‘What Did You Do In The War?’ is the title of Clarkson Rose’s comic song written in 1919, and follows the experience of a father recounting to his son what he did during the Great War. The song addresses various themes and elements of life that contemporaries of Clarkson Rose would have been familiar with and able to relate to. These include the experience of food controls and the rise of prices of food items like ‘marmalade and jam’, as well as the joining up of men to fight in the Great War, such as Clarkson Rose’s ‘Comic singer’, who joined the Army Service Corps. The experiences of women are also addressed, who, like the boy’s mother, ‘used to sew some socks for all the soldiers out in France’, as well as those who undertook employment, working in munitions factories for example.

Clarkson Rose’s comic song, however, is not the only item within the David Drummond Pantomime collection to epitomise what life was like during the First World War, particularly with regard to the experience of soldiers at the front. What we also see within this collection is the familiarity with and exposure that soldiers had to pantomime during the First World War, helping us to better recognise the key role of pantomime and performance in boosting morale during the First World War. Examining these materials strengthens our understanding about how both watching and participating within pantomime was part of what troops did during the Great War.

Theatre and performance were vital in distracting servicemen from the horrors of the theatre of war, not just on the Western Front but in other areas too, notably the Macedonian Front. This blog post specifically shows examples of programmes for pantomimes performed in Salonika, now modern-day Thessaloniki, which was also ravaged by the brutality of war. This blog post also demonstrates how what was happening during the First World War was incorporated into pantomime and provides a commentary on this period of history.

Pantomime and Performance on the Macedonian Front: Christmas in Salonika

One of the things that is particularly interesting about the material found within the David Drummond Pantomime collection that relates to the First World War, is the spotlight this collection places on enjoyment and entertainment beyond the Western Front. Many of us will have heard a lot about the Western Front, with the focus on what occurred along the French and Belgian border being ubiquitous in popular culture. It seems, however, that the other areas in which fighting occurred is less well-known and it must be remembered that along the Macedonian front, British troops were part of a multi-national Allied force that fought against the Bulgarians and those who supported them in the Balkans, including Turkish forces, German forces, and Austro-Hungarian forces.

Various companies performed pantomimes during the First World War and the examples of entertainment at Salonika within the David Drummond Pantomime collection displays the involvement of different companies. For example, the following souvenir edition for the pantomime Dick Whittington shows that a performance of this pantomime was produced by members of the 85th Field Ambulance and took place in Salonika in December 1915.

‘Foreword’ written by Major C J Briggs in the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington performed at Salonika during Christmas 1915. The ‘Foreword’ was written at Headquarters of the 28th Division on 24th February 1969 and features the Major General’s signature.

The ‘Foreword’ written by the Major General C J Briggs is particularly revealing and emphasises just how important pantomime was for raising optimism and for ‘all hearts [to be] gladdened’. The author of the souvenir edition, Frank Kenchington, goes one step further than the Major General. He stressed that in being asked by the Major General that a performance of Dick Whittington should be performed for ‘the whole of the troops in the Division’, those who contributed to organising this pantomime had been ‘given the privilege of their share, in their small way, to enliven the dull and uninspiring monotony of a winter in the mountains of Greece’. As well as entertainment, undertaking this performance was also a means of commemoration, of ‘[reviving] memories of many an old friend and many a half-forgotten chapter in this Campaign’.

The souvenir edition of Dick Whittington also gives an insight into the individuals that made up the company of actors, who provided their comrades with entertainment, amusement, and delight.

Synopsis of scenery, list of creative team, and cast members in the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington, written by Frank Kenchington, and performed at Salonika during Christmas 1915.

