LM XL (Aug 1799). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

As Koenraad noted on the blog last week, one of the (many) frustrations involved in working on the Lady’s Magazine is the lack of a publisher archive for the Robinson family who published it. Various correspondence between George Robinson Sr (1736-1801) and many of his authors, including Phebe Gibbes, William Godwin and Charlotte Smith, has survived, of course. Then there is the Manchester City Library Robinson ledger archive we featured last week. But, sadly, the sum of these documents seems to be pretty much all that is extant.

We live in hopes that someday, somewhere we will find an equivalent to John Nichols’s meticulously documented index to the Gentleman’s Magazine (1821) which will explain everything we want to know and more about the day-to-day running of the Lady’s Magazine or even the Robinsons’ concern more generally. We may be waiting a rather long time, however.

Conventional wisdom has it that one of the reasons why there might be little by way of a Robinson archive is the devastating fire that broke out on 2 February 1803 at the Falcon-court, Fleet-Street, printing office, warehouses and home of the publishers’ printer, Samuel Hamilton. According to the New Annual Register for 1803, ‘in the short space of two hours’ the fire, which was ‘supposed to have arisen from the carelessness of a boy’, ‘entirely consumed the whole of [Hamilton’s] valuable and extensive premises’. No one was killed, mercifully, but the ‘loss of property (printed books)’ was noted to be ‘particularly severe’.

Conventional wisdom has it that one of the reasons why there might be little by way of a Robinson archive is the devastating fire that broke out on 2 February 1803 at the Falcon-court, Fleet-Street, printing office, warehouses and home of the publishers’ printer, Samuel Hamilton. According to the New Annual Register for 1803, ‘in the short space of two hours’ the fire, which was ‘supposed to have arisen from the carelessness of a boy’, ‘entirely consumed the whole of [Hamilton’s] valuable and extensive premises’. No one was killed, mercifully, but the ‘loss of property (printed books)’ was noted to be ‘particularly severe’.

The loss was all the worse because Hamilton’s insurance had at least partly lapsed. Although the ‘manuscripts of the most important works’ were claimed to have been saved, including ‘those of the CRITICAL REVIEW, and […] the Lady’s Magazine’, which were said to be with their respective ‘editors’, many others were lost (24: 26). (In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that the New Annual Register was published by G. and J. Robinson and printed by one S. Hamilton.) Amongst the greatest losses was ‘part of the works of the late learned and much respected rev. Gilbert Wakefield’, the thousand pounds insurance on which had just expired (24: 26). Publisher bias or not, this was a substantial loss.

The fire was clearly devastating for Hamilton, who soon afterwards moved his business to Weybridge. It was also a real blow for the Robinsons. The Robinsons and Hamiltons’ connection preceded the New Annual Register collaboration by a long way. The Edinburgh printer and publisher Archibald Hamilton Sr (1719-93), Samuel’s grandfather, and Archibald Sr’s son, Archibald Jr (Samuel’s father), both owned a sixth share in the Lady’s Magazine from 1770 as well as in the Town and Country Magazine (another Robinson concern). Samuel and his brother (a third Archibald) inherited their father and grandfather’s business and Samuel appeared on the title-page of the Lady’s Magazine as its printer from August 1799. George Robinson Jr (d. 1811) and his uncle John (1753-1813) invested in Samuel’s business and the financial loss the fire occasioned them is often held to be largely responsible for the Robinsons’ bankruptcy on 8 December 1804. The fact that the firm (and indeed the Lady’s Magazine) survived this difficult time by many years is testament to the talents of these resourceful and well-connected men [1].

It’s not at all clear to me why the warehouse fire is often assumed to account for the lack of a more complete Robinson archive, however. As the New Annual Register makes clear, only some of the magazine’s contents were even in the printing house at the time as the majority of manuscripts and presumably associated correspondence were held by the magazine’s editors. As so often in our research, the shards of evidence we find about the day-to-day administration of the magazine pose more questions than they answer. Except that the coverage of the fire and the magazine’s references to it in its own pages do offer some useful research leads and insights.

LM XXXIV (1803). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

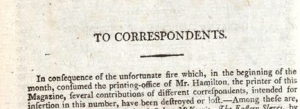

The ‘unfortunate’ fire is first mentioned in the magazine in the February 1803 issue, which likely appeared in early March. Contrary to the report in the New Annual Register, the magazine’s editor noted that the fire consumed ‘several contributions of different correspondents’, but seemingly only those intended for ‘insertion in this [month’s] number’. The magazine only mentioned three of these by name: the continuation of the picaresque novel-cum-memoir, the Life of Robert McKenzie; E. W.’s The Eastern Slaves; and the month’s instalment of John Webb’s serial poetic reflections, A Morning’s Walk in February. These correspondents were asked to ‘send other copies’ as soon as possible’ (LM XXXIV [Feb 1803]: ‘To our Correspondents’).

John Webb wins the prize for the speediest response. His ‘Morning’s Walk for February’ was re-sent in time to appear alongside the next instalment in the March 1803 issue, while E. W.’s narrative appeared under the altered title ‘The Slaves – an Eastern Tale’ in April. Robert McKenzie did not resume until June, but then again its skittish author was not the most reliable of contributors at the best of times.

