The History of an Humble Friend [Written by Herself]

A common goal of our research project as a whole is exploring the many questions that the Lady’s Magazine raises about conventional literary historical narratives that have traditionally excluded periodical publications. Part of this exclusion lies in the reputation of many eighteenth-century periodicals as printing derivative content, particularly in terms of the fictional contributions. Robert D. Mayo notes in his book The English Novel in the Magazines, 1740-1815 (1962) that ‘most new magazine fiction published between 1740 and 1815 was lacking in vigor and permanent value’ (2), arguing that such fiction is only worthy of study in its ability to help provide a more complete picture of the eighteenth-century reader. In spite of being frequently considered worthless in its own right, condemned as the products of ‘hacks’ and ‘amateurs’ (Mayo, 2), prose fiction published in the periodicals deserves our close attention.

Examining the fictional content of the Lady’s Magazine in its own right reveals fascinating lines of potential influence from earlier texts and opens up new intertextual possibilities for our readings of later and better known works. Stories such as the anonymously authored The History of an Humble Friend, a serial fiction that appears monthly in the Lady’s Magazine for over two years, beginning in September 1774 and concluding in the yearly supplement to 1776, shares marked similarities to works like Frances Burney’s Evelina (1778) and Ann Radcliffe’s The Italian (1797) – both of which are published years after this humble tale makes its first appearance. This novel length serial fiction deploys standard eighteenth-century Gothic tropes such as the reclamation of the missing mother figure, but does so relatively early on in traditional chronologies of the genre. Likewise, its presentation of the sentimental orphan prefigures later representations popularized in novels by Burney and Charlotte Smith.

Examining the fictional content of the Lady’s Magazine in its own right reveals fascinating lines of potential influence from earlier texts and opens up new intertextual possibilities for our readings of later and better known works. Stories such as the anonymously authored The History of an Humble Friend, a serial fiction that appears monthly in the Lady’s Magazine for over two years, beginning in September 1774 and concluding in the yearly supplement to 1776, shares marked similarities to works like Frances Burney’s Evelina (1778) and Ann Radcliffe’s The Italian (1797) – both of which are published years after this humble tale makes its first appearance. This novel length serial fiction deploys standard eighteenth-century Gothic tropes such as the reclamation of the missing mother figure, but does so relatively early on in traditional chronologies of the genre. Likewise, its presentation of the sentimental orphan prefigures later representations popularized in novels by Burney and Charlotte Smith.

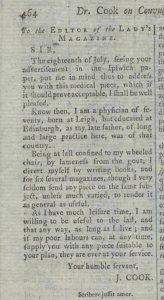

LM, V (1774). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The story provides a first-person account by the narrator, Harriot West, an orphan whom we first encounter in the boarding school outside of London where she was raised by the kindly Mrs. S—. When Harriot visits a schoolmate during the holidays she is sharply reminded of her forlorn position in the world by her hostess who, in an effort to curtail her husband’s teasing, tells him that Harriet is ‘only a poor child, whom nobody owned, and for whom, of course, nobody cared’ (V, 577). Harriot realizes that her lack of family means that she can ‘expect mortifying treatment’ and she reflects ‘I felt myself detached, as it were, from every human creature, I felt myself a solitary being, in the wide world, without a parent, without a friend, without a protector’ (V, 578). Following a familiar pattern in eighteenth-century literature, Harriot’s orphaned state is compounded by having no knowledge of her birth parents, and though her adventures eventually lead her on a journey of discovery: of family, fortune and love, she must first endure hardship and dangers.

LM, V (1774). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Part of the story’s appeal is the writing itself: the anonymous author is engaging and amusing, quickly drawing readers into Harriot’s narrative. Following her into ‘the world’ reveals, much like Frances Burney’s eponymous heroine Evelina (1778) experienced, how perilous navigating society without name or fortune could be. Harriot’s treatment at the hands of other young women confirms her initial fears that she can expect mortifying treatment. Positioned as her schoolmate’s companion she accompanies the Ludlow family on visits, to the opera, and to plays. Threatened by her beauty, Miss Ludlow’s friends attempt to persuade her that Harriot, ‘though she had nothing, and was nobody, yet made a specious appearance, which attracted the eyes of the men, and drew them from women infinitely superior to her in every respect; women who had both fortune and birth to recommend them’ (V, 645). Indeed, when the visit eventually concludes, Harriot is determined to become a teacher at the boarding school so she will not be exposed to such treatment in future.

Fortunately for the story’s readers, the author has no intention of keeping Harriot ensconced safely in Mrs. S—’s school. Believing that Harriot will be better served by making alliances with good families, Mrs. S— encourages her to visit another young lady from the school, Miss Menel, who is handsome, rich and vain. Miss Menel comes equipped with both a handsome brother, Mr. Menel, and a lover irritated by her caprice, Mr. Lovell. Harriot finds herself the object of unwanted attention from Mr. Lovell and both Miss Menel and her brother ‘became alarmed at his behaviour’ (V, 691).

It is here, questioned closely by Mr. Menel over her feelings towards his sister’s lover, that we will leave Harriot feeling ‘hurt and abashed’ (V, 691). In future posts I will pick up on the serial’s weaving together of various generic conventions; much like Harriot’s narrative, this thread will be continued periodically.

LM, V (1774). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.