Baiae was a watchword for luxury and pleasure in antiquity, as well as a place to visit for cures in the sulphurous steam that emits from the ground in this volcanic region. Baiae is named after the helmsman in Homer’s Odyssey – Baius (Silus Italicus 8.538-9). Seneca (Letters 51) was very clear about its nature by saying that; ‘luxury has claimed it for her own exclusive resort’ with drunks wandering the beach, riotous sailing parties and lakes ringing with the sound of song and music. The shoreline was seen as a form of a city of villas, from which – according to Seneca – you might count the adulteresses passing in boats. Cicero could list the horrors of Baiae in court as: love, adultery, acting dinners, singing orchestras and boat trips (Pro Caelio 15.35).

The development of bathing in the hot baths fed by what the ancients described as the breath of Giants or for us the thermal springs and other outlets of volcanoes. Livy (41.16) informs us that in 178 BC, the consul Cneius Cornelius visited the Aquae Cumanae in the hope of a cure and this is the earliest indication of the presence of bathing for health in the region. About a century later, we hear that a man named Sergius Orata invented a hanging bath (Pliny Natural History 9.168). Moreover, he brought up villas and added this feature to them, before selling the villa at a considerable profit. Much debate has raged over the precise nature of his invention. Some have suggested that this was the first use of the hypocaust or famous Roman underfloor heating system, others question this and suggest instead that Sergius created jacuzzi like pools with hot water in them. The latter seems more likely meaning for the word balneola, but what is certain is that he made killing by selling real-estate having added a new style of bath building to them.

