In my previous post on the material aspects of the Lady’s Magazine (1770-1832), I briefly touched upon the advertisements that were printed on the wrappers of the magazine’s monthly issues, with the promise to return to them later. As I said there, periodicals like the Lady’s Magazine have predominantly been handed down to us in the form of bound annual volumes, which has led to the irrecoverable loss of a lot of information. The binders apparently felt that, in order to transform these periodicals into historical documents with a lasting relevance, they needed to purge the numbers of elements that they judged to be too ephemeral, because these would tie them to their original moment of appearance. We have said before that we are already very grateful for the one complete issue that is kept in the University of Kent’s Templeman Library, so you can imagine our excitement when our project PI Jennie Batchelor discovered a whole host of copies in the fantastic Special Collections and Archives library (SCOLAR) at Cardiff University that, though still missing other bits, had retained a lot of their adverts. All three researchers on our project will need to go back to Cardiff to take a closer look at these items, and I will be particularly interested in the advertisements they contain. In this post I look in some detail at the adverts in the October 1771 issue held at Kent, and then briefly glance ahead at what the Cardiff collection holds in store.

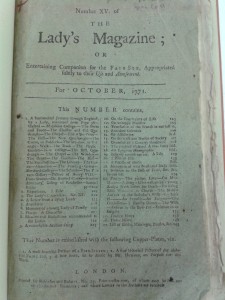

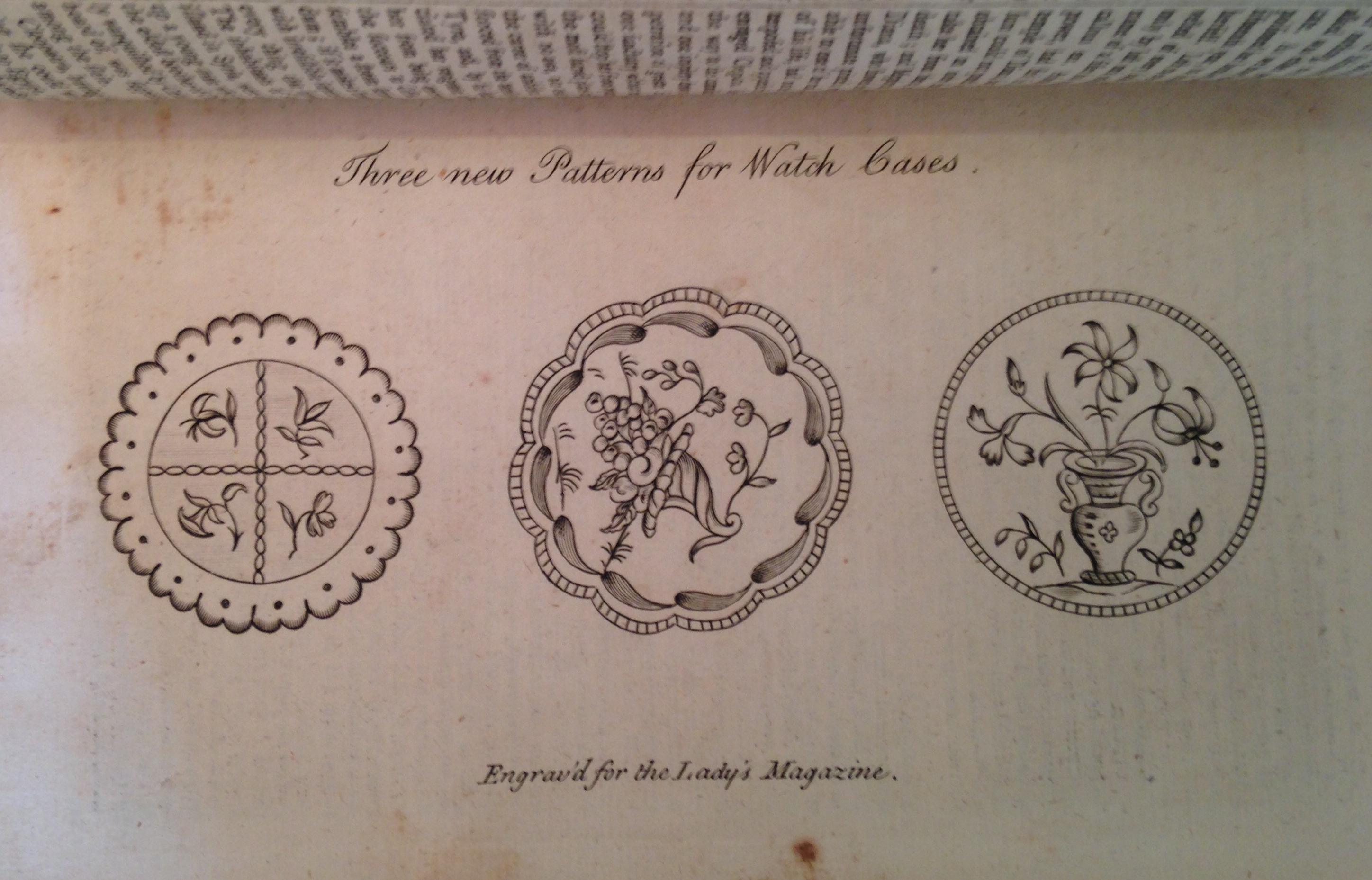

In October 1771, and likely throughout the first two or three decades of the magazine, the adverts are situated on the wrappers, or paper covers that guarded the magazine proper for every monthly issue. These wrappers do not offer much in the way of protection of the main body of the periodical, because they are only made of a slightly coarser paper than is used for the pages of the magazine. This is nothing out of the ordinary for periodicals of this period, like the Lady’s Magazine, of which the publishers wanted to keep the production costs down so that a lower price could be charged that kept the magazine within reach of a wide audience. In fact, this is one way in which looking at the used materials, as described in my previous post, can tell you much about the market positioning of the periodical in question. The primary function of these wrappers is therefore not to guard the magazine proper, but to offer a liminal zone; a threshold between reader and text, for those features of the magazine that were considered more ephemeral than even the periodical text itself. Publishers knew that most readers did not hold on to these wrappers anyway, and printed the types of notices there that readers were likely to want to remove from their preserved personal library copies. The recto side (i.e. the side facing you when the mag is closed and facing upwards) of the front cover features a masthead, a table of contents (ephemeral too because made redundant by the annual index issued with the thirteenth number), a description of the included plates, and contact details on the publishers. My colleagues and I pay close attention to the listed plates because these include supplemental loose addenda that mentioned nowhere else, originally probably either inserted loosely or ‘tipped in’ ( jargon for glued provisionally into the periodical by the upper left corner), and as a rule missing from the library copies.

