In the film A Glimpse of Teenage Life in Ancient Rome, the Secundus boys take a trip to the Forum of Augustus to see statues of Rome’s famous warriors. These included the Trojan hero Aeneas, Romulus the founder of Rome, the great generals of the Republic and, of course, Augustus himself. But what did Lucius and his brother actually see as they strolled through the shady porticoes? If the statues set up in the forum were made of marble — and there is a bit of debate about this, some say they were made of bronze — then, unlike what you might expect, the boys would not have been faced with a sea of gleaming white figures.

Exercise: Click here to find out more about the statues in the Forum of Augustus. If there are some names you do not recognise, bolster your knowledge by doing a search to discover how they made their name.

Back in the Renaissance it was believed that Classical sculpture was pure, gleaming white. But in fact there is now an abundance of evidence that reveals ancient statues were painted in vibrant and sometimes even gaudy colours.

Looking for colour

Cult statues, portraits and even garden statues were painted to enhance their appearance. The hair, eyes and lips as well as clothing were often picked out to receive this special treatment. Although today the paint is often faded, there are examples where traces of pigment can still be seen.

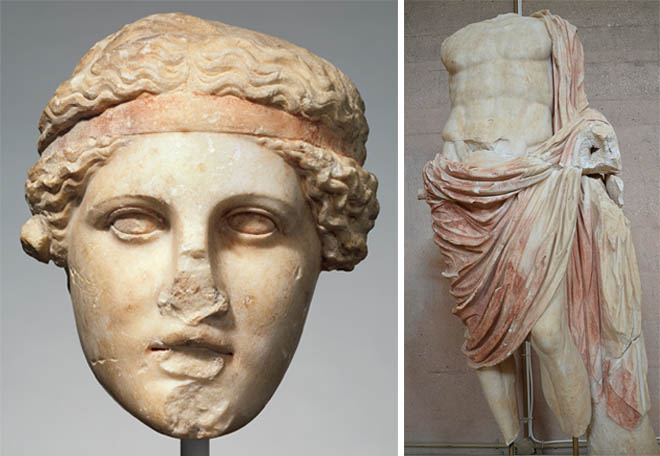

Left: Marble head of a deity wearing a Dionysiac fillet, Roman, ca. A.D.14–68. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Roman statue from the theatre of Corinth, 10-35 AD, Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth, Greece. Image: Carole Raddato via commons.wikimedia.org.

For example, this marble head depicting a deity (above) still retains much of its red colouring. Originally, her hair was gilded over a yellow background and then embellished with red paint. Her lips, eyes, eyebrows and eyelashes were also defined in red. You can see another example of a painted head here. The clip shows the excavation and cleaning of a bust of an Amazon warrior woman found in Herculaneum. In the statue from Corinth (above), the painter has picked out the finely carved drapery, applying colour to enhance its appearance.

Relief showing the god Mithras slaughtering a bull. End of the 3rd century AD, Baths of Diocletian Museum, Rome. Image: Paula Lock.

Another colourful example is this marble relief of the god Mithras, which not only retains its paint but also some gilding. Click here to see another example of the use of gilding, this time applied to a statue of the Roman Goddess Venus, which was found in Pompeii.

Fresco showing a statue of Mars. From the House of Venus in the Shell, Pompeii. Image: Paula Lock.

As well as these slightly faded examples of painted sculpture, a fresco from Pompeii shows us what a statue — presumably in peak condition — might have looked like. The god Mars is pictured standing on a plinth, his pale skin tone contrasts with the hair and facial features that are picked out in paint. The additional flourish of a red painted cloak completes this rather life-like depiction. The colours used for the statue are subtle against the backdrop of this brightly coloured garden fresco, quite different from the reconstructions below.