When I have relayed this information in talks about the Lady’s some audience members have been surprised that authors would have been able to produce multiple copies of their works at such short notice in a pre-digital age. But of course in a pre-digital age, dependent on unreliable postal services, magazine editors who almost routinely mislaid items submitted to them and candles that weren’t counteracted by smoke alarms, such practices were only prudent. What interests me more about this anecdote is its research potential. If, as we know, correspondents kept copies of their submissions in case they were required to re-send them or because they opted to send them somewhere else if their efforts were rejected by their first-choice outlet, then might there not be a chance that we might find some of these manuscripts one day?

Another insight comes from a series of references to the fire in 1804 that accompany some of the magazine’s serial fiction. The original fiction published in the magazine has often, and in our view often erroneously, been given short shrift by scholars who dismiss all amateur contributions as unfit for publication elsewhere. Such a view depends on dismissing the inconvenient fact that some of this fiction (such as A. Kendall’s Derwent Priory [1796-97] or the sketches that became Mary Russell Mitford’s Our Village [1824]) was published in volume form after publication in the Lady’s and wore its origins as magazine fiction loudly. The process rarely worked the other way round. The Lady’s frequently published extended extracts of works of history, philosophy or travel writing, but usually only reprinted novels that had been previously published elsewhere if they were new translations of foreign works (such as the magazine’s long-running translation of Madame de Genlis’ Adelaide and Theodore (1784-89). The copyright laws surrounding novels evidently engaged periodical editors’ attentions much more than those surrounding other genres.

LM XXXV (March 1804). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

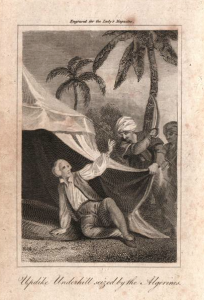

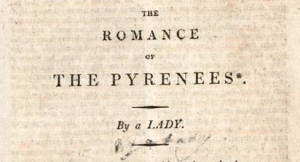

In 1804, though, we find two exceptions to the general rule governing the non-reprinting of previously published fiction. In both instances, the Hamilton fire was the occasion for the deviation from business as usual, and copyright infringement was, in any case, no issue. In January of that year, the magazine began its serialisation of Royall Tyler’s The Algerine Captive; or the Life and Adventures of Doctor Updike Underhill, Six Years a Prisoner among the Algerines. (Tyler’s fiction had been only the second American novel to appear under a British imprint when the forward-thinking Robinsons published it in two volumes in 1802.) This was followed, in February, by the first instalment of The Romance of the Pyrenees, a novel published anonymously in 1803, and later attributed to Catherine Cuthbertson, although at least one reader of the later French translation (1809) wrongly assumed its author was Ann Radcliffe. Both were originally published by the Robinsons and printed by Hamilton. What these novels also had in common was their near destruction by the fire, which seems to have consumed ‘nearly the whole of the impression’ of both runs left in the printer’s warehouse (LM XXXV [Jan 1804]: 37). Evidently lacking in confidence that a second impression of either would be financially viable, the novels were repackaged, with chapter breaks reorganised, to fill the pages of the Lady’s Magazine.

LM XXXV (Feb 1804): 87. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

This was more than a gesture of pragmatism or an opportunistic attempt to get two novels off their hands without throwing good money after bad. Throughout its history, the magazine was canny about using its popularity and reach as a way of opening up audiences for other of its published works, even while it promised reams of original essays, fiction, poetry and other works that could be found nowhere else. The publication of The Algerine Captive and The Romance of the Pyrenees was just the most self-conscious example of this decades-long practice.

And it clearly worked. Cuthbertson’s career proceeded outside the magazine, and The Romance of the Pyrenees would go through a handful of further editions (its fifth was published in 1822) as well as spawning the aforementioned French translation [2]. Gillian Hughes has recently remarked that this move added some ‘desirable fictional sparkle to a magazine that was by then lagging behind readerly expectations’ [3]. I remain unconvinced by Hughes’s argument about readers’ dissatisfaction with the fictional content of the magazine. The periodical, at least, did not register such dissatisfaction for another decade or more. But telling Lady’s Magazine readers that they were reading a novel that was ‘no longer to be procured’ outside its pages was clearly a shrewd and effective marketing strategy (LM XXXV [Apr 1804]: 87).

Such glimmers of insight may not seem much. But in the absence of an archive for the Robinsons or, better still, for the Lady’s Magazine more specifically, they offer us important information about the publishers’ network, which along with other evidence we are slowly piecing together, might well provide important leads in identifying contributors to the periodical. Additionally, they indirectly shed light on the murky question of how the magazine interpreted copyright law (clearly differently for novels than for other genres) and suggests some of the ways in which the Robinsons understood the Lady’s to fit into their wider publishing concern. When you’re working in the dark, even something as destructive as a fire, it turns out, can be productive in its own way.

Notes

[1] G. E. Bentley jun., ‘Robinson family (per. 1764–1830)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/74586, accessed 6 July 2015]; and Barbara Laning Fitzpatrick, ‘Hamilton, Archibald (1719–1793)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/65018, accessed 6 July 2015]

[2] F. W. Bateson, ed., The Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, 1800-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), p. 392.

[3] Gillian Hughes, ‘Fiction in the Magazines’, in The Oxford History of the Novel in English, Vol. 2, English and British Fiction, 1750-1820, ed. Peter Garside and Karen O’Brien (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 472.

Dr Jennie Batchelor

School of English

University of Kent