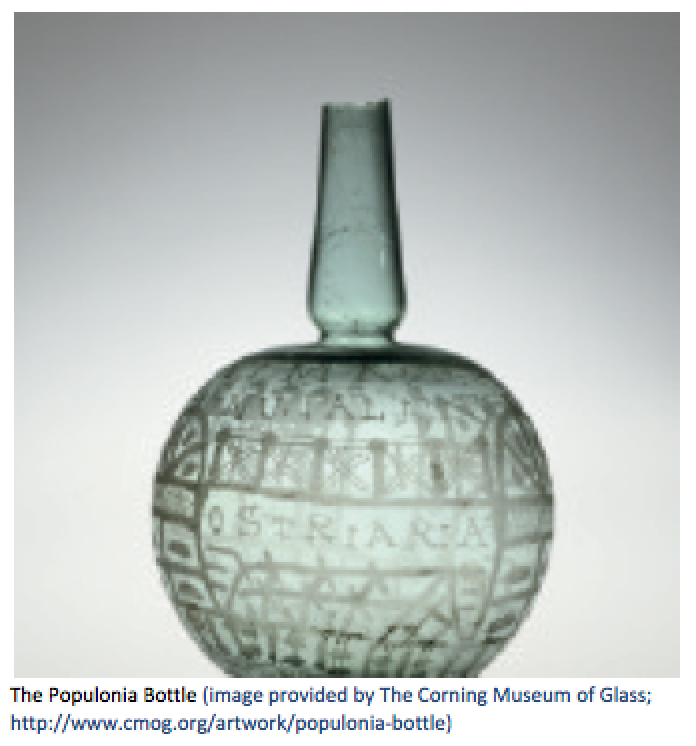

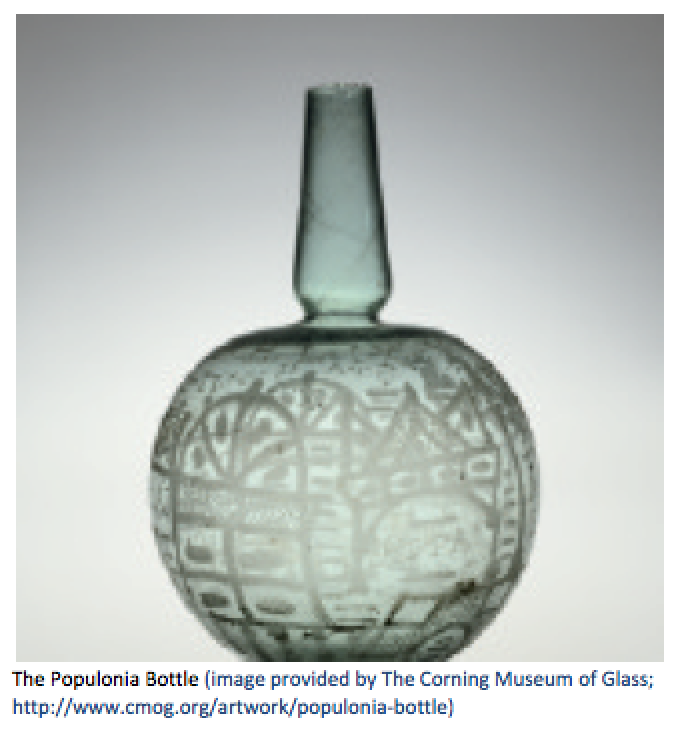

Sergius Orata was also credited with another development at Baiae – the farming of oysters. His surname even reflects the name for a gilt-headed fish. He established the Lucrine lake as the place associated with the very best oysters with the fish pools constructed out into the sea, so that they were washed by the water of the waves, rather than being stagnant pools. The Populonia glass bottle, now on display in The Corning Museum of Glass, shows the landscape of Baiae and clearly shows the oyster beds that lined the Lucrine lake. See if you can identify key features – a lake, a jetty, oyster beds, columns and a palace from the images of below or on the website of The Corning Museum of Glass.

His contemporaries utilised same type of technology to create the first fish ponds for other types of fish. The cost of these pools was considerable of itself, but the fish were also expensive as was their food, as Varro informs his readers of the Res Rusticae (3.17). Many kept fish as pets, rather than for food. Hortensius, Cicero’s oratorical rival, fed his by hand and had fisherman catch fish to feed his own pet fish; whilst if he wanted to eat fish himself – he had it purchased on the quay at Puteoli. At a neighbouring villa, Lucullus had the hill tunnelled to let the sea come into his own fishponds at an enormous cost – at his death, the fish were sold for 3 million sesterces (the annual wage of a legionary was 900 sesterces). Sergius Orata lived to see this new landscape of villas with fishponds develop. Cicero described him as: rich, charming and elegant owning very desirable villas and having charming friends as well as good health. Sergius was seen by others as a brash millionaire who would utilise the law to gain an advantage. His lawyer, L. Licinius Crassus, was a tough customer – but when his pet moray eel died – he went into mourning.

His contemporaries utilised same type of technology to create the first fish ponds for other types of fish. The cost of these pools was considerable of itself, but the fish were also expensive as was their food, as Varro informs his readers of the Res Rusticae (3.17). Many kept fish as pets, rather than for food. Hortensius, Cicero’s oratorical rival, fed his by hand and had fisherman catch fish to feed his own pet fish; whilst if he wanted to eat fish himself – he had it purchased on the quay at Puteoli. At a neighbouring villa, Lucullus had the hill tunnelled to let the sea come into his own fishponds at an enormous cost – at his death, the fish were sold for 3 million sesterces (the annual wage of a legionary was 900 sesterces). Sergius Orata lived to see this new landscape of villas with fishponds develop. Cicero described him as: rich, charming and elegant owning very desirable villas and having charming friends as well as good health. Sergius was seen by others as a brash millionaire who would utilise the law to gain an advantage. His lawyer, L. Licinius Crassus, was a tough customer – but when his pet moray eel died – he went into mourning.