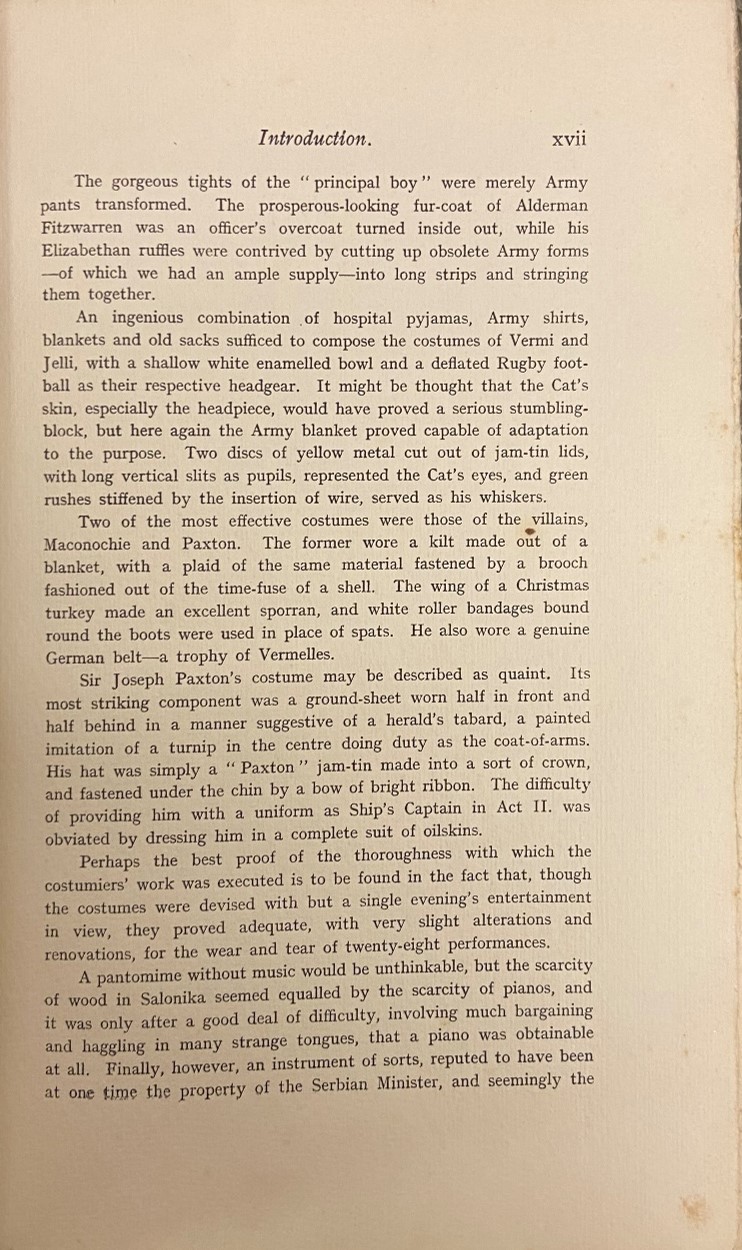

Troops used whatever they had to hand to co-ordinate and craft their pantomime, and this souvenir edition shows just what materials were used to make costumes for this performance of Dick Whittington.

Extract from the ‘Introduction’ of the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington by Frank Kenchington. Performed in Salonika during Christmas 1915.

As we see from the ‘Introduction’ to this souvenir edition, army pants became the tights of the Principal Boy and ‘hospital pyjamas, Army shirts, blankets and old sacks’, as well as ‘a deflated Rugby football’ were used for costumes. Parts of everyday army life and a typical soldier’s uniform were transformed to make the pantomime performance happen. Even haggling was involved and from the above we see the efforts that were made to ensure there was music within the pantomime.

