This month’s post has been written by Philip Smither, a third-year PhD student in Classics and Archaeology at the University of Kent.

In the latter half of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, the field of archaeology was marked by a striking number of large-scale and famous excavations. At the same time as Howard Carter was excavating in the Valley of the Kings, the newly-appointed Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments – J.P. Bushe-Fox – began excavating the Roman site at Richborough.

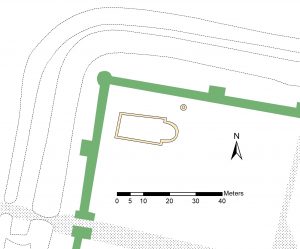

Figure 1: Richborough Roman Fort

The site had been investigated several times over the preceding two hundred years, but Bushe-Fox’s project was the first large-scale excavation of the site to discover what lay between the walls. Bushe-Fox was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (FSA) and had carried out several excavations, first starting at Corbridge, followed by Swarling, Hengistbury Head and Wroxeter, making him a suitable candidate to carry out this work.

The Richborough site itself was included within the chain of Saxon Shore forts listed in the Notitia Dignitatum, a 5th-century manuscript about the organisation of the Roman Empire. This document focused on the massive walls that stood above ground but little else was known. Following Bushe-Fox’s work, a site that spanned several centuries from the initial invasion in AD 43 to the very end of the Roman occupation in the early 5th century was discovered. His results were published in five volumes between 1926 and 1968. The first three were published between 1926 – 1932, with the final two in 1949 and 1968. The gap in the publications was due to an accident which befell Bushe-Fox at Colchester when a trench collapsed on him. The last volume was completed posthumously by Barry Cunliffe at the same time as he was excavating the shore fort at Portchester.

Much of what we know about Richborough comes from these five reports. Other investigations, however, carried out since 1968 and including geophysics and object studies, have added to the story. Even though a bigger picture is gradually emerging, little work has been done on the original paper archive. Kept in Dover Castle, it comprises of more than 50 large binders as well as many photographs, drawings and correspondence. It contains a wealth of records that go beyond what has been published.

Why is reinvestigation important?

Archaeological methods and practice have come a long way in the past century. Techniques of excavation have improved, far more comparative material is available and scientific analysis is revealing new pieces of evidence which were once unobtainable. Going back to basic handwritten reports, however, can also reveal much of what was once overlooked. Brown (1971) stressed exactly this issue when looking at the Richborough archive.

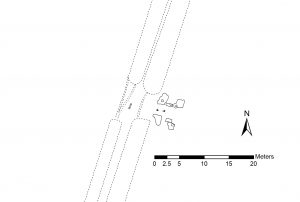

Figure 2: Supposed 4th-5th century church in the NW corner of the fort

Several stone pillars that can be seen on aerial photographs of the time revealed a building that was not clearly seen in the reports. Brown’s reinvestigation led him to interpret the building as a church. Although the interpretation is up for debate, it is clear that delving deep into the archive can add pieces to a very incomplete puzzle. Through my study of the archives, I have found several features that are not investigated in the publications, including an area which might have been used for the barracks.

However, it is not just what was missed that can reveal missing pieces, but also the reinterpretation of old ideas. Hindsight also brings insightful new discoveries or puts under different lights phenomena that were not fully understood at the time. Below are three mysteries of Richborough that have been solved using new techniques and investigation of the archives.

