The best thing about working on the Lady’s Magazine project is working as part of a team. I’ve worked with colleagues before on conferences and workshop series, and have learned so much from editing with friends. But this is really the first time that I can honestly say that I have researched collaboratively. It’s not the most common model for humanities research, and not all projects would require or possibly even much benefit from this approach.

Honestly, though, nearly a year into our project, I couldn’t imagine having continued my work on it without Jenny and Koenraad, aka my academic consciences, who keep me enthused and keep me honest by questioning my conclusions and nudging me to think differently week by week. We work together in a manner not dissimilar from the way that contributors to the magazine worked with each other: collaboratively, conversationally. Anything we say can be picked up and run with (or unceremoniously dropped) by anyone else. Our contributions to that conversation get better the more they are encouraged or challenged by others.

But like the magazine’s contributors, we don’t always reach a consensus. It’s not often that these disagreements are profound, but they are always important because they tend to strike at the very heart of what we think is at stake in our research and why it might (or might not) matter. The most recent of these few flash-points has been around what I have come now to refer to as ‘the P-word’: plagiarism. It’s not a term I find easy to associate with eighteenth-century periodicals, even though the Lady’s Magazine itself was not averse to using it. So what is my problem with the P-word, and why I am resisting its use in our index?

The fact is that a significant number of contributions to the Lady’s Magazine were originally published elsewhere. The periodical did not conceal this fact from its readers. Often such extracts were published with their original author’s name and the full title of the work from which they were extracted or republished in full underneath the article headers. Indeed, the magazine was quite clear throughout its history that it would serve as a miscellany of works from ‘the whole circle of Polite Literature’ as appeared to the editor or editors to ‘merit their readers’ attention’, as well as providing a forum for the numerous original and amusing communications which we continually receive from our ingenious and liberal correspondents’ (‘Address to the Public’, LM XXIII [Jan 1972]: iv).

Rather more has been made in the slender body of scholarship on the Lady’s Magazine, including my own, about these ‘original and amusing communications’ than its miscellany content. There are, I think, good reasons for this. The tantalising prospect and, as this blog has already demonstrated several times over, the satisfying reality of locating previously widely-read texts by largely unknown authors such as C. D. Haynes (later Golland), John and Elizabeth Legg, Catharine Bremen Yeames and Elizabeth Yeames and John Webb recalibrates our sense of the authorial landscape in our period in ways that I still believe are potentially far-reaching in their implications.

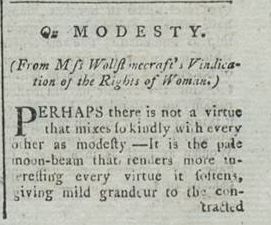

That said, we overlook the miscellany content at our peril. Apart from simply filling so many of the magazine’s pages, this material gives us clues as to the shifting priorities of the magazine as it shaped or responded to oscillations in literary taste and notions of female education, for instance. It also provides clues as to how published works were disseminated and received by their readers. Knowing that some selections from Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) made it into the magazine in June 1792 might seem only to confirm things we already knew: for instance, that Wollstonecraft’s work was part of the public consciousness immediately after its publication; and that the Lady’s Magazine‘s publisher, George Robinson, was sympathetic to the Jacobin cause.

LM VXIII (June 1792): 285. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Librarr. Not to be reproduced without permission.s

But only reading these extracts will tell you which aspects of Wollstonecraft’s work – her condemnation of false modesty and excessively sensibility – were deemed most worthy of the attention of the magazine’s readers. Moreover, only engaging with this content will give an indication of how the material might have been read. Given that many readers only engagement with Wollstonecraft’s work likely derived from the extracts printed in the popular press, examining such extracts as extracts is an important part of building up a sense of her work’s early reception history. If a reader’s engagement with Wollstonecraft’s work was confined only to these extracts, how does A Vindication of the Rights of Woman read? What does it seem most to be about?

The questions that arise from the publication of such extracts would merit a whole series of blog posts or book chapters of their own. Instead I want to focus briefly here on another kind of extract the magazine publishes: extracts that aren’t acknowledged as such.

As Koenraad has recently explained, he is currently doing battle with the herculean task of seeking out whether seemingly original (because not acknowledged as unoriginal) articles in the Lady’s Magazine were, in fact, written expressly for it. So far, he has identified a number of sources (some unexpected!) for material in the magazine. Some of this material has no signature underneath it; some of it appears with a pseudonym and therefore might seem to be the work of one of the reader-contributors about which we (OK, I) get so excited. Neither of these things is the case.

But are these plagiarisims? The short answer is: I don’t think so.

Plagiarism is a notoriously difficult term to pin down or prove in the eighteenth century and Romantic period. As Tilar Mazzeo’s wonderful book Plagiarism and Property in the Romantic (2007) elucidates, plagiarism was not a criminally chargeable offence with ‘direct legal consequences’ in the period (10), and was often considered more of an aesthetic rather than moral or legal question. Throughout her book, Mazzeo distinguishes between ‘culpable’ and ‘aesthetic’ plagiarism. Culpable plagiarism is unacknowledged yet conscious – a definition that chimes with our own modern sense of what constitutes literary fraud – but arguably more important is that culpably plagiarised work is unimproved. Work that has been improved, taken and reworked or repurposed by another hand, is arguably not plagiarised at all [1].

Now if all of this sounds a little murky, it is because it is. Even the most cursory overview of scholarship on the Rowley (Chatterton) or Ossian controversies will point to how internecine these issues were in our period. But add magazines into the mix and it gets a whole lot muddier still.