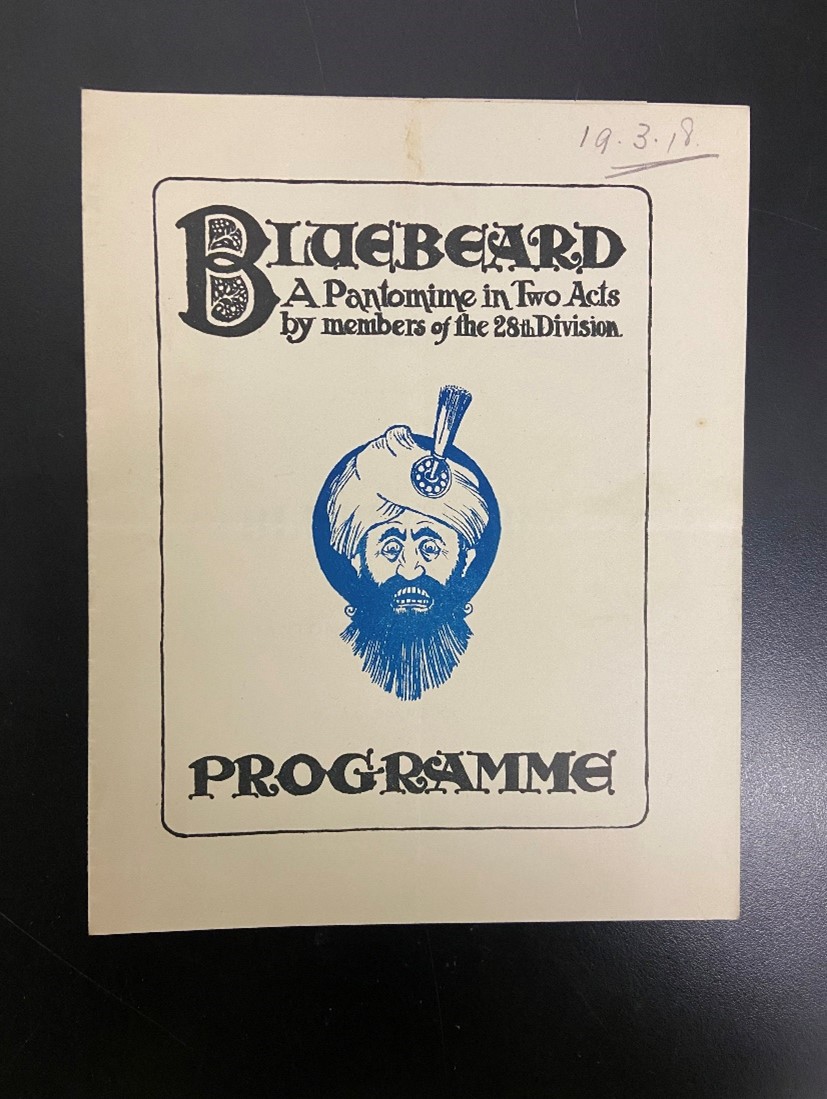

Pantomimes continued on to the final year of the First World War and the below programme for a performance of Bluebeard, whilst slightly out of season, provides further evidence that entertainment and pantomime was a regular feature of Christmas for troops fighting during the First World War. As you can see from the annotation made on the top right-hand corner, this version of the pantomime Bluebeard was written by Private G G Horrocks and was performed by members of the 28th Division in March 1918.

Front cover of the programme for the pantomime Bluebeard by Private G G Horrocks, performed in Salonika in March 1918 by the 28th Division.

Like the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington, this programme for the pantomime Bluebeard reflects what life was like during Christmas in Salonika. It shows the involvement and interaction that soldiers had with the art of pantomime to put on a show for their brothers-in-arms.