Archaeology, Sculpture and Dinner with a Cyclops

Archaeology, Sculpture and Dinner with a Cyclops

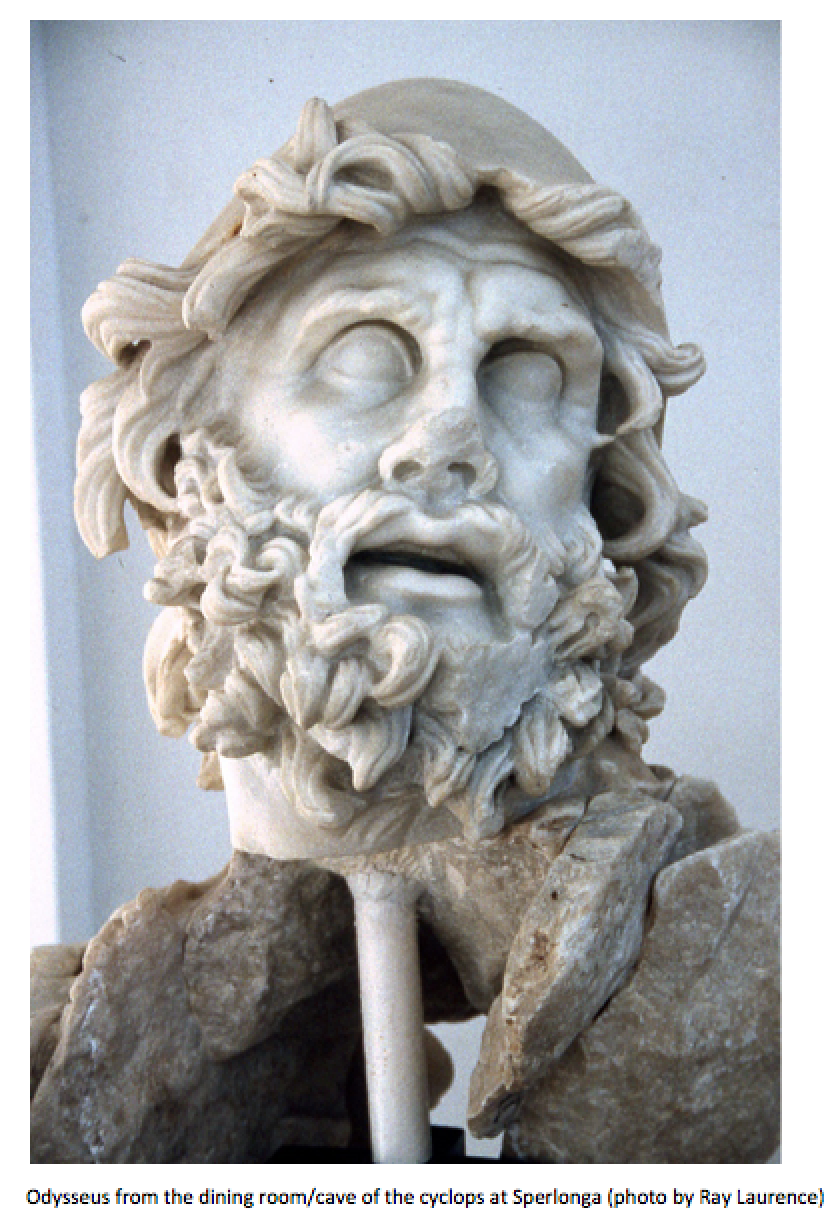

Today, we can see some of the remains of Baiae on the shore but much of the ancient resort lies in the sea within a submerged archaeological park. This is due to changes in sea level associated with plate tectonics – a process known as bradyseism. Beneath the sea they discovered a ‘nymphaeum’ or dining room with a series of statues that included those of Odysseus offering a cup of wine to the cyclops Polyphemus. The story is famous from Homer’s epic poem the Odyssey: the cyclops (a son of Neptune) had just eaten two of Odysseus’ companions and was offered wine to wash down his meal – he had two more cups before falling asleep, a slumber that in Homer’s version included the rather repulsive vomiting of wine, blood and part of humans – prior to Odysseus and his companions blinding the cyclops with a heated up olive branch.

