The growth in knowledge of genetic technologies has raised the topic of “De-extinction”, the recovery of extinct species. But is it worth spending money and resources to produce a conservation ‘gimmick’, like a resurrected mammoth? This is a question of ethics; the value of a curiosity. But there are practical implications as well; if we are to reintroduce species into the wild, are we really good enough at reintroductions to make this a success (Donlan 2014)?

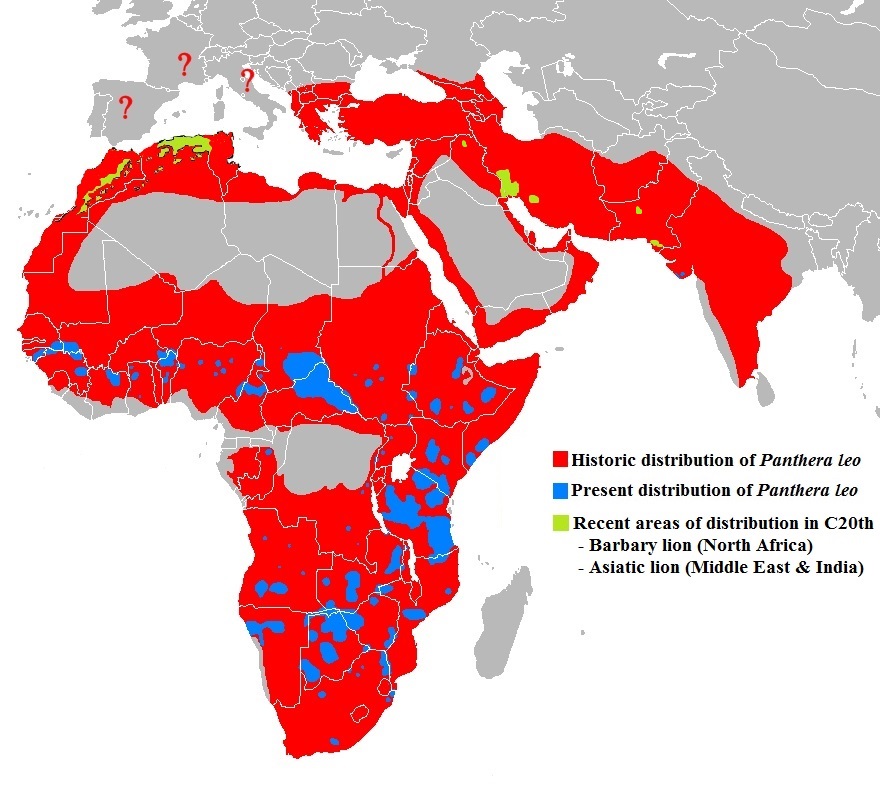

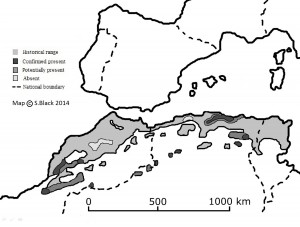

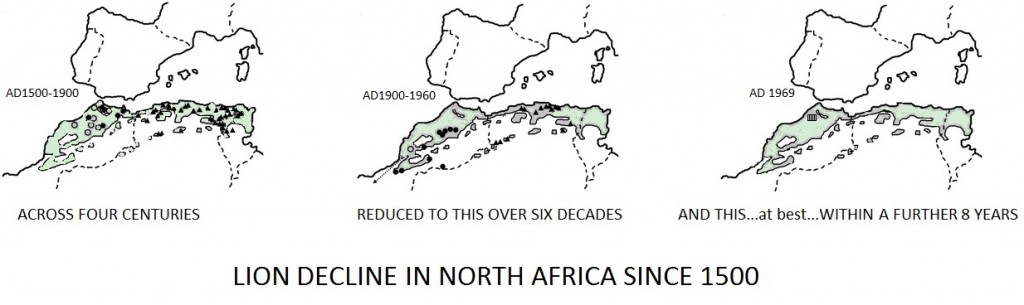

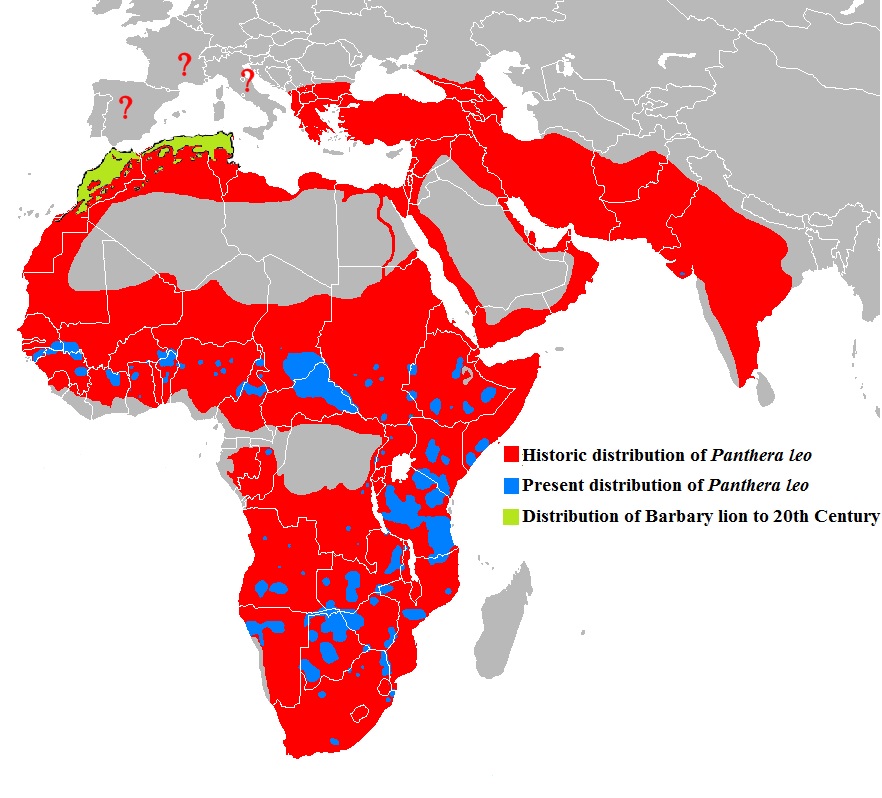

De-extinction discussions often relate to famous species such as the Woolly Mammoth, Passenger Pigeon, Dodo and Thylacine and are often criticised for the “Jurassic Park” element of the argument. However one step back from those more spectacular proposals are recently lost sub-species including the Barbary Lion (Jones, 2014) as potential ambassadors or mascots for conservation and biodiversity recovery in their lands of origin. This prospect has been the on-off discussion concerning the fate of the lions of the Kings Collection in Morocco for decades (Nowell and Jackson 1996).