The written word

As well as the archaeological remains, the ancient literature suggests that the painting of sculpture was a common practice in antiquity. For example, there is a rather nice anecdote recorded by the Roman writer Pliny, who says that when Praxiteles (a Greek artist famous for his marble sculpture) was asked

‘which of all his works in marble he was the best pleased, made answer, “Those to which Nicias has set his hand,” so highly did he esteem the colouring of that artist’.

Plin., HN, 35.133

Plato’s Republic 4.420c also emphasises the importance of colour to perfect the finish of statues. However, perhaps one of the most revealing passages comes from the satirist, Lucian, who clearly highlights the importance of finishing a statue by embellishing it with colour. Read the passage here (7-8).

Exercise: What parts of the statue were to be enhanced with pigments? What colours were suggested for the greatest affect?

Work in progress

As well as the statues themselves, we can also get a glimpse of the painters at work in their studios. A Carnelian ring stone, for example, shows a man seated in front of a female bust. In one hand he holds a brush and delicately paints the hair, while in his other hand he holds what appears to be a palette.

Left: A Carnelian ring stone showing an artist at work. Roman, ca. 1st –3rd century A.D. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Terracotta column-krater showing a painter at work. Greek, South Italian, Apulian, ca. 360–350 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This Greek vase — used for mixing water and wine — reveals the secrets of the painting process. The vase — depicting an artist at work on a statue of Herakles — shows two steps of the painting process. First, the pigments are heated and mixed. Then the artist uses rods — which are kept warm in a charcoal brazier by an assistant — to paint the statue.

True colours?

Modern research has used various scientific methods (raking light, as well as UV, infrared and X-ray spectroscopy) to reveal what pigments originally adorned sculptures. The results of this work have made it possible to reconstruct statues painted in their true colours, so we can get a clearer picture of what the ancients saw when they gazed upon these works of art. This clip shows some of the processes involved in bringing a piece of sculpture back to its original glory.

Left and top right: Painted replica of the Augustus Prima Porta statue. Below right: Portrait bust of Caligula. From the Gods in Colour exhibition. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Images: Paula Lock.

This statue of Augustus shows how colour transforms the sculpture with its bright and vivid tones. Again the hair and facial features are picked out for enhancement. But it is the various colours and detailing on the breastplate and the rich red cinnabar used for his cloak that particularly draw the eye. You can find out more about this statue and the different interpretations of its original colour here. The cast of a marble head of Caligula is equally striking with its original colours restored.

These reconstructions come from an exhibition called ‘Gods In Colour: Painted Sculpture in Antiquity’. Here are some of the other statues that were included in the exhibition. Although it is generally accepted that Greco-Roman statuary was painted, there is still some debate as to whether the colours were quite so garish or whether the final effect was a little more subtle. What do you think?

Reconstructions from the Gods in Colour exhibition. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Images: Paula Lock.

So, to answer the question posed at the start of this blog, what the Secundus boys saw as they travelled through the Forum of Augustus would have been marble statues with zingingly colourful paint, the likes of which today might lead us to don our sunglasses!

Before and after, which do you prefer? Image: TED ED.

Before and after, which do you prefer? Image: TED ED.

Exercise: If you’re feeling creative why not have a go at restoring the colours on this marble bust of a Roman woman. If you don’t have access to Photoshop you can go old school and get your paint box out!

Bibliography and further reading

Bradley, M. “Art and the senses: the artistry of bodies, stages and cities in the Greco-Roman world”. In: A Cultural History of the Senses in Antiquity I, edited by J.P. Toner, 183-208. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Bradley, Mark. Colour and Meaning in Ancient Rome. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Friedland, Elise A., Melanie Grunow Sobocinski, and Elaine K. Gazda, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Roman Sculpture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Nicholson, Wornum, Ralph, Colores (Smith’s Dictionary, 1875), Article on Roman pigments via Lacus Curtius.

Tracking Colour: The polychromy of Greek and Roman sculpture in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Preliminary Reports 1-5.

Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Jerome Lectures, 16th ser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988. See p188-192 for a description of the scene on Augustus’ breastplate.