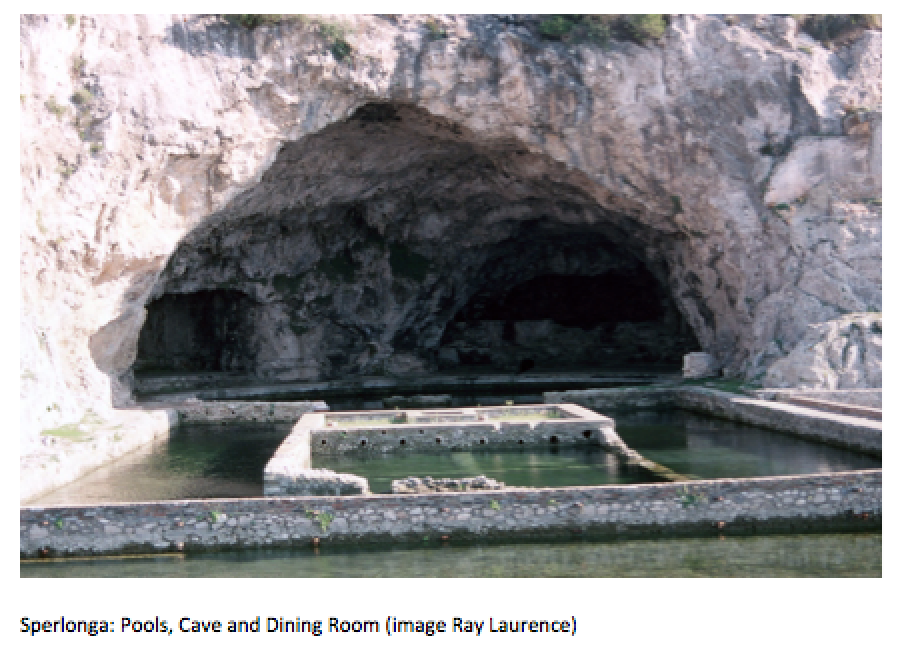

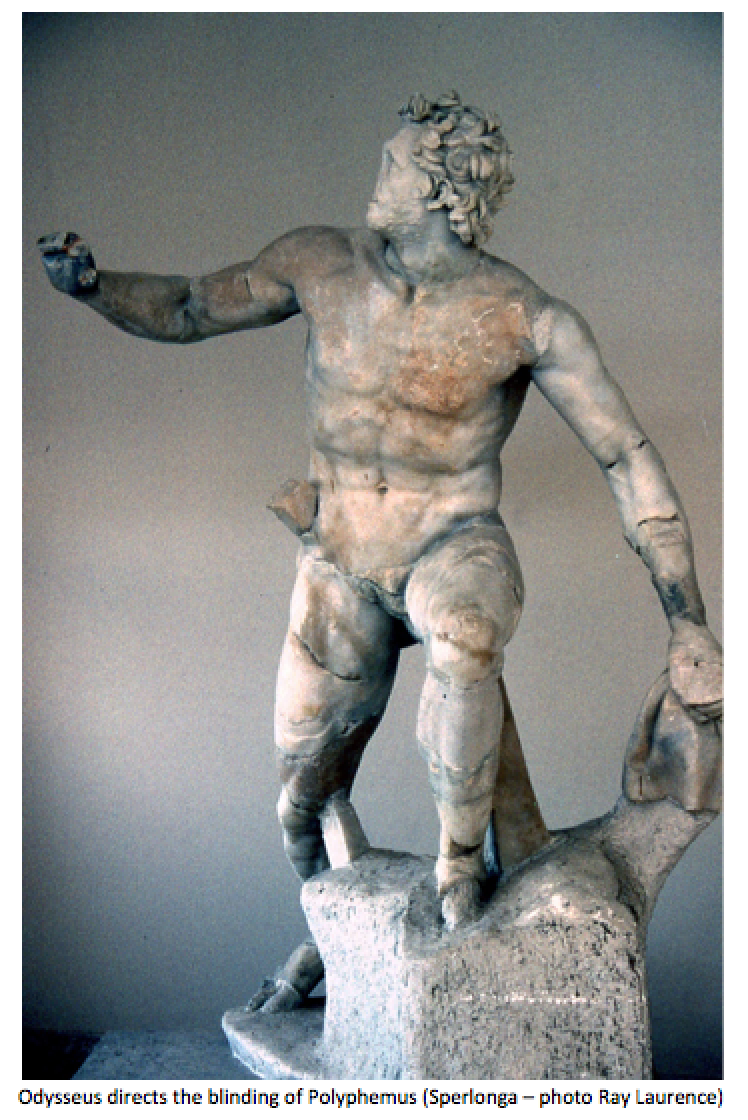

This seems a rather strange adornment to a dining room, but elsewhere in Italy at Sperlonga in a cave that was also a dining room – we also find a massive sculpture of Polyphemus, this time with Odysseus and his companions in the act of blinding him. Other examples in dining rooms, can be found at the Canopus of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli and on Domitian’s property at Ephesus. Nero’s Golden House in Rome was said in antiquity to have had a cave of the Cyclops. Dining in front of the humans being digested by Polyphemus juxtaposed cannibalism with a refined meal.

