A meteoric rise

A credit default swap (CDS) is a bilateral contract between a buyer and seller of compensation for a fixed maturity, usually five years. The subject of the contract is another entity, like a corporate company or sovereign country, which is called a single-name or name for short. Hence, the buyer is looking for a counterparty that is willing to compensate the market-marked losses on existing bonds with maturity longer than the maturity of the CDS and that is senior unsecured, that is high enough in the hierarchy of bonds issued by the name but also risky.

Thus, a company say ABC may enter with a bank XYZ into a CDS contingent on JKL name. During the life of the 5-year CDS on JKL, if an event occurs such that an existing senior unsecured bond issued by JKL loses say 60% of its value then XYZ will pay ABC 60% of the notional on which the CDS is written. In exchange the seller of CDS is asking for a periodic fee, quarterly or semi-annually usually, until the time of default event. Upon default, the two parties engage in the termination payment and the contract ceases to exist.

As you can see the CDS is defined by a triangle: the ABC is the buyer, the XYZ is the seller and the JKL is the name in the contract. These contracts evolved from a nascent state at the beginning of 2000s to a meteoric notional value reaching trillions of USD in only a few years before the subprime crisis of 2007.

Now I am going to demystify some of the most common misconceptions about this contract, pointing out the advantages and disadvantages and asking some questions related to its recent evolution or devolution.

First of all the CDS is often discussed as a type of insurance contract, providing protection against problems emerging from the name. But there are some important distinctions between insurance and CDS. In an insurance contract the claimant cannot have multiple claims against the same loss, whereas a market participant may enter into a CDS with many counterparties on the same name. In the aftermath of the subprime crisis we found out that the total notional for all CDS outstanding on corporate names was approximately double the notional for all bonds outstanding of those companies! Clearly the CDS helped transform the investing game into a speculating game while calling this activity “buying protection”. For insurance, the seller who provides protection is managing the risk at the portfolio level, looking for many contracts of the same kind. For a CDS the valuation depends very much on the counterparty in the contract and the likelihood of the risk associated with the name. In other words, for a CDS there is a triangle of entities to consider whereas in an insurance contract there are only two parties.

An insurer is looking to use the law of large numbers and get things right on average. A CDS seller, on the other hand, must consider bespoke risk analysis. Furthermore, the CDS can actually be shown to produce the same financial economic gains as a synthetic bond. Selling a CDS to ABC is equivalent to buying a bond from ABC with funding being decoupled. Therefore, a CDS should be recognised as a synthetic bond, first and foremost. This could be helpful in the case of tech companies that do not have debt; Microsoft did not have debt in their ascent so an investor could not invest in Microsoft bonds because they did not exist. AIG played the role of reinsurers for many CDS market-makers and sellers but could not maintain an equilibrium as in insurance markets, with spectacular losses far beyond what has been seen with insurance products.

The most confusing element of the CDS though is the termination event. The event can be of several kinds from a pre-specified list agreed on the market. Thus, the default event includes but it is not restricted to bankruptcy. The company JKL may default on one of their major bonds or they may have other issues such as obligation acceleration, obligation default, failure to pay, repudiation/moratorium, restructuring but they do not go bankrupt. In the end, it is the activity of the JKL market participant that triggers the termination payment of the CDS between ABC and XYZ. To complicate matters even more, JKL could also be a country, say Argentina, in which case the concept of bankruptcy has a different meaning.

Neither does the risk change sides symmetrically. For the seller, unless there is an event, the only risk that they are facing is that the counterparty will stop paying the premium, but then, if that happens, the contract stops. For the buyer, the longer they pay the premium the higher the counterparty risk.

Decline and fall

One of the main problems of the CDS as an asset class was the inexistence of a forward contract. Traders calibrate their models to market trades and forwards/futures are routinely used in other assets classes like commodities, foreign exchange, equity and bonds, to decide today on model parameters that reflect the forward-looking view of the market. The CDS was a contract that had a prospective feature in that the fee paid by the buyer would continue until the maturity of the contract or a termination event. However, that was and is decided on how the market sees things today. A constant maturity credit default swap addressed this dilemma although it was rather timidly bespoke traded in 2006-07 and then sort of disappeared. Without a forward–looking compass, then, traders could not see where the credit risk market was going. Indeed, there is some evidence (for example, Leccadito, Tunaru and Urga, Journal of Banking and Finance, 2015) that forward rates could have helped stabilize the trading on CDS single-name markets.

Any market that attracts a lot of business and large turnover will try to improve its efficiency over time. Credit markets were no different, particularly on corporate names. The indicators of where the credit market was at any one point in time were credit indices, which were built on a sample of the most traded 125 names, say, in a given economy. If an index was going up it was a signal that a name was about to blow up or that there was a lot of turbulence in a sector or economy. Banks started trading credit indices, taking a more macro view regarding credit.