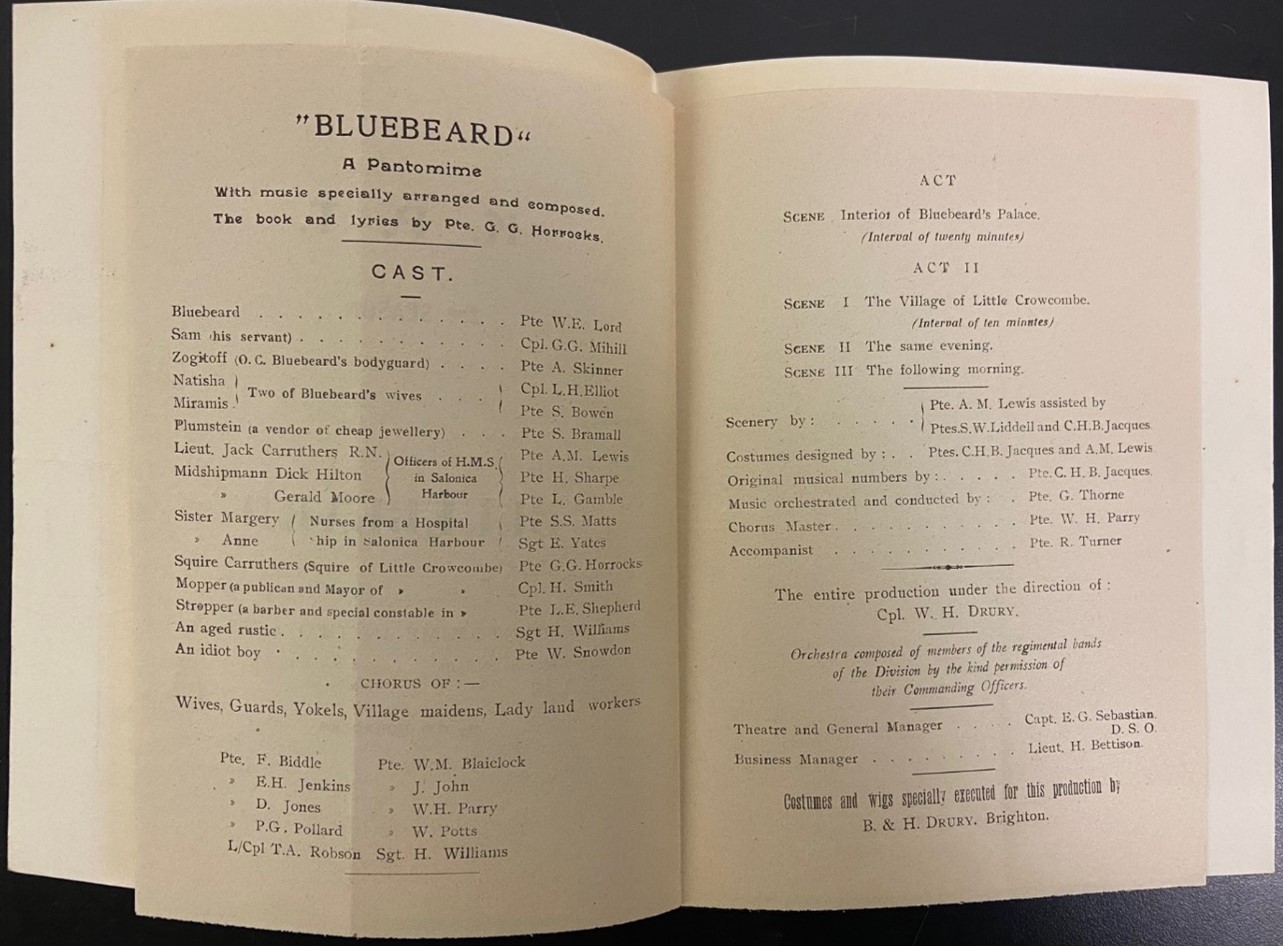

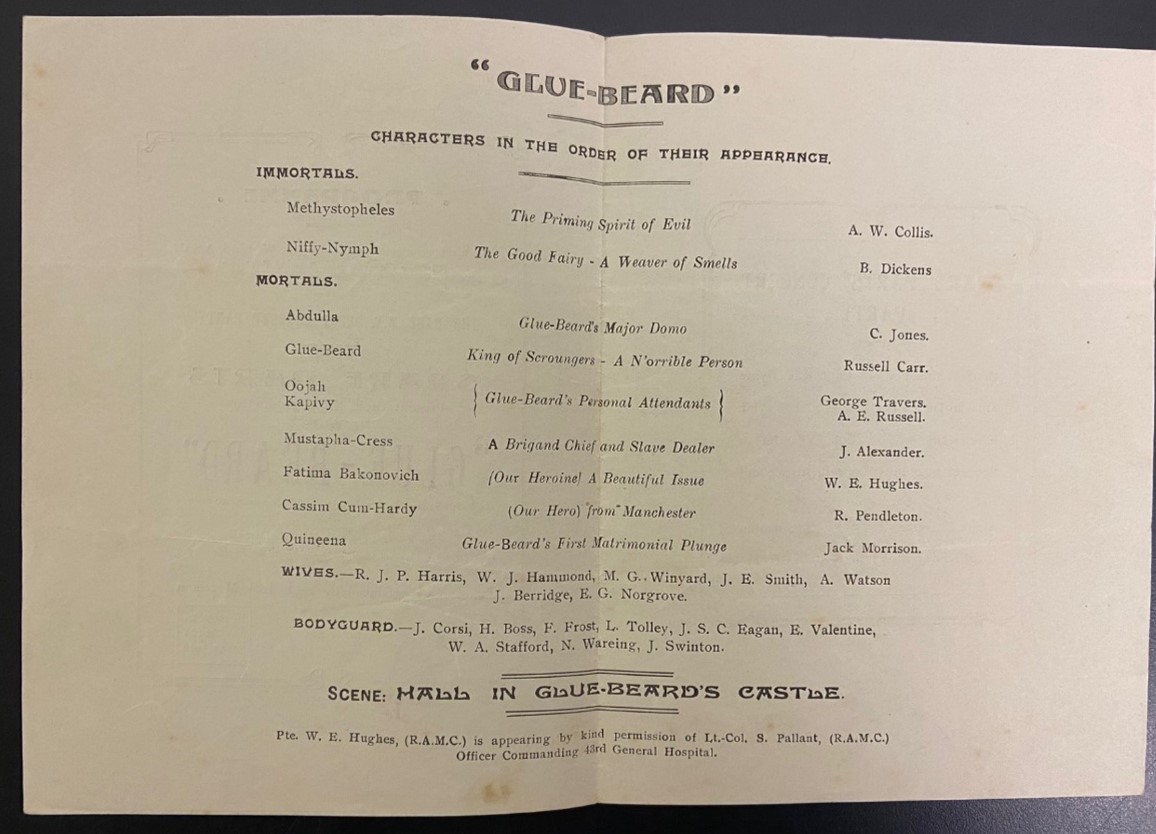

Pages listing the cast and creative team for the pantomime Bluebeard by Private G G Horrocks, performed in Salonika in March 1918 by the 28th Division.

A full cast list is included, showing a range of ranks – Private, Corporal, and Sergeant – within the 28th Division, as well as the creative team, who were responsible for creating costumes and the scenery, and an outline of the acts. The programme even showcases who was responsible for crafting the musical numbers and who played the music, informing audiences that the ‘Orchestra was composed of the regimental bands of the Division by the kind permission of their Commanding Officers’.