This seems a rather strange adornment to a dining room, but elsewhere in Italy at Sperlonga in a cave that was also a dining room – we also find a massive sculpture of Polyphemus, this time with Odysseus and his companions in the act of blinding him. Other examples in dining rooms, can be found at the Canopus of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli and on Domitian’s property at Ephesus. Nero’s Golden House in Rome was said in antiquity to have had a cave of the Cyclops. Dining in front of the humans being digested by Polyphemus juxtaposed cannibalism with a refined meal.

Not far from Baiae was the villa of Vedius Pollio at Pausilypo. The villa was inherited by the emperor Augustus, but came with a story of utter revulsion and an example of how not to treat slaves. Seneca sets out the whole issue in De Clementia (18), a work addressed to the emperor Nero. Vedius was hated for fattening his moray eels on the blood of humans. Seneca suggested that there was two possible ways to explain this man’s behaviour: the slaves were food for the fish that he would later eat, or he kept eels so that he might enjoy the spectacle of seeing them eaten. There is a story that when Augustus was dining with him, a slave dropped a precious dish that broke. Vedius fully intended to throw the slave to his eels, but slave pleading with Augustus was saved. The emperor got-up and smashed all the similar dishes to quell Vedius’ anger (Seneca De Ira 3.40.2-5). Later, Vedius’ will stipulated that Augustus should inherit both his house in Rome and this villa on condition that a monumental tomb was created for Vedius. In Rome, the house was demolished and the Porticus of Livia was constructed, no tomb was built and the emperors continued to use the villa on the Bay of Naples. Some sixty years later, Vedius’ fish were still alive and the death of one of them was reported to the senate by Seneca (Pliny Natural History 9.167).