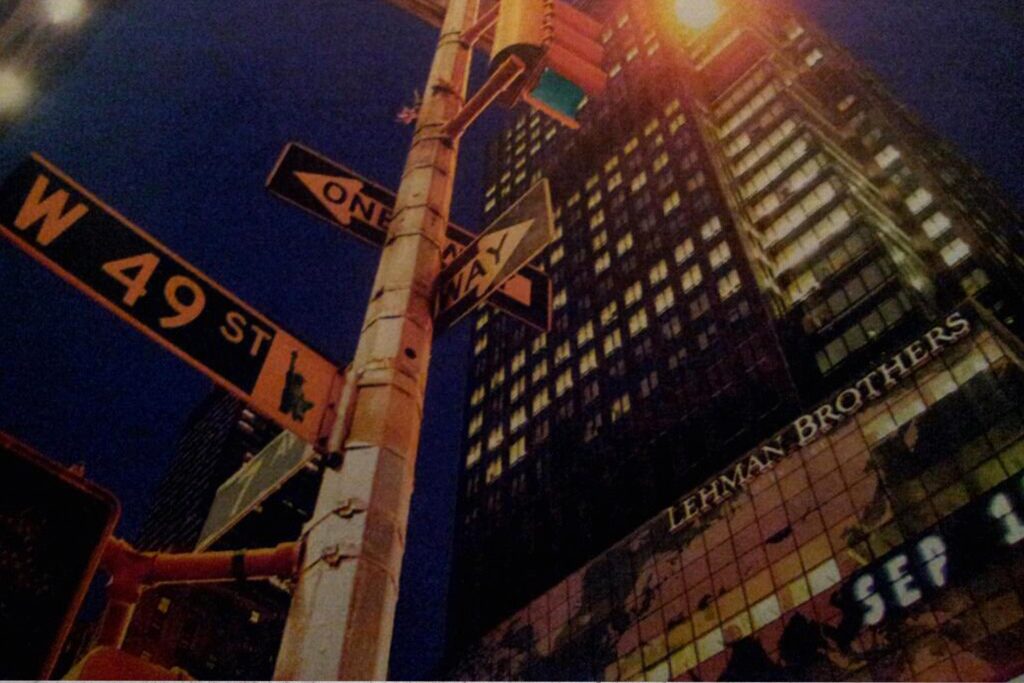

The CDS contract had little to do with subprime mortgages and their subsequent crisis. Once the banks competed in reporting higher and higher losses, the many CDS contracts written on those names suddenly became vulnerable. The demise of Lehman Brothers triggered a lot of activity in CDS markets. Yet, there is no clear evidence whether CDS contracts contributed to the subprime and liquidity crises of 2007-2009 even if they did signal massive problems with several sovereign names.

CDS single-name trades are disappearing, with banks preferring to keep only credit index positions. They proved difficult to hedge, most operators hedging their CDS book with trades on credit indices that were more liquid. The latest Basel set of regulations also attaches high risk factors to them. This means that the CDS market is now experiencing devolution. In many ways, this is absolutely flabbergasting. If banks are not interested in market making single-name CDS trades who will? And if there are no liquid single-name trades how are the credit indices going to be constructed?

Interestingly, this market may be reinvented in China where regulations require that the buyer needs to hold the bond of the name that is trading. That should deter speculation and allow credit risk to be distributed to more participants through the financial markets.

The CDS contract looks now like a lost opportunity. This was an innovative product, simple to understand, and not very difficult to trade. It reveals very important information about the credit riskiness of various business and countries and most importantly it updated this information on a daily basis. The premium charged absorbed a liquidity premium so one may argue that the pure credit risk premium was still difficult to disentangle, but overall it provided a lot of useful information that was simply not there in the 20th century.

The CDS is not of course without dangers. If speculators increase trading on a CDS they may drive the CDS premium for the name up, and if the name then tries to access the financial markets for a loan they could face increased borrowing rates. Bad rumours might transform into self-fulfilling prophecies. The same phenomenon may occur with a sovereign name. CDS on some southern European countries may imply rather than reveal that there will be imminent problems with that country. Of course, investors may switch their investments elsewhere and avoid losses. On the other hand low CDS rates may also induce a sense of extra security about those names. What is the CDS rate of a safe investment? Nobody knows. Let’s hope that somebody cares. And one last important question. Should the seller use its own CDS curve to calculate the fair premium on a new CDS? After all the market does not say that there is any entity that is free of risk.

Professor Radu Tunaru

Director of Centre for Quantitative Finance Research (CEQUFIN)

Director of Centre for Quantitative Finance Research (CEQUFIN)

Professor Radu Tunaru has been working in Quantitative Finance since 2000 and he specialises in Structured Finance (credit risk), Derivatives Pricing and Risk Management, Financial Engineering, Real Estate Finance and Model Risk.