Rachel Arkell is a socio-legal PhD candidate at KLS, working part time as a Research and Projects Officer at the Centre for Reproductive Research and Communication (CRRC) at BPAS. Her supervisor is Professor Ellie Lee – Director of the University of Kent’s Centre for Parenting Culture Studies (CPCS).

Rachel has flourished during her time at Kent. Her co-authored paper Beyond ‘the choice to drink’ in a UK guideline on FASD: the precautionary principle, pregnancy surveillance, and the managed woman was published in a peer-reviewed academic journal at the end of last year, and most recently, as lead author (co-author Prof Ellie Lee), had her article Using meconium to establish prenatal alcohol exposure in the UK: ethical, legal and social considerations published in the BMJ Journals. A subsequent blog comment, by Rachel and Ellie, can be read on the BMJ website.

In this Q&A we find out about Rachel’s research and gain insight into why it’s not ethically or legally justified to use meconium to screen for prenatal alcohol exposure.

What inspired you to carry out research in the field of medication and pregnancy?

I have had a strong interest in the regulation of reproductive autonomy since completing my undergraduate degree at Kent Law School in 2014. I really got to explore this interest during my LLM in medical law and ethics, writing specifically on the criminal prosecution of women who take illegal substances during pregnancy. After my LLM I began working for the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS – the collaborative partner for my PhD project) – and I had begun discussing my proposed PhD with my work colleagues and supervisors (Professors Sally Sheldon and Ellie Lee). In thinking about how to extend my work on the regulation of reproductive autonomy, the idea that women could be withheld access to (potentially) lifesaving medication based on their capacity for pregnancy really stood out to me. It is an area rife with ethical and legal implications, which is vastly under researched.

What led you to specifically carry out research on policy proposals into the use of meconium screening as a tool to establish prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE)?

As part of my role at BPAS, I began researching policy related to the regulation of alcohol use during pregnancy. In 2019 we had seen the start of a new policy framework which sought to screen all pregnant women for their alcohol use throughout pregnancy. Consequently, BPAS registered as a stakeholder for the consultation process for the National Institute of Health and Care Excellent’s (NICE) Quality Standard for Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Embedded within this policy framework were calls for further research into the use of meconium – an infant’s first faeces – as an objective measure of alcohol use during pregnancy. These proposals were made without any ethical or legal justification and would mark an extreme extension of current practice. Both my co-author, Professor Ellie Lee, and myself saw it as an opportunity to examine this omission, adding a critical voice to the policy debate.

Why do you believe it is controversial to monitor PAE markers in meconium?

I believe the controversy lies in the positioning of meconium screening as a ‘reliable’ objective measure of prenatal alcohol exposure. As it could be used to bypass self-reporting by pregnant women, the push to establish the use of technology in this situation further embeds institutional mistrust in what patients report to their healthcare professionals. What is even more shocking about these proposals, is the lack of ethical or legal engagement policymakers have been making. The same criticism was put forward when proposals were made to monitor smoking status in pregnancy through the use of carbon-monoxide (CO) screening within antenatal care. Despite such criticisms, the proposals were successful, and this has now become part of routine antenatal care. It is our hope that by raising these controversies, more care is taken by policymakers to consider what using biomarkers to establish PAE would mean for the relationships of trust between women and their midwives, as opposed to solely focusing on how meconium can be utilised in this setting.

What support did you receive whilst researching for this paper?

I received a huge amount of support from both of my supervisors in the initial stages of planning this paper. Both Professor Sheldon and Professor Lee helped me to formulate the best structure for the paper, which both strengthened my arguments and improved readability. Professor Lee further supported me by joining as co-author and generously shared her expertise and experience in getting the paper ready for publication. I was also supported by my colleagues both within Kent Law School (a special thanks to Natalie Richardson) and beyond, for their reading of early drafts and helpful feedback.

What did you draw upon to reach your conclusion?