This ephemerality argument also applies to the advertisements. Newspapers at the time had often extensive advertisement sections in the form of the ‘classifieds’ that you still get in some papers today, but most magazines, encouraging the perception of their collected annual volumes as actual books with a lasting value, would keep their adverts contained in neatly demarcated and therefore easily removable sections. In the October 1771 issue, the Lady’s Magazine’s adverts appear on the verso side of the front cover, and on both recto and verso of the back. Like the price of the periodical and the materials that went into its production, the type of services and goods that are advertised here also tell us a lot about the audience that the magazine sought to address at the time. Then as now, advertisers of course did not want to waste their money by buying space in publications that were not read by their target demographic. Of the five adverts that appear with this number, four are for other publications. The first is for the successful encyclopaedic reference work A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar, published by J[ohn] Knox. It may seem odd that the Lady’s Magazine’s publisher Robinson would tolerate such prominent advertisements for the wares of competitors in his own flagship periodical, but it is possible that Robinson owned a share of the copyright and thereby would benefit directly from the sales as well. As quite often in this period several ‘booksellers’ would pool funds to pay for more ambitious publication ventures together. This book also contains biographical profiles of the kind from which the magazine’s staff writers loved to distil “historical anecdotes”, and the promotion and expansion of this work through consecutive editions, would there be a clever investment.

As is explicitly stated in the page-length advert on the recto side of the back cover, Robinson was definitely one of the publishers for the Royal English Dictionary (1761). Just like the previously advertised work, this publication, originally published hot on the heels of Dr. Johnson’s by esteemed grammarian Daniel Fenning, fits in with the interests of the magazine’s broad readership. It was published in cheap editions as well as more luxurious ones, and offered knowledge with an attempt at impartiality and appropriateness for women, on topics that would be valued by socially aspirational British middleclass families. The verso of the back cover has three smaller adverts, of which two are for very similar periodicals. The first is for the Ladies’ Own Memorandum-book, or, Daily Pocket Journal, published by Robinson, and the second for the Ladies’ Annual Journal, or, Complete Pocket-book, indicated as published ‘for Elizabeth Stevens’; about whom I have not found any information. Please help us out in the comments section if you know anything about this person! Anyway, both titles are annual publications that contain regular women’s periodical fare as offered by the Lady’s Magazine, combined with items on different domestic duties such as keeping household expenses accounts and coach travel that, as the subtitle of the Memorandum-book indicated, then constituted ‘the Transactions of Business’ of middleclass women.

Now, this standard eighteenth-century self-cultivation through knowledge, improvement of one’s vocab to emulate the upper classes, and gaining efficiency in household management is all well and good, but as the Lady’s Magazine occasionally advised, one must not totally neglect the care for the outer person either. The last advertisement is for once not for a book or periodical, but for a cosmetic product. The ‘Bloom of Circassia’ is not a 1985 Woody Allen film, but apparently an ointment that would impart ‘a rosy Hue to the Cheeks, not to be distinguished from the lively and animated Bloom of rural Beauty’. Funnily, even this beauty product is to be purchased from booksellers. These gentlemen kept surprisingly versatile businesses.

As I already announced above, we will dedicate more blog posts to the subject of advertising in the Lady’s Magazine. The copies of early-nineteenth-century issues that Jennie looked at in Cardiff contain more numerous and diverse advertisements, which are not restricted to the wrappers. Extensive advertisement sections appear there, that normally hardly ever make it into the annual volumes because private owners and librarians have long since taken them out. I am looking forward a lot to doing more research on those, and will keep you posted on what I find out!