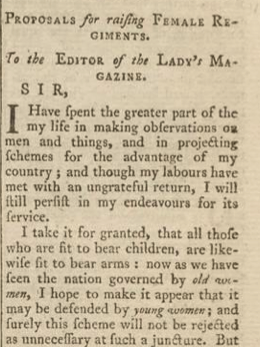

LM, IX (November 1778): 583. © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

While writing my last blog post on the diverse genres of items mentioning or concerned with female fashions I initially included a November 1778 letter to the editor entitled ‘Proposal for Raising Female Regiments.’ The letter was, at first glance, a satirical epistle with multiple targets including French soldiers and domineering wives. However, something about the material didn’t feel quite right; it didn’t read like the average letter to the editor. I began searching for some of the unique terms in the text and it was the phrase advocating women ‘be cloathed in vests of pink sattin, and open drawers of the same’ (LM, IX [Nov 1778]: 584) that led me to the discovery that the letter was not, in fact, an anonymous epistle, but an essay attributed to Oliver Goldsmith.

While the attribution isn’t made until an edited collection of Goldsmith is published in the 1790s, the letter/essay had been appearing in periodicals and gazettes since January 1762. The satirical epistle is signed T.S. in the Lady’s Magazine as, I believe, a nod to Tobias Smollet, the editor of the British Magazine where it first appeared. The essay’s edited form in the Lady’s Magazine removes any details that would reveal the original date of publication, yet leaves the mention of attacking the French troops intact — at the time of its initial publication the reference was propaganda regarding the Seven Years’ War. There are also other explicit references in the original essay that clearly locates it as having been written within 1762 and which have all been removed to make its insertion in the 1778 volume of the Lady’s Magazine topical. Likely, the letter to the editor would have been read as satirizing the French soldiers participating in the American War of Independence.

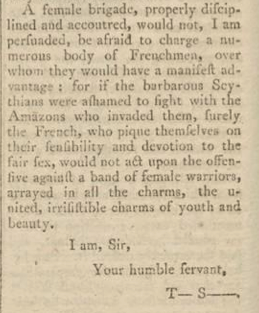

LM, IX (November 1778): 584. © Adam Matthew Digital / British Library. Not to be reproduced without permission

The contributor has repurposed and repackaged the Goldsmith essay so that it becomes newly relevant, appearing as a just-penned letter to the editor. Yet signing the letter ‘T.S.’ indicates that the contributor doesn’t intend to use the text without giving credit to the earliest place of publication (at the time, this was the only information available regarding its source). As my previous blog post reveals, the nuances of the letter’s authorship left me unable to tackle the material within the brevity of the blog. The Goldsmith essay has a whole life outside of the Lady’s Magazine where it is eventually repurposed, but so too does its appearance within the periodical engage with the other items concerned with dress, gender, citizenship, and education.

What this example points to, I believe, is not only the way that the roles of authorship and content research on this project overlap, but also the challenges in writing about the items in the Lady’s Magazine. The complexity involved in uncovering authorship and contextualizing the content highlights the collaboration that is so necessary for the project and that speaks to the dialogic nature of the magazine itself. Part of what is so exciting and interesting about working on the Lady’s Magazine is how much we are constantly learning about eighteenth-century print culture, readers, and authorship.

Dr Jenny DiPlacidi

School of English, University of Kent