The frantic barking of the dog at the sound of the doorbell today didn’t result in the usual volley of curses but saw me leaping out of bed shouting “It’s the mailman! It’s the mailman!”

“Postman!” corrected my partner, grumbling irritably and pulling the duvet over his head.

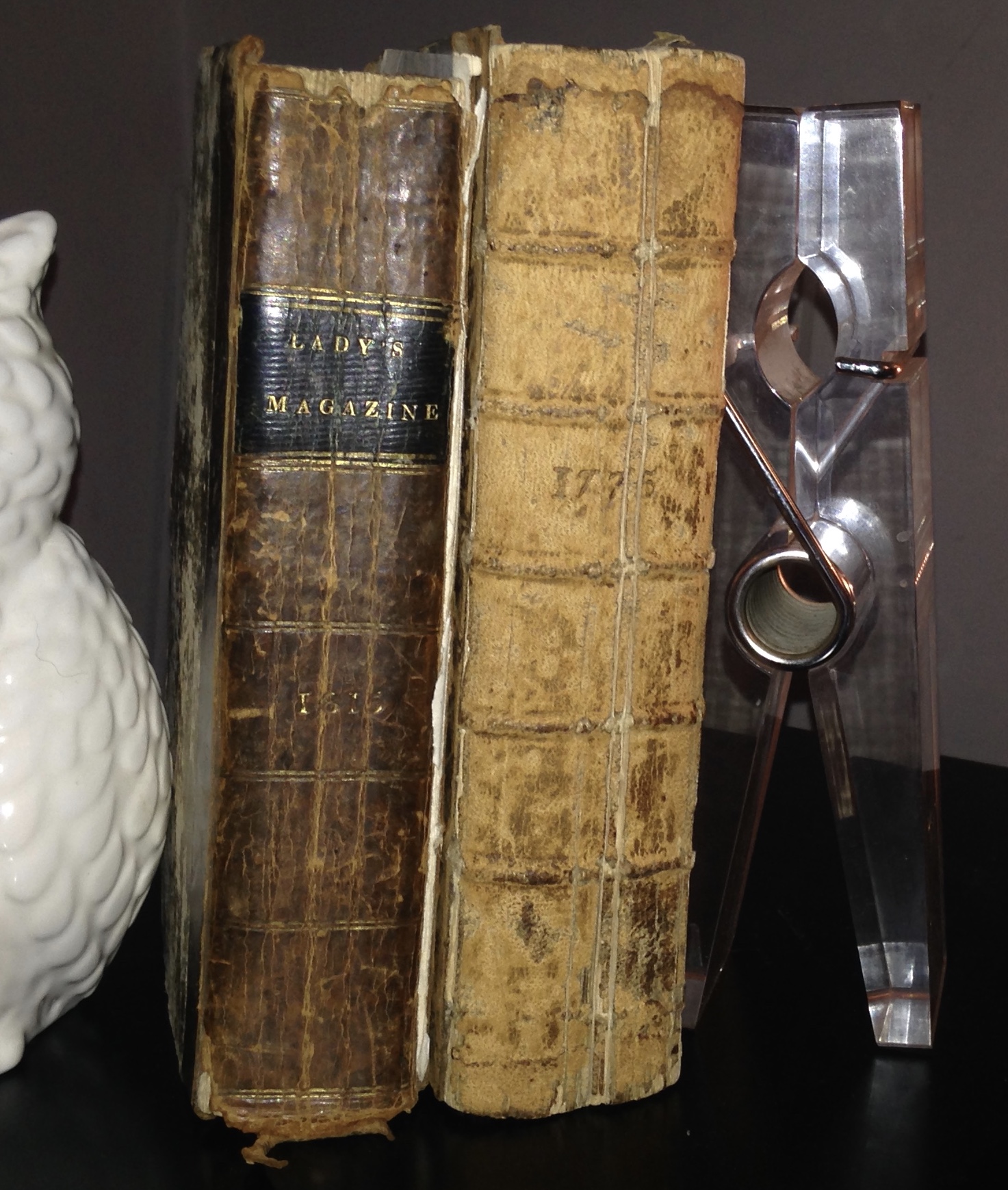

My unusual excitement at being woken by man and beast was because of the anticipated delivery: a volume of the 1815 Lady’s Magazine. Ever since I bought a 1775 edition of the magazine I’ve been looking for another good deal (which for me means damaged but with as many engravings/plates/patterns as possible) and when 1815 appeared for sale with four fashion plates the opportunity was too good to miss.