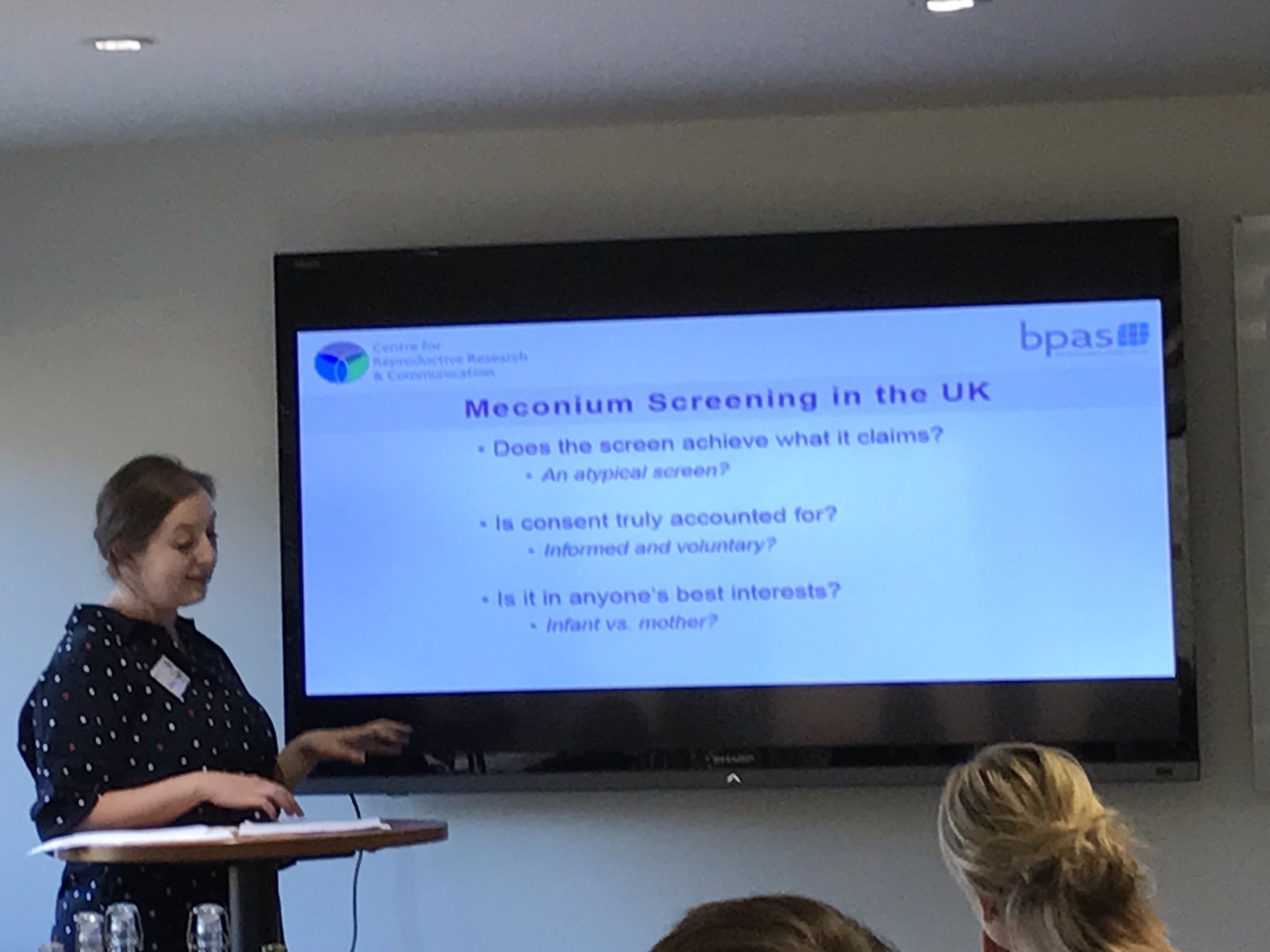

To reach our conclusion that the use of meconium screening (in this case) could not be ethically or legally justified we posited 3 main arguments. First, that the aims of how the screen would be used were not sufficiently clear, and risks further conflating incidences of PAE with a diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Second, we argued that consent has not been adequately accounted for, making reference to the existing compatibility issues surrounding the ‘routinisation’ of other antenatal screening practices and consent. Finally, we argued that the screen could not be deemed to be in anyone’s best interests, emphasising the potential adverse impact on the development of trusting relationships between women and their healthcare practitioners. To make these arguments, we drew on the existing UK policy context the proposals have been made in, and a body of literature speaking to the noted concerns around meconium screening.

Were there any interesting outcomes unrelated the to the topic, but worth noting, during your research?

The most interesting question that came out of my research into meconium screening concerns ownership of information and privacy interests. This question was raised by Dr Pamela White in early conversations I had with her about this paper. We found ourselves questioning “who owns the information related to prenatal exposure” and does the method of collecting this information impact ownership. While this line of enquiry fell outside the remit of the paper, it is an important question which deserves attention.

What’s next for you in your studies in KLS?

I look forward to continuing with my PhD project at KLS and figuring out my next steps.