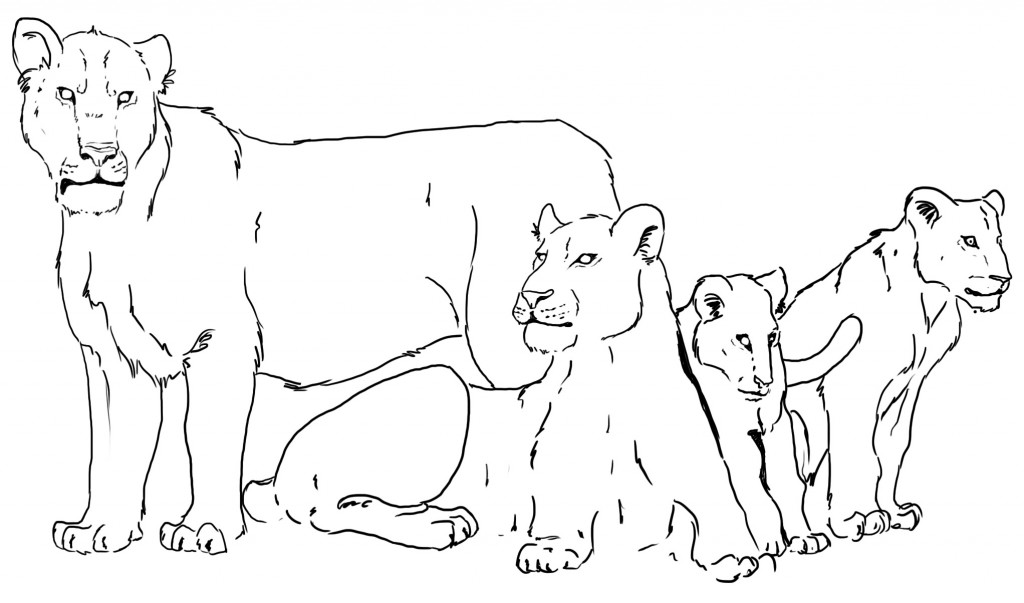

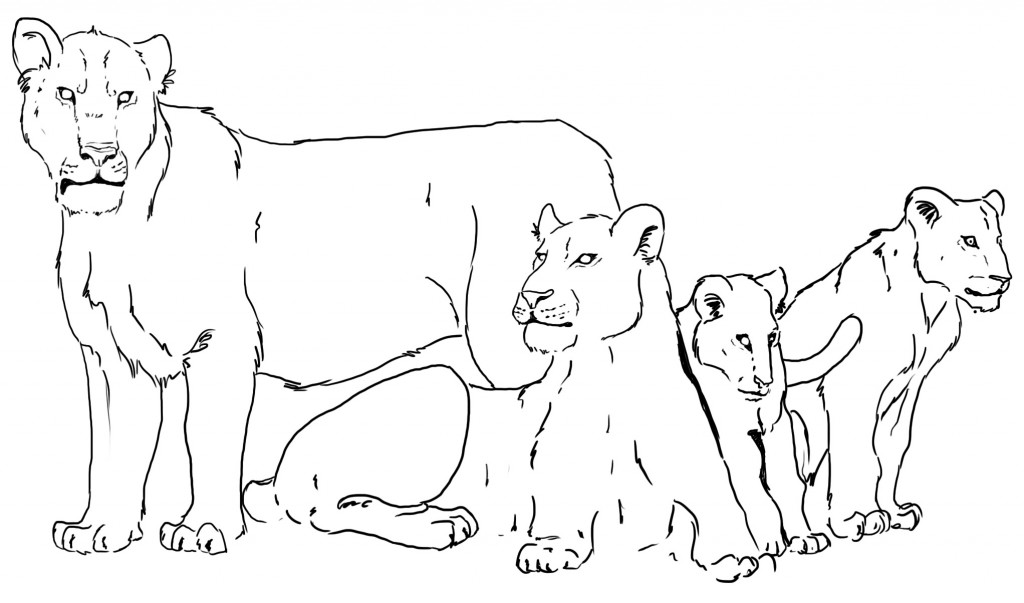

Sketch of a pride of Cave lions. Note the lack of manes on the big standing male. Art by Tabitha Paterson (@TabithaPaterson)

We think of lions, today, as African animals. This is mostly true. However, there is still a tiny refugium of non-African lions, isolated in the Kathiawar peninsula of India, and centred on the Gir forest reserve. Here, 400 or so Asian lions eke out an existence, beset on all sides by people and farmland, the last remnants of an empire that once spread from Tunisia via Turkey to the Tigris and beyond. But, even this is only a fraction of the range that lions once held.