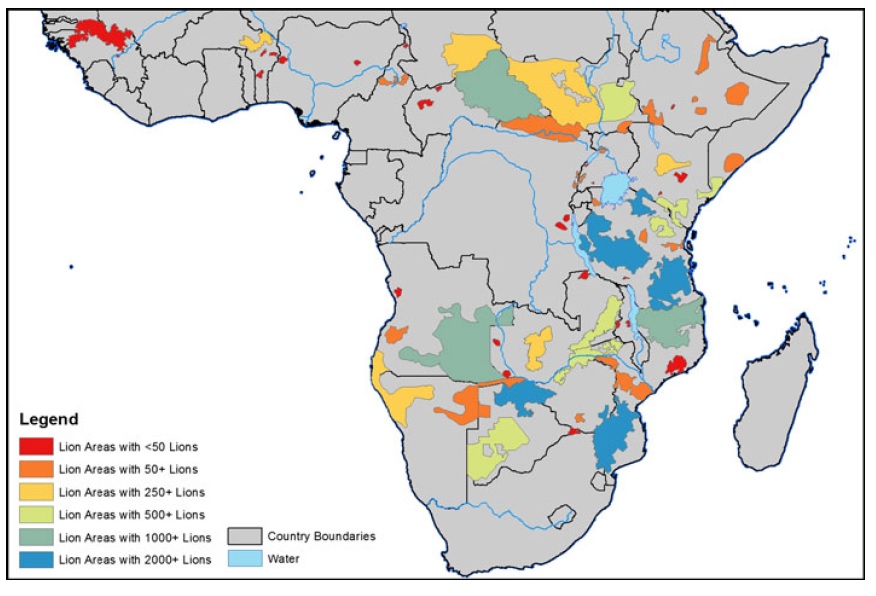

However, the argument for this type of work needs to go deeper. Recovery of such a formidable species into the wild requires a transformation in the landscape and in the thinking of local people, including the conservationists themselves to develop a sensible and worthwhile model of reintroduction. Reintroduction must match biology, socio-economics, local culture and politics – and most of these factors do not involve scientific expertise, but skills and knowledge in quite different aspects of work.

Reading:

Donlan, J. (2014) De-extinction in a crisis discipline. Frontiers of Biogeography, 6(1) http://escholarship.org/uc/item/2x70q4nk

Jones, K.E. (2014) From dinosaurs to dodos: who could and should we de-extinct? Frontiers of Biogeography, 6(1) http://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gv7n6d3

Nowell K., and Jackson P. (1996) Wild cats, status survey and conservation action plan. Gland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.