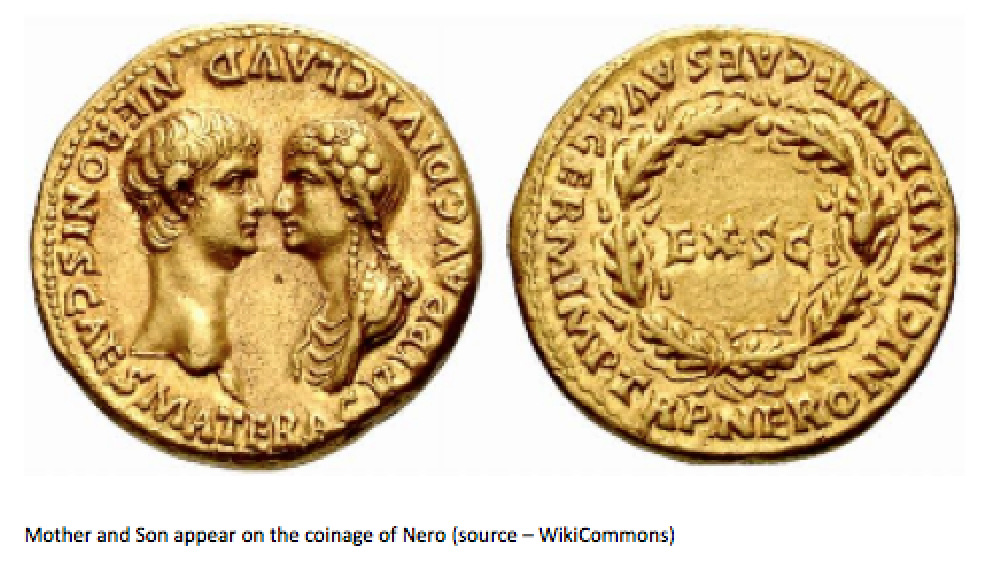

Nero’s Villas and the Murder of His Mother – A Landscape of Power

The remains of the villa at Pausilypo have been investigated and recorded from the early nineteenth century until today. The structures found are similar later imperial villa that of Hadrian at Tivoli. There was a theatre for some 2,000 guests, an odeon for performances on the lyre, singing, and competitions in rhetoric. There were bath buildings similar to those at Baiae, as well as a nymphaeum. This villa formed part of an imperial landscape of villas owned by the emperors. The entire property was run by a procurator – the grave stone of M. Ulpius Euphrates, who lived in the second century AD has been found in Rome records his role in managing the villa (CIL 6.8584). Nero would not only have had access to this villa, but also to Julius Caesar’s villa, although inherited by Augustus, retained the name of his father and was a major landmark high on the hills. He also gained the villa of Piso (Tac.Ann.15.52) and constructed a huge covered lake – the Stagnum Neronis – stretching from Misenum to Lake Avernus. His security was assured by some 10,000 members of the fleet stationed at Misenum commanded by his former tutor Anicetus. He knocked down the villa of his aunt and built a gymnasium for the training of young men (Dio 61.17; Tacitus Annals 13.21.6). It would seem in this landscape that Nero was creating an environment that could produce his adoring fans in the theatre, places for performance, and places of repose for his young followers.

His mother also had a villa nearby close to road from Misenum to the Villa of Julius Caesar at Bauli and it is in this landscape that the drama of his mother murder is laid out for us by Tacitus (Annals 14.4.7). She arrived from Rome by boat and was met by Nero at the shore, from whence they went to her villa. That evening, she was carried in a litter to Baiae and dinner with the emperor. Afterwards, she left by ship rowed by sailors from the fleet. Out at sea, a canopy collapsed in an attempt to kill her but she survived, and the sailors attempted to capsize the vessel. Agrippina swam from the shipwreck to the Lucrine Lake, where she was picked up by bargemen or inshore fishermen and made her way back to her villa. Nero, on hearing of the news, took advice from Seneca and Burrus (the commander of the Praetorian Guard) with the result that sailors under the command of Anicetus were sent to Agrippina’s villa to murder her. Her death was presented to the public as justifiable and the day of her birth was marked as one of ill-omen, like that of Augustus’ enemy Anthony. Prayers and sacrifices of thanks for the emperor’s safety were provided by Nero’s friends at Baiae and by those in the neighbouring towns of Campania. The imperial properties along this shore included a Praetorium (or imperial headquarters) from which Nero’s father had issued edicts to enfranchise the Alpine Tribes, ignoring the senate in Rome, and timing the edict to the Ides of March – the very day of the killing of Julius Caesar. Power rested in this landscape in ways quite different to that found in Rome within the Forum of Augustus, but we need to remember that power was not always public – the emperors had not only monopolised the power of images in the capital, they had also monopolised the properties at Baiae. Nero took things one step further to include within the remit of an emperor training of his voice and his musical ability – existing alongside a gymnasium of youths. It was, here, that the new culture of song and dance that characterised the late first century was created. Later, it would be revealed to the public in theatres and in the circus with Nero performing for them and an audience led in applause by 5000 young men trained at his gymnasium on the Bay of Naples, who saw him as their Apollo whilst he performed a solo role in Orestes the Matricide – a justification for killing his own mother.

Further Reading

Bannon, C. 2014. C. Sergius Orata and the Rhetoric of Fishponds, Classical Quarterly 64: 166-82.

Champlin, E. 2003. Nero (Belnap Press).

Fagan, G.G. 1996. Sergius Orata: Inventor of the Hypocaust?, Phoenix 50: 56-66.

Keppie, L. 2011. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. The Murder of Nero’s Mother in its Topographical Setting, Greece and Rome 58: 33-47.

Laurence, R. 2009. Roman Passions. A History of Pleasure in Imperial Rome, (Continuum)

Squire, M. 2003. Giant Questions: Dining with Polyphemus at Sperlonga and Baiae, Apollo Magazine 158: 29-37.

Wikander, O. 1996. Senators and Equites VI: Caius Sergius Orata and the Invention of the Hypocaust, Opuscula Romana 20: 177-84.