LM XLIII (December 1812). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Drama appears in the Lady’s Magazine throughout its over sixty year print run in numerous forms. The most frequent genre is the review, but the theatrical world is also presented to the magazine’s readers through, for example, biographical essays on actors and actresses, excerpts from plays, songs from new productions, engravings of theatres and performers and translations of (primarily) German and French dramas.

LM I (December 1770): 227. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

From its commencement in 1770 the magazine demonstrates its engagement with the contemporary theatrical milieu – in December 1770 a contributor who signs himself Theatricus offers an essay including anecdotes about morally jeopardized individuals who repent after seeing plays in which their weakness (such as gaming) are exposed. ‘The Remarkable Effects of Theatrical Representations’ functions as a conduct work, opinion piece, and tract on morality but also blatantly promotes English theatre and ‘the great utility of Theatrical amusements’ (LM I [December 1770]: 227). The piece mentions some of these useful plays – The Provoked Husband and George Barnwell – and concludes with the hope that ‘our nobility would raise the same subscription, and appropriate the same house that they now use for Italian operas, to a good set of English actors’ (LM I [December 1770]: 227). The first year of the magazine also includes a range of reviews of plays such as Clementina, a tragedy, and the Madman, a burletta. Reviews (or ‘accounts of’ different plays as they are described in the periodical) appear dispersed throughout the other items in each monthly installment, which usually includes 1-4 such reviews.

LM XLIV (Supplement 1813). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

While the reviews remain a standard feature of the periodical, preliminary research indicates that there is a sharp decline in their appearance from 1811-1813. Indeed, during this three year span any mention of theatre is scarce. Exceptions to the paucity of theatrical material include biographical sketches of Sarah Siddons in 1812 and in the 1813 supplement an account of Miss Smith (Sarah Bartley). In 1814 the reviews are consolidated into a single section called ‘Dramatic Intelligence’ which is subdivided into sections by the individual theatre. After this the periodical undergoes another refashioning and from 1818 reviews are located under the section entitled simply ‘Drama’.

In the early years of the magazine the theatrical reviews were primarily synoptic, including details of the performers and either extracts from the play or summaries of the plots, and offering little criticism. For example, the January 1771 reviews of Almida and the West-Indian detail the location, actors and actresses and parts alongside lengthy descriptions of the plays and describe the audience reception. This is a fairly standard formula for the majority of the reviews throughout the lifetime of the magazine, but in the early 1780s some of the reviews do begin to include more critical examinations of the plays’ content. Such more critical reviews run alongside the conventional summary model for the duration of the periodical.

LM XII (June 1781): 321. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

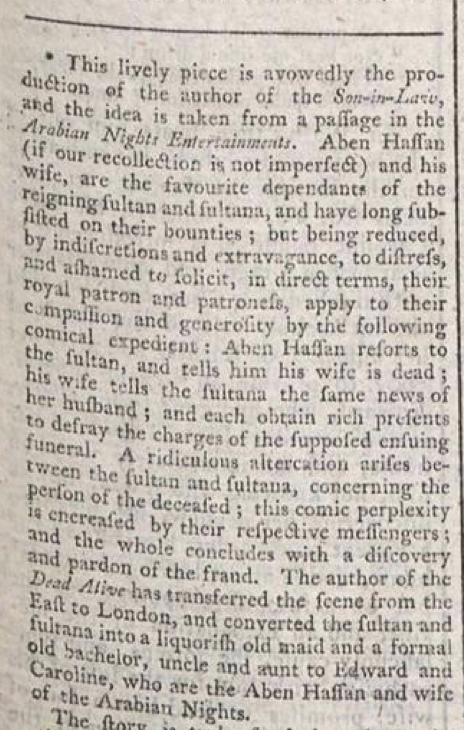

The account of the Dead Alive, a farce, in June 1781, is one of the first that alters the traditional model of reviews. This ‘account’ does so by introducing the critical commentary in the form of a very lengthy footnote. This style is not a common one; although reviews do occasionally appear with commentary provided in the footnotes, more often the reviews embed the criticism within the body of the article. But in the account of the Dead Alive the unsigned writer opens with ‘The piece*’ and then includes her opinion in the subscript marked by the *. The body of the account continues with the traditional summary of the play’s plot. The writer states in the opinion subsection that the play, taken from a passage in the Arabian Nights Entertainment, has been ‘transferred’ by the playwright from ‘the East to London, and converted the sultan and sultana into a liquorish old maid and a formal old bachelor’ (LM XII [June 1781]: 321).

Arguing that the play is ‘avowedly the production of the author of the Son-in-Law’ the contributor notes that the play is ‘enlivened with that peculiar vein of humour, those droll equivoques, and odd turns, that distinguish the author of The Son-in-Law’ (LM XII [June 1781]: 321). The anonymous writer also comments on the originality of the characters, pointing out that the character of Motley, ‘though touched by a more masterly hand in The Apprentice, and more recently displayed in All the World’s a Stage, still derives some originality from the author’s management of it’ (LM XII [June 1781]: 321). Complimenting the performances of the company, the acting ability of particularly Mr. Edwin, who played Motley, is described as excellent. The body of the review, after summarizing the plot, provides some of the songs.

LM XII (May 1781): 316. Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

Another review that makes use of footnotes or subscript for the critical content is the serial feature on the ‘Spendthrift, compared with The Generous Imposter’ from the French of Des Touches. This review is particularly interesting because it is the first I found that offers a sustained and serial critique of the effectiveness of the translation, rather than the play itself. Although not all of the installments include lengthy discourse comparing the translation to the original, there are many that do, and such passages focus particularly on the ability of the author to convey to and/or modify for an English audience the sentiment and humour of the French original.

Other genres, such as the essay, provide biographies of celebrated actors and actresses, often extracted from memoirs or autobiographies. Especially in later years these essays are accompanied by engravings of the individual, such as Sarah Siddons, one of the more celebrated actresses of the eighteenth century. Mrs Siddons’ enduring popularity is demonstrated by her appearance in the magazine in various genres including theatrical reviews, engravings, and as the subject of poetic odes from (at least) the 1780s through the 1820s. Other actresses and playwrights appearing in engravings include Hannah Cowley and Dorothea Jordan.

LM XVI (December 1785). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

The enduring prevalence and shifts in the material concerned with the theatre within the Lady’s Magazine offers fascinating insights and information on both the reception of plays and translations but also the changing sociopolitical contexts in which productions were staged and received. The range of genres that make use of dramatic pieces, language, and influences for a range of purposes reflects the engagement of readers and contributors with the contemporaneous theatrical world. Although this preliminary research raises more questions than it answers at this stage, it provides an important glimpse at the shifts in both the types of genres (essays, reviews, opinion pieces, etc.) that engage with a popular and constant topic within the periodical, and the shifts within a specific genre, such as the review.

Jenny DiPlacidi

University of Kent