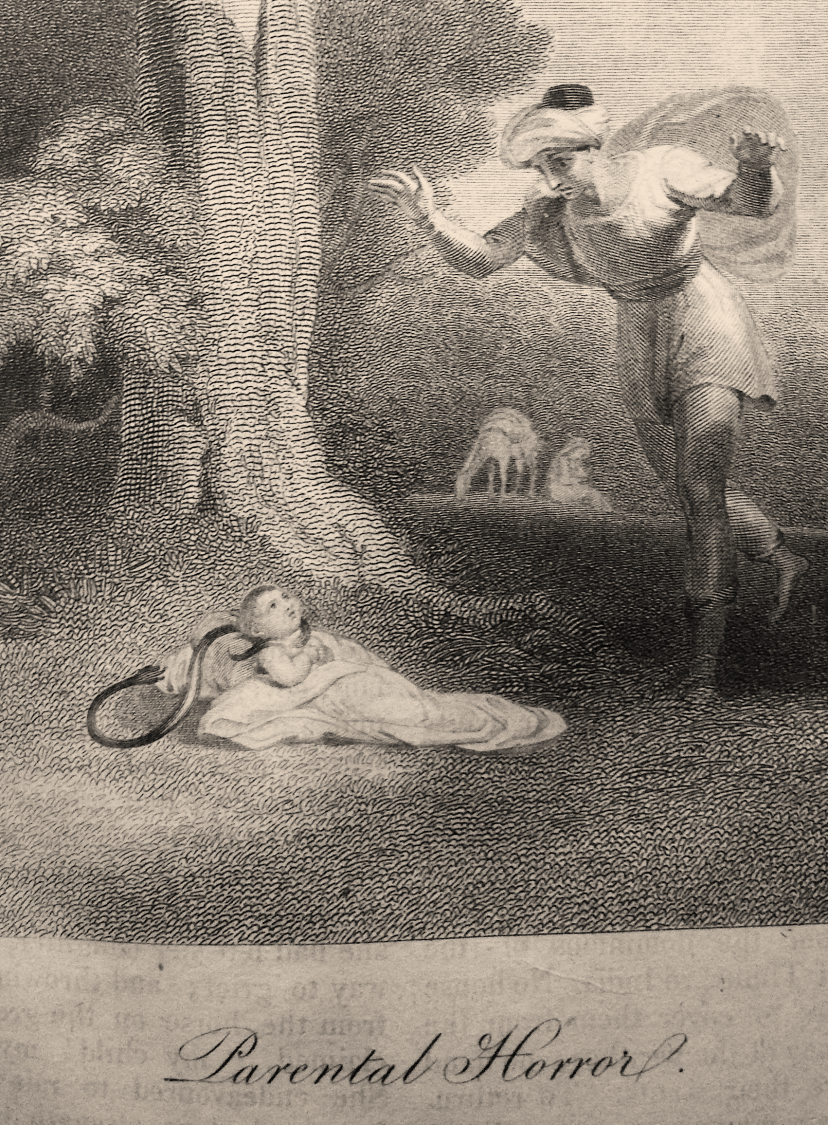

For today’s post I leave off my ‘researcher’ hat and simply share my excitement at my new (old) edition of 1815 and some pictures of the engravings and plates that I’ve edited a bit to show off the really extraordinary skill of the artists. Although the engravings are one of the aspects of the magazine that we know little about (for most of the first series of the periodical they have no artist signatures or printer’s details) they have clearly been carefully chosen by the editors to accompany the tales and, at times, they are commissioned specifically for the stories.

One of the reasons the physical copies of the magazine are of such interest to researchers (and especially those who most frequently read the magazine in its digitized form) is of course the possibility of coming across something that is missing from the digitized edition. For example, the digitized edition of 1818 lacks several pages, so if you have only been able to access that edition the presence of those missing pages is welcome. Another reason to love the physical magazine is the possibility (that faint hope of treasure that keeps people like myself metal-detecting for hours in the rain) of finding something missing not only from the digitized edition, but likewise missing from most other volumes – such as a pattern unseen for over a hundred years, or an advertisement removed by the binders. And searching for such a possibility, I discovered something rather odd.