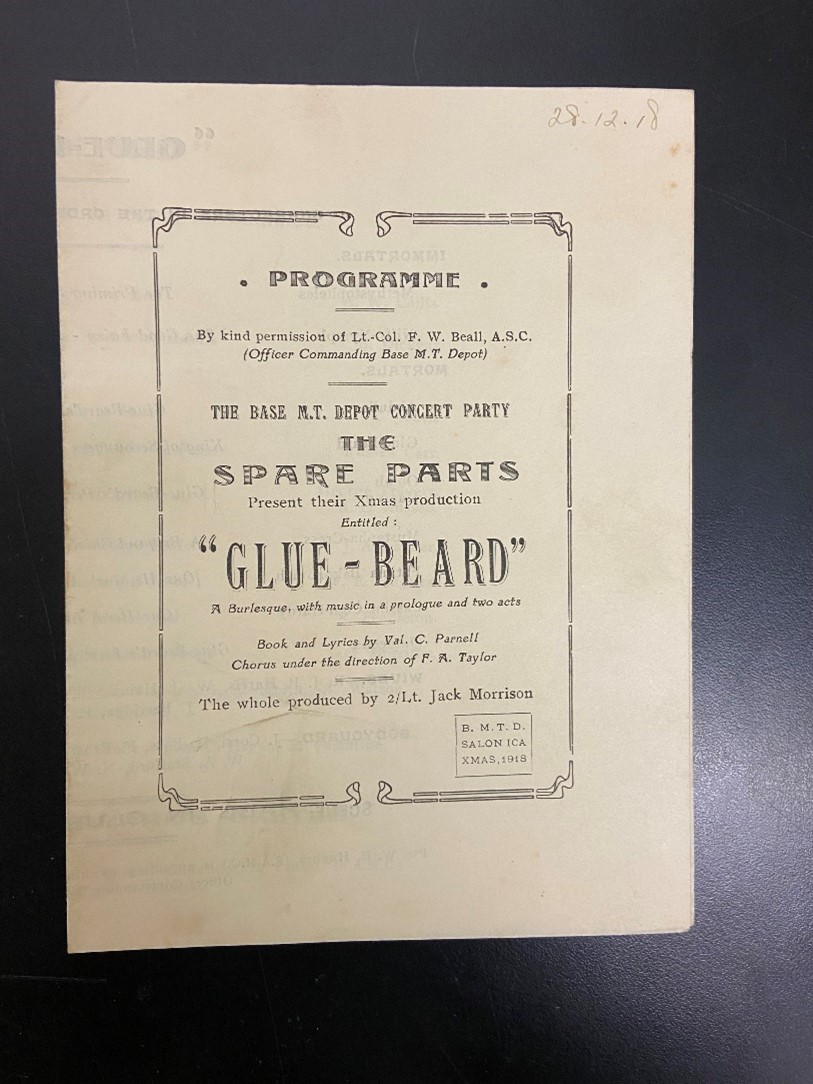

The programme shown below for the Christmas production “Glue-Beard”, further demonstrates the enduring power of pantomime at the very end of 1918, even after the Armistice had been signed on 29th September 1918 at the General Headquarters of the Allied Army of the Orient at Salonika. This Armistice was signed between the Allies and Bulgaria, and came into force at midday on 30th September 1918.

Programme for a performance of “Glue-Beard”, A burlesque, with music in a prologue and two acts. Performed at the Base M.T Depot Concert Party in Salonica during Christmas 1918. The production was presented by The Spare Parts.

Despite the ceasefire and the signing of the Armistice, troops continued to stay in Salonika. During the First World War, the British army that was in Salonika was known as the British Salonika Army. Whilst this was disbanded in November 1918, the units that remained were renamed as the Army of the Black Sea and, as seen from the above programme, those who stayed in Salonika continued the tradition of performing pantomime as entertainment for troops at Christmas. The performance was produced by Second Lieutenant Jack Morrison and was presented by the Spare Parts at the Base M T Depot Concert Party, ‘by the kind permission’ of the Lieutenant-Colonel F W Beall, A S C. Like the souvenir edition of Dick Whittington and the programme for Bluebeard, we can see which soldiers starred in the performance and the roles that they played.

Cast list for a performance of “Glue-Beard”, A burlesque, with music in a prologue and two acts. Performed at the Base M.T Depot Concert Party in Salonica during Christmas 1918. The production was presented by The Spare Parts.