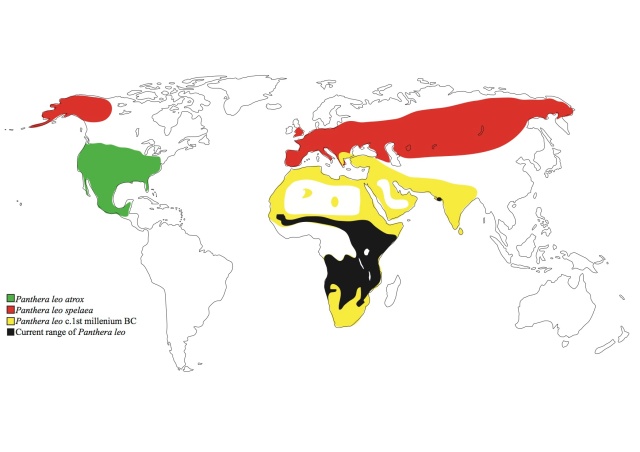

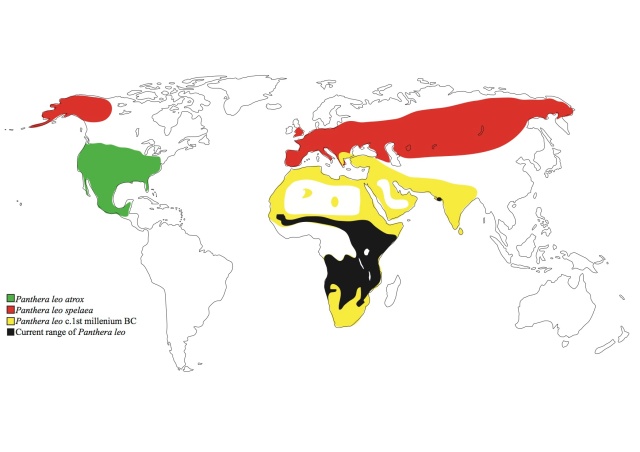

During the Pleistocene, highly differentiated lion subspecies (or perhaps separate species, opinion is divided) roamed from Spain to Siberia, through the steppes of Beringia, and into the Americas as far south as Mexico. Their fossils are surprisingly common in Britain too. In fact, excavation of the site of Trafalgar square uncovered a number of lion fossils where now their equally impressive bronze cousins lie today. The cave lion (Panthera spelaea) occupied all of Eurasia and Beringia. The closely related American lion (Panthera atrox) was found over the contiguous lower 48 states.

Range of lions since the Pleistocene. Image by Ross Barnett

The cave lion is, and was, a pretty special felid. Considerably larger than modern lions, it was the apex predator of the Pleistocene food web (with perhaps some competition from Homotherium). As it lived in Europe at the same time as anatomically modern humans, it has been depicted in numerous pieces of parietal and portable art. The cave walls of Chauvet and Lascaux contain brilliantly realistic images of this extinct animal, showing that it lived in prides, and that males were maneless. We know this because in a few images, the adult male scrotum is obvious, and the mane is absent.

Pride of cave lions from Chauvet cave. Public domain image.

It also seems that early Europeans had some kind of cultural affinity for the cave lion. One of the most amazing pieces of art to come from this period, exquisitely crafted from mammoth ivory, shows a half-lion, half-human chimera. This löwenmensch, as it is known in german, testifies to some kind of ritual or mythic importance for the cave lion in the culture of the time. Like the venus figurines, löwenmensch, have been found at multiple sites, showing that the idea was not just an isolated one but shared amongst communities.

Löwenmensch from Hohlenstein-Stadel. Image by Dagmar Hollmann via Wikimedia Commons. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Further reading:

Nice piece by the Telegraph, featuring our very own Ross Barnett: ‘Super-sized lions’ roamed UK in Ice Age.

Barnett, R., et al. (2014), ‘Revealing the maternal deomgraphic history of Panthera leo using ancient DNA and a spatially explicit genealogical analysis’, BMC Evolutionary Biology, 14, 70. [Full Article]

Barnett, R., et al. (2009), ‘Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity’, Molecular Ecology, 18 (8), 1668-77. [Abstract]

Conard, N. J. (2003), ‘Palaeolithic ivory sculptures from southwestern Germany and the origins of figurative art’, Nature, 426 (6968), 830-32. [Abstract]

Franks, J. W. (1960), ‘Interglacial deposits at Trafalgar Square’, The New Phytologist, 59, 145-150Montellano-Ballesteros, M. and Carbot-Chanona, G. (2009), ‘Panthera leo atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico’, The Southwestern Naturalist, 54 (2), 217-22. [Abstract]

Montellano-Ballesteros, M., and G. Carbot-Chanona (2009). ‘Panthera Leo Atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico.’ The Southwestern Naturalist 54, no. 2 , 217-22. [Abstract]

Packer, C. and Clotte, J. (2000), ‘When Lions Ruled France’, Natural History, 109, 52-57. [Full Article]

Posted on BarbaryLion with thanks to Ross Barnett and colleagues at

TwilightBeasts:

Jan Freedman (

@janfreedman),

Tabitha Paterson (

@TabithaPaterson), and

Rena Maguire (

@justrena).

he history of lion presence in countries across North Africa, and investigation into the final decline of the species in the region and the lessons which need to be learned for current lion declines in West and Central Africa are discussed.

he history of lion presence in countries across North Africa, and investigation into the final decline of the species in the region and the lessons which need to be learned for current lion declines in West and Central Africa are discussed.