LM, V (1774). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

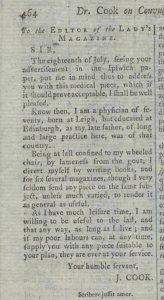

Among the many interesting reader contributions to the Lady’s Magazine are the items that seek or offer advice on medical issues. One of the periodical’s major sources of medical expertise was Dr John Cook, who began corresponding with the magazine in September 1774. Dr Cook, a 70 year-old physician confined to a wheelchair by gout, seeks to be ‘useful to the last’ by sending in medical pieces to a variety of periodicals. Eighteenth-century patients, overwhelmed with recipes for ‘vulgar specificks’ made up of ‘cat’s-blood, powder of the human skull, and many other such mysterial medicines’ of ‘imagined virtues’ (V, 464), could consult the magazine’s long-running column The Lady’s Physician for professional medical guidance.

LM, VIII (1777). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

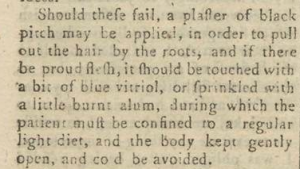

To a modern reader, Dr Cook’s advice can appear to border on the downright dangerous. At one point he suggests that mothers who are having a particularly difficult time curing their infants’ scabbed head use a plaster of black pitch (a tar-like substance) to coat the head and pull the hairs out by the roots (VIII, 41). Nonetheless, the medical advice on offer was seldom without precedent. Running from 1774-1786, with Dr William Turnbull taking over from Dr Cook in November 1783, The Lady’s Physician provided cures believed to be tried and true – though often with modifications. Dr Boerhaave’s recipe for a poultice to apply to breasts infected with coagulated milk, was, for example, offered by Cook along with his own explicit directions, measurements and comforting tone (VI, 256). For those ladies whose breasts are so infected they require suppuration, Cook assures them that they ‘need not be terrified at so slight an operation’ that is not ‘cutting into the solid flesh, as you may fear, but only piercing at once a very thin and overstretched skin … if speedily performed, both the horror and pain will be over before can well be cried oh!’ (VI, 257).

LM, IV (1773). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

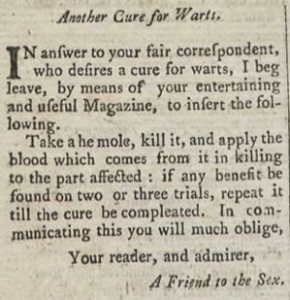

Not all who wrote to the magazine offering advice were as professional as Cook. In response to Sylviana, who requested a cure for the ‘disagreeable’ warts that have ‘over-grown’ her hands (IV, 600), one reader suggested she slaughter a mole and bathe her warts in its blood (IV, 660). For readers like Sylviana, whose warts caused her mortification, the dialogue provided by the magazine’s reader contribution and response format allowed for questions and conversations that would have otherwise gone unasked and unspoken. Serials such as The Lady’s Physicican in some ways functioned as an eighteenth-century Embarrassing Bodies, but without the need for self-exposure. Cook himself expressed a desire that the column would help women with diseases ‘the modesty of many will not permit them to consult a physician about’ (V, 578).

LM, IV (1773). Image © Adam Matthew Digital / Birmingham Central Library. Not to be reproduced without permission.

And as for quacks? In addition to those against whom Dr. Cook warned readers, a more traditional type of quack appears. In 1773 Clarinda writes in with medical recipes to treat diseases in birds, poultry and water-fowl, particularly distemper in Guinea fowl (IV, 239).

Dr Jenny DiPlacidi

School of English, University of Kent