if any lions from West and Central Africa in zoos today and only 100 captive animals verified in the Indian lion studbook. If the 80 animals in the Moroccan Royal group (in Rabat zoo and in European zoos) are proven to be closely related, they will add significantly to the gene pool. The Moroccan animals in zoos may be the last chance to save the subspecies from disappearance in Africa.

Additionally, Morocco itself could become a wild safe harbour for reintroduction of animals, despite no lions being in the wild since the 1950s. This would also give a long term base from which to support lion recovery in West Africa, for example.

Whilst the IUCN revision of taxonomy puts a number of subspecies debates to bed, it also provides real clarity of the the threat to Panthera leo leo and its vulnerability in isolated pockets across west and central Africa and North-west India. It is staggering to consider that just a few hundreds of animals are spread across these vast areas of previous habitat.

The conservation landscape for lions has changed dramatically in the wild. Now the Moroccan Royal lion population has quite possibly become more important than ever.

Reading:

Bertola, L. D.,et al. (2016) Phylogeographic Patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of Genetic Clades in the Lion (Panthera leo). Scientific Reports 6:30807. DOI: 10.1038/srep30807

Black S.A. (2016) The Challenges of Exploring the Genetic Distinctiveness of the Barbary Lion and the Identification of Putative Descendants in Captivity, International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. vol. 2016, Article ID 6901892, 9 pages, 2016. doi:10.1155/2016/6901892