The dates of final extinction of the Barbary Lion have been a favourite topics of speculation for many commentators big cat decline in recent decades. Typical dates encountered in books and on the web include

An authentic sighting?

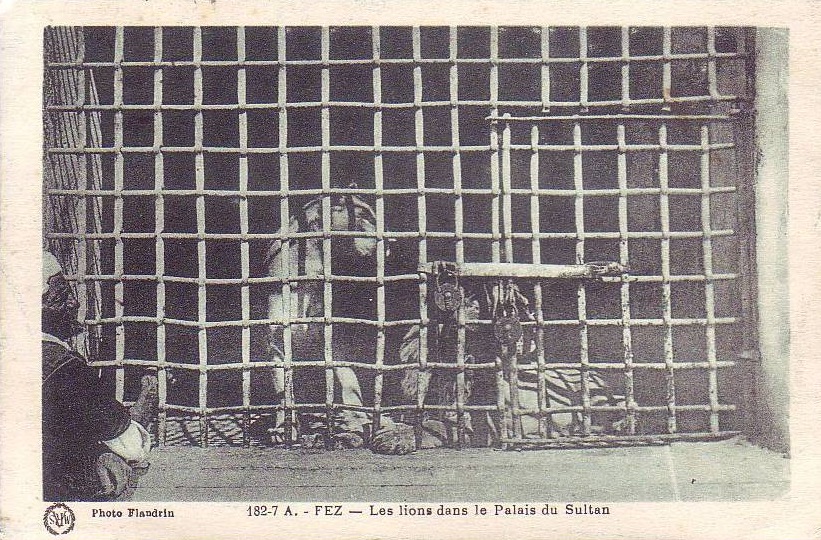

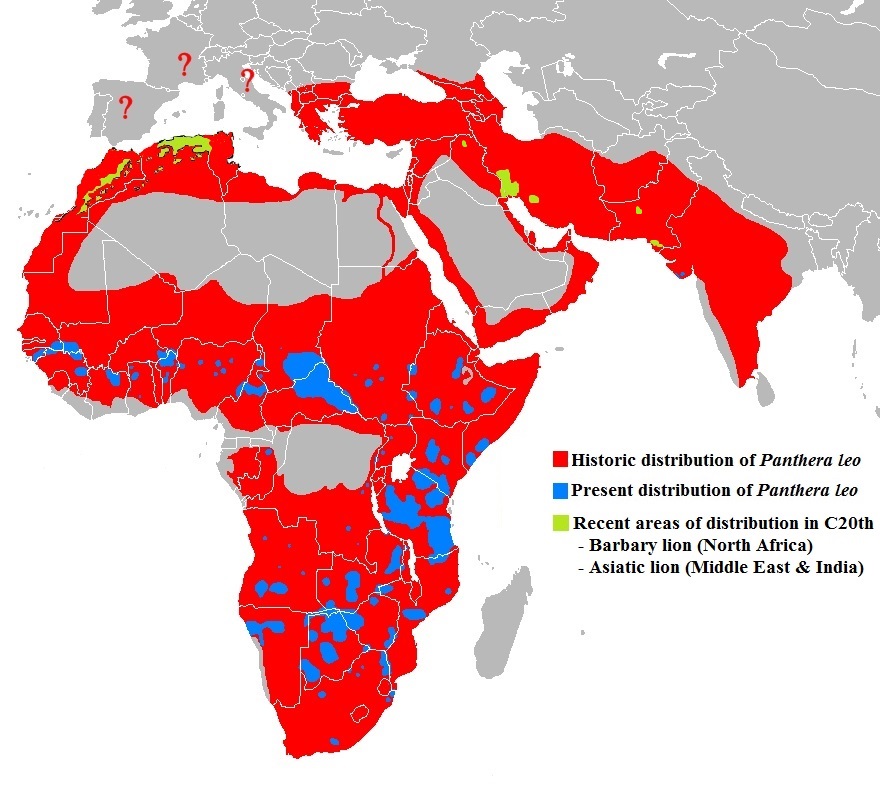

The Barbary lion was known to range Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. Any other populations in the Libyan desert and into Egypt were very sparse and probably disappeared in ancient times, probably before the rise of human civilisation in the region (Yamaguchi and Haddane, 2002). Although hundreds of lions were exported for the Roman Games and Berber tribes took cubs as gifts in the 1600s through to the 1800s, the major culls of the population occurred in the 1800s as part of a colonial pest control programme (particularly in Algeria). Later in the century encounters were generally made by hunters or farmers.

Typically, the story goes that the last lion was shot in Morocco in 1927 (or 1921), but this date is based on rather superficial knowledge of available accounts (someone said ‘the last lion was shot on that date’, so that must mean the last lion was shot on that date, and so on). Some accounts are based on a proposal (perhaps by a local personality) as an assertion of knowledge, rather than on a detailed cataloguing of specific sightings.

A dig into the literature reveals suggestion of later dates by well-established scholars including Cabrera (1932), Guggisberg (1963) Hemmer (1978) each of whom made well-researched projections on the dates for likely extinction of lions based on collations of accounts in previous decades. All three of these commentators suggest survival of lions in North Africa into the 1930s.

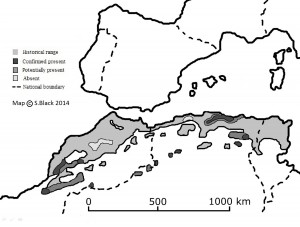

However any of ‘best judgement’ is inevitably compromised by (i) the ranging of populations across national boundaries, (ii) the remoteness of available habitat areas (and therefore likelihood that narrative accounts will be recorded for such localities), (iii) confounding factors such as reported sightings of domesticated animals or confusion with other wild species, and (iv) the reputability of the eyewitness account. Even a cursory glance at the two maps produced by Black et al (2013) illustrates that sightings of lions ‘shifted’ from the northern coastal regions (up to 1900) broadly southwards to the remote regions bounding the Sahara. Of course, this shift is a combination of removal of lions from Northern areas and (prior to 1900) a lack of visitors to the remoter southern fringes fo the Maghreb (due to war, lack of road access and relatively inhospitable terrain).

A number of researchers working in North Africa over the past 20 years, particularly Dr Amina Fellous, Dr Fabrice Cuzin and Prof Mohan Haddadou have encountered testimonies by local people during interviews which describe fairly recent encounters with lions in remote areas. Recent research using both the historical record and new interview evidence combined with probability modelling has identified that lions disappeared from Morocco and Algeria around the late 1950s /early 1960s. Over 50 years earlier the population had shrunk from its former range spanning both Tunisia and Algeria – and no lions have roamed in Tunisia since the 1890s.

Further Reading:

Black SA, Fellous A, Yamaguchi N, Roberts DL (2013) Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation. PLoS ONE 8(4): e60174. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174

Yamaguchi N, Haddane B. 2002. The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas Lion Project. International Zoo News 49: 465-481.

The last record of lions in Iraq was possibly the two shot by a Turkish governor in 1914 near Mosul and later in 1918 in the lower Tigris . The last Iranian lions had largely dissappeared in the 1940s with sporadic sightings by railway engineers in the years during the second world war. A lion was also thought to have been seen near Quetta in Pakistan in 1935.

The last record of lions in Iraq was possibly the two shot by a Turkish governor in 1914 near Mosul and later in 1918 in the lower Tigris . The last Iranian lions had largely dissappeared in the 1940s with sporadic sightings by railway engineers in the years during the second world war. A lion was also thought to have been seen near Quetta in Pakistan in 1935.