Histories of copyright and plagiarism offer fascinating context for thinking about the status of unacknowledged, repurposed content in periodicals such as the Lady’s Magazine. Ultimately, however, their general failure to address periodicals as a genre leaves important questions hanging: How were eighteenth-century and Romantic periodicals understood to function in terms of copyright law? Were they, as the magazines themselves often claimed, a special case? And if so, is it at all appropriate to use a word like plagiarism in the same breath as periodicals.

Returning to Mazzeo’s helpful definition for a moment, I can’t really bring myself to do so for several reasons, only some of which I have space to elaborate below.

The first is the difficulty we sometimes experience in trying to establish the original iteration of a work we suspect has been published before it appeared in the Lady’s Magazine. In this digital age, it is, of course, much easier to find previously printed sources for magazine content through search engines or online databases than was once the case. (Note to self: remember, though, that the internet should not be mistaken for a complete archive.) Sometimes the answers obtained from such sources are only partly helpful, however. Often magazine contributions appeared simultaneously or near simultaneously in multiple periodicals. Finding out that a poem appeared in the Lady’s Magazine and the Town and Country (another Robinson publication) or The Gentleman’s Magazine (not a Robinson publication) in the same month tells us nothing about the originality of the work or what its author’s intentions for it were.

Then there is the imaginativeness that needs to be deployed to find some contributions we suspect might not be original to the magazine. Koenraad has already written about this and I hope will do so more as the project develops, but the inventiveness he shows in digitally searching for textual originals (omitting character names, as sometimes these were changed, or finding synonyms for keywords) knows no bounds. But it also leaves me pondering: if a text, while essentially the same in terms of argument, structure, subject or narrative, has names changed, parts excised or keywords altered, can it legitimately be called a plagiarism? Isn’t this a rewritten work. At the very least, while such changes may have be made wilfully, the ‘improvements’ made to the original certainly seem to leave its ‘author’ immune to the accusation of culpable plagiarism as defined by Mazzeo.

Another reservation I have about the P-word when talking about magazines from this period is cultural. For one thing, we know that eighteenth-century novels constantly reworked each others plots, often relying upon readers’ recognition of stock character types or conventional names or plot devices to raise or subvert expectations that would excite readers’ sympathy, fear or horror. For another, intertextual referencing or allusion are commonplace in all textual genres throughout the period, and there was clearly a huge degree of tolerance for (cough-cough) variations in accuracy of citation.

But periodicals are, nonetheless, something of a special case. People reading eighteenth-century and Romantic magazines did not expect to be reading wholly original content. Nor did contributors to magazines always feel they had to be original in their submissions. A common type of submission to the Lady’s Magazine is what I refer to as the commonplace: of a reader who reads a book, the title of which they may or may not remember or disclose, or which they have found in another, sometimes unacknowledged publication, but they find particularly noteworthy for whatever reason and from which they excerpt extracts they send to the magazine for republication.

There are at least two possible ways of reading this practice. It could, and in some cases likely often was, a ruse, whereby staff writers used this convention to recycle already published material in a way that didn’t seem culpably plagiaristic. At other times, these may well have been genuine instances of readers wanting to share with others works they found particularly notable, relevant, or interesting and, in the process, implicitly to declare their own readerly credentials. These kinds of submissions are ones that I would like to return to in a future post. In this context, though, they speak to the widely perceived acceptability of repurposed content, repackaged by a third party, in contemporary magazines.

But I would go further than this. Generically, periodicals (especially magazines as opposed to, say, the essay-periodical) don’t work in the same way as other genres. If, as David Mazella has recently explained, the magazine is a genre, then it is a unique one, one that ‘by definition consumes other, smaller genres or microgenres and presents a temporally segmented selection of content on a regular basis’ [2]. When an extract from a previously published work – a biography, an anecdote, a meditation on good conduct – appear in extracted form in a magazine like the Lady’s, it becomes something different from what it previously was. Whether it is ‘improved’ or not by its reiteration is a judgement call about which we might not all agree. Even so, it is surely true that the status of the extract, by virtue of its remediation within the magazine genre, is fundamentally different than in its original format even if its wording is substantively or even exactly the same. The Vindication of the Rights of Woman that appears in the Lady’s Magazine, a magazine that also published acknowledged extracts from works of James Fordyce, Dr. Gregory and Jean Jacques-Rousseau that Wollstonecraft held were paradigmatic of the degraded state of woman, is not the same work that Wollstonecraft penned. It reads differently.

These, and many other issues besides, have been discussed at length by the three of us in recent weeks as we establish our terminology for indicating repurposed / recycled / remediated / plagiarised material. It’s led to some lively debate and an extended conversation with some of our followers on Twitter on the @ladysmagazineproject feed and on my own personal Twitter feed (@jenniebatchelor).

Our resolution, for now at least, is to opt for the phrasing ‘previously published’ to divest from our own terminology the legal and moral implications of the term plagiarism, which may well be anachronistic for our period, especially when referring to periodicals. The solution might seem cowardly or non-committal, but I don’t see it that way. Instead, I see it as a pragmatic, historically sensitive stance on an important issue. The question of why, I think, it matters so much is one I will return to in my next blog post in a few weeks’ time.

As always, I’d love to know your thoughts on this!

Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent

[1] Tilar J. Mazzeo, Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

[2] I am very grateful to Professor Mazella for sharing his paper ‘Temporality, Microgenres, Authorship and The Lady’s Magazine’, which was delivered at the ASECS 2015 conference.