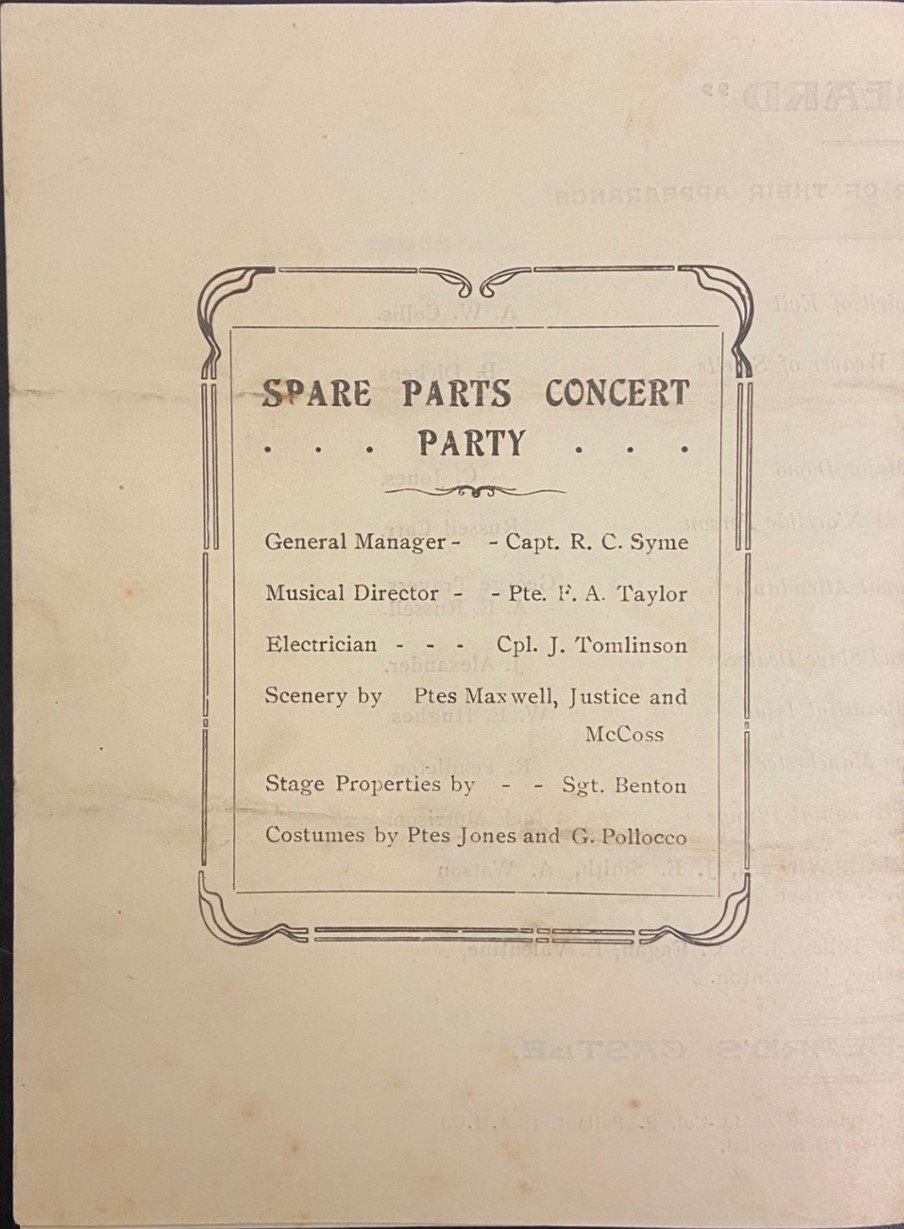

Like the above items, the performance of pantomime seems to have been taken quite seriously and we can see that the professional positions of General Manager, Musical Director, Electrician, as well as individuals who took on the roles the responsibility of scenery design, costume design, and organising stage properties (props), was undertaken by the following soldiers: Captain R C Syme; Private F A Taylor; Corporal J Tomlinson; Privates Maxwell, Justice and McCoss; Sergeant Benton; and Privates Jones and G Pollocco.

Back cover of the programme for a performance of “Glue-Beard”, A burlesque, with music in a prologue and two acts. Listed are the roles of General Manager, undertaken by Captain R C Syme; Musical Director, undertaken by Private F A Taylor; Electrician, undertaken by Corporal J Tomlinson; Scenery by Privates Maxwell, Justice, and McCoss; Stage Properties by Sergeant Benton; and Costumes by Privates Jones and G Pollocco. Performed at the Base M.T Depot Concert Party in Salonica during Christmas 1918. The production was presented by The Spare Parts.

The Second World War and the Entertainments National Service Association

The immense impact that pantomime and entertainment had on morale during times of hardship and destruction is further reinforced by the creation of the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) upon the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Created by Basil Dean and Leslie Hensen, both prominent figures in the entertainment industry who had been active in organising theatre and performance during the First World War, ENSA was an organisation that was founded to specifically provide enjoyment for troops and operated as part of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (N.A.A.F.I).