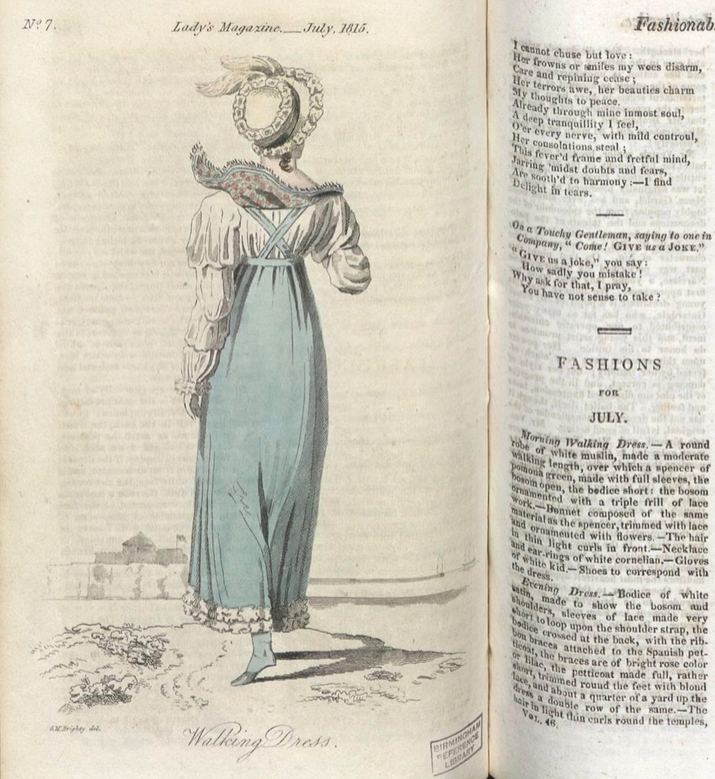

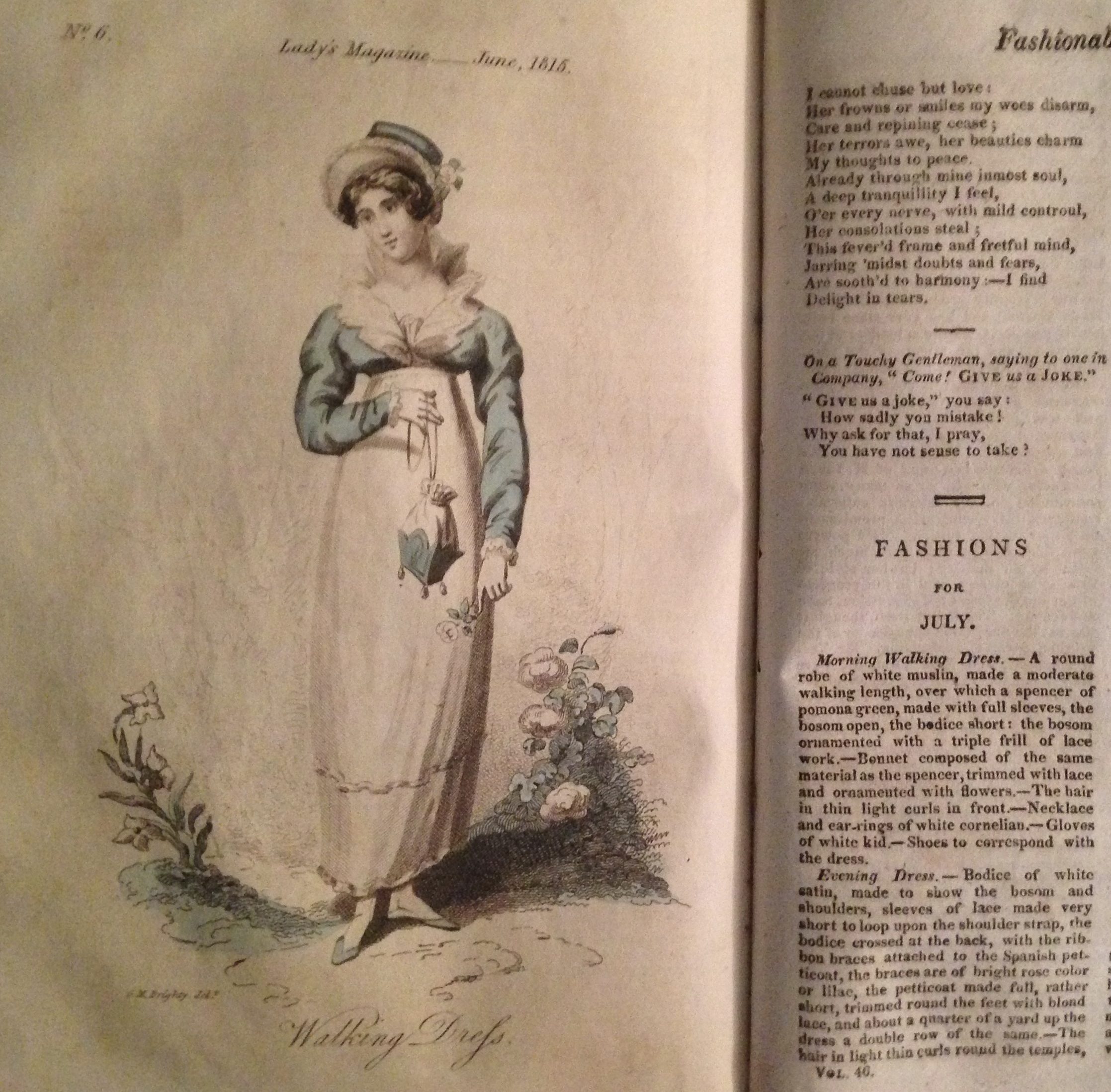

My volume of 1815 does indeed appear to have a fashion plate missing from the digital edition — it is opposite page 285 in my edition and is an engraving of a walking dress described in ‘Fashions for July’. The digitised edition also has an engraving for July depicting a walking dress, but it’s a different engraving. My engraving is numbered 6 in the upper left corner, while the digitised copy’s engraving is numbered 7. Curious indeed! Apparently my binder inserted the June engraving into July while the digitised edition is missing June’s entirely.

But even when these exciting possibilities fail to materialise, the material of the magazine is fascinating enough in its own right. I’ve written before about the differences between working with physical and digital editions: I love the ease of the digitized magazine for work, for speed, for accessibility, for being able to drink a cup of coffee without fear of destroying something priceless, and so on. Yet the beauty of the fashion plates and engravings is undeniably enhanced by seeing them close up in person when the detail of the engravings, the strokes of the etchings, the brightness of the colours appear as if they were printed yesterday, not 200 years ago.

1815 was an especially rich year for engravings; it includes several portraits of famous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century personages, including Byron, Lucien Bonaparte, Lord Castlereagh, Amelia Opie and others. The illustrations to the fictional content are likewise particularly intriguing; ‘Parental Horror’ depicts a father witness a snake coil around his infant’s neck while ‘The Charm of Modesty’ shows the youth Lycophron discern his lover Aglaia from a group of women enchanted to appear identical to her only by virtue of her downcast, modest eye.

The engravings present an opportunity to learn more about the printing process and editorial decisions behind the scenes of the finished product, yet at the moment they remain frustratingly silent. Where did they appear first, who selected them for use in the magazine, who printed them and who wrote the stories for which they were commissioned? Hopefully as we proceed with our work on the project and uncover more about the mysterious editors and publishers behind the magazine we will learn more about the illustrations and plates that were a constant feature and important selling point throughout the over 62 year print run of the Lady’s Magazine.

But for now, enjoy the pictures.

Dr Jenny DiPlacidi

University of Kent

I love the Regency era. Don’t know what it is that attracts me to it, but I can agree with you about the magazines. Would love to actually hold one. You mentioned how the engravings look like they were done yesterday. Pastel paintings are like that as well. Oils darken with age and watercolors fade, but pastels are like the engravings. I also found it interesting that Amelia Opie lived to age 84. So many times we hear how short-lived people were back then. Lack of hygiene, weak genes and other factors probably entered in. But there were quite a few who lived to a ripe old age. Thomas Lefroy was 93 when he died, so it was possible even back then.

Thanks, Sharon, for giving us a little closer look at that era.

Lucien Bonaparte looks like 1995’s Charles Bingley. Remarkable.