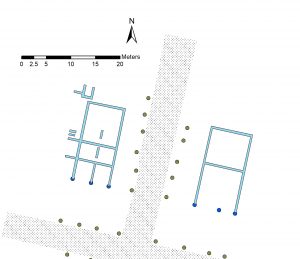

The Claudian Ditch

The two long ditches that form a beachhead on Richborough island have long been considered to be part of the Claudian invasion in AD 43. The ditches were likely part of a camp to secure the landing spot before marching on into Britain. Cunliffe (1968: 232) considered these ditches to have been filled in soon after, probably in AD 44 at the latest. However, at the entrance to this camp were found the foundations of a wooden gateway, which is usually unlikely to be found in such a temporary camp. A reassessment of the coin evidence from the ditch now suggests that these ditches were filled in after AD 50. A copy of a Claudian coin from the ditches was initially dated to AD 41-54. However, the reverse of this coin showed the image of Minerva, which only existed after AD 50. As this is the earliest date the coin could have entered the ditch, the ditches must have been open for between seven to ten years after the invasion. It is therefore far easier to regard Richborough as an earthen rampart fort rather than a camp.

Figure 3: Entrance in the Claudian ditches

The ‘Armoury’

In recent years, much greater consideration has been given to identifying the use of archaeological sites by considering where the objects are found, rather than the perceived use of a building based on its structure. For example, Penelope Allason (2013) studied forts on the Germanic Limes and found that what appeared to be a barrack block, based on its structure, was most likely used for craft activities based on the number of tools found in the building. This approach demonstrated the reuse of buildings in Roman forts. At Richborough, the functions of the buildings are little understood. Some are typical in structure, such as those which have been identified on many sites as granaries. However, it might be more prudent to label these as ‘store buildings’ as their content is unknown. One building on this site in Area 16 was an open fronted timber building. Early in its life, it was made of two separate buildings, parted by a road, but later on the road was removed and the building became one. Its function was unclear until I took a closer look at the findings. Sitting on the floor layer were dozens of pieces of broken armour. Because of their broken state, it appeared as though they were scraps ready to be recycled. Along with these was a pair of iron tongs which would be used by a blacksmith. This evidence points towards this building as the armoury. However, although pieces of armours were found in the building, it is unclear whether the smith only produced armour, or other objects as well. I suspect the latter is the case and that this building should be called a ‘metalsmith’s workshop.’ By identifying this as such, it gives us a better understanding of the activities performed in this excavated area of the fort.

Figure 4: The ‘armoury’ inside the west gate of the later shore fort walls

The East Wall

The location of the east wall is our final mystery from Richborough. In the 1920s, the excavation uncovered what appeared to be an ‘unused’ wall foundation (Bushe-Fox 1932: 22-4). It was presumed to have been unused since the 1790s while researchers believed the wall stood much further out and had been eroded away.

Figure 5: Plan of Richborough with the line of the supposed wall and the line of the actual wall

This assumption was based on a pit cut through the wall foundation which contained coins, none of which could be definitively dated later than AD 273 (Bushe-Fox 1932: 33-4). This suggested that the pit was filled not long afterwards, or at least during the Roman period, and the wall was not originally on this foundation. A look through the coin list for this pit in the archive has now revealed that there was a coin missing from the publication. This coin was dated to AD 390-95. This new evidence shows that the pit must have been dug after AD 395 and demonstrates that the wall could indeed have stood on this foundation. Investigations by Tony Wilmott, built on other evidence, has shown that the wall stood on this foundation but the reconciliation of this pit wraps up the mystery.

Cold Cases Closed

The three cases above show the importance of investigating old archaeological archives. What has been missed by the excavators at the time or wrongly interpreted can lead to decades of assumptions regarding a site. Slowly but surely, a new picture of Richborough is being drawn. Much of what we know about the site comes from the five published reports and these have often been the basis for interpreting the system of shore forts from Norfolk to Sussex; especially since Richborough was the most thoroughly excavated of them. As mentioned previously, hindsight and modern archaeological techniques mean that we are now able to draw on old excavations while finding new stories to tell.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Allison, P. People and Spaces in Roman Military Bases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Brown P. D. C. ‘The Church at Richborough’ Britannia 2 (1971): 225-231.

- Bushe-Fox J.P. Richborough IV. London: Society of Antiquaries, 1932.

- Cunliffe B. W. Richborough V. London: Society of Antiquaries, 1968.