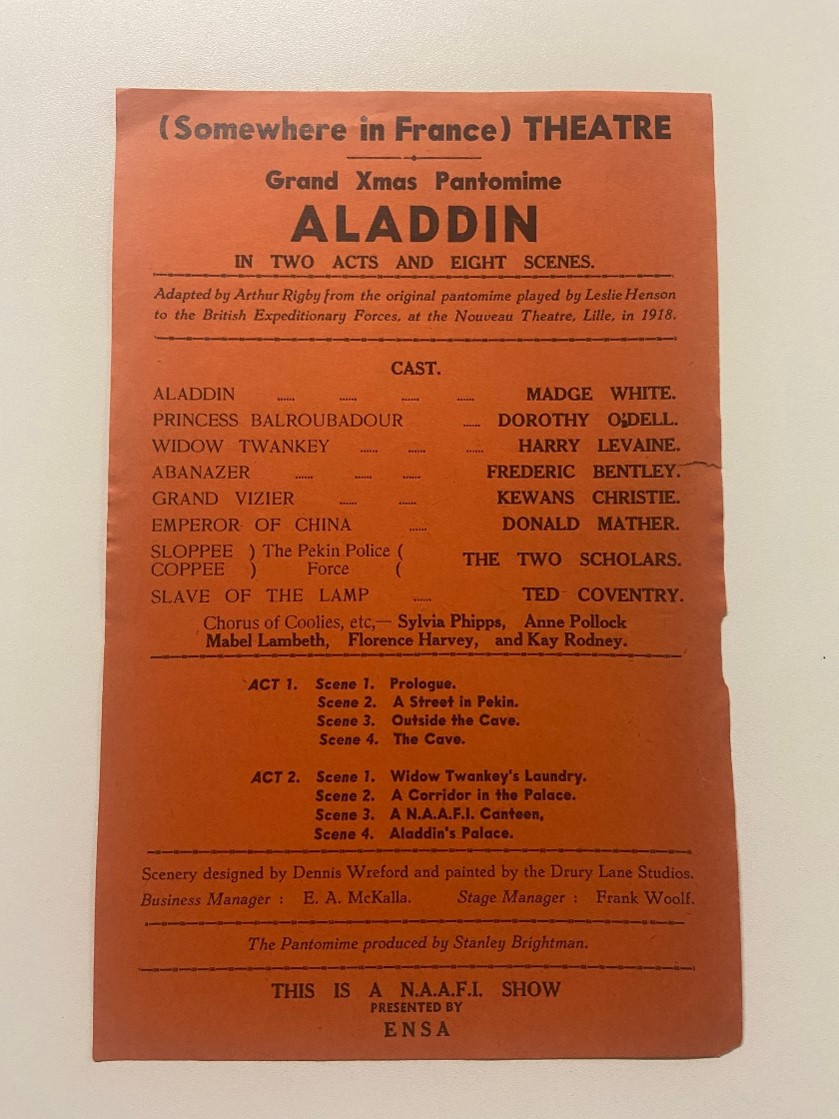

ENSA and N.A.A.F.I’s role in continuing the delivery of pantomime to troops at Christmas time is seen in the flyer below. This is a flyer for the ‘Grand XMAS Pantomime’ Aladdin at the (Somewhere in France) Theatre. The flyer lists the cast and provides a breakdown of the acts and scenes. They spared no effort, incorporating scenery designs by Dennis Wreford that were painted by the Drury Lane Studios, and had a proper Business Manager, E A McKalla, Stage Manager, Frank Woolf, and Producer, Stanley Brightman, involved.

Flyer for a performance of the pantomime Aladdin at (Somewhere in France) Theatre. This was performed at Christmas time at some point during the Second World War and was organised by ENSA and N.A.A.F.I. Some terms used in this record reflect contemporary attitudes and language used during the period. All such terms are used in the interest of historical accuracy, as altering them would risk falsifying the historical record. This language does not reflect the views or opinions of the University of Kent, Special Collections & Archives or our staff.

Interestingly, the flyer makes a direct link to ENSA’s co-founder, Leslie Hensen, demonstrating the key role he played in delivering entertainment during the First World War. The flyer informs audiences that this performance of Aladdin was adapted by Arthur Rigby from the original played by Leslie Hensen to the British Expeditionary Forces at the Nouveau Theatre in Lille during 1918. It’s a great example of the enduring legacy of entertainment during both World Wars and the importance of entertainment as part of the war effort.

Conclusion

Not only were troops fighting along the frontline but, from the above examples, we see that time was dedicated to providing entertainment and enjoyment for their comrades. Soldiers actively took part within the performance as key characters, as well as ensuring that materials needed to set the staging and deliver the pantomime were gathered and made. Clarkson Rose’s comic song ‘What Did You Do In The War?’ is an excellent reminder and social commentary on post-war feeling and the various experiences that people, particularly on the Home Front, had during the First World War but, also, it is important to remember other elements of life and the solace that troops found in a moment of profound delight, where the troubles of the Great War could be forgotten.