Rob Cowen is an award-winning journalist and writer. He received the Roger Deakin Award for his first book Skimming Stones and Other Ways of Being in the Wild, and read for us this week from his second, Common Ground. He began with a reading ‘from the beginning, which is a very good place to start.’ His reference to Alice in Wonderland set us burrowing into his own wonderland that was to follow, of March Hares (male and female, not male and male), Tarka the Otter, anthracite hills and silvergold sunrises.

Common Ground is a book about the liminal, circling around Bilton, a patch of edge-land just outside Harrogate. It also seeks the subliminal, excavating layers of existence: the human layers of railways, royal hunting grounds and redundancy in the recession, in a ‘world where fractions of other fractions being bet against other fractions by guys in a glass tower in Canary Wharf’; of watching a fox and documenting its smells, movements, and motivations; of lying in a hollow, senses alive to sunlight and sound, eroding the distance between human and nature in a visceral, fragile moment of connection with a roe deer; of discovering, through becoming a father, that the distance between the green of ‘nature’ and the pink and red of flesh and blood is non-existent.

Seeking a place of retreat, Cowen ranges off to ‘relentlessly’ explore his edge-land; not to journey as a pilgrim, nor as the writer of a field guide, stating the density of hair follicles on an animal’s fur, Latin names for plants, or specifying species, but as a forensic investigator of place, as if divining by sense and words what had flowed through there before. He wrote, he said, 150,000 words of notes before even beginning the book. In this next reading, we hear him tracking a fox on a cold January night.

Following the fox, the map became ‘cluttered, complicated and different.’ Cowen talked with enthusiasm throughout, from comparing the paired “Twit” and “Woo” of Tawny owl calls reverberating around hills to ‘something from a Phil Spector record’, to seeing the land as a ‘prism’ through which to view ‘different times and human conditions’ of life past and present, whether it be animal, shrub or person. This merging of of viewpoints draws ‘new maps’ of connections between people and nature, and Cowen finds these by going through the edges, whether psychological, geographical or historical. His final reading enters the realm of humans-as-animals and animals-as-humans, while rejecting a ‘Disney’ anthropomorphism; he enters the mind of the deer that jumped his body, and then allows that deer, in turn, to embody the man that hunts it. The book goes beyond the classifications of genre (something of a running theme in this term’s Reading Series), blurring the bounds and edges between memoir, fiction and non-fiction.

Afterwards there was time for questions and Cowen explained how, in Common Ground, he was looking to ‘pull about’ the dividing line between man and nature. He pointed to plant pots, paintings of landscapes, and nature television programmes to demonstrate a need to be close to nature and of how the line is not finite and concrete, if it even exists. He repeated his desire to write a ‘sense of place’ rather than a guide to viewing it. He went to extemporise on Hares, Easter eggs, land legislation and the birth of his child.

Cowen described the difficult process of reducing words down, of chiseling at them with hard work to make them into the final book. He finished by talking of the metre of a line of text, and of how if it doesn’t deliver a sense of the place it is describing, it has no purpose. This desire to communicate a rich and textured sense of a place is what energised his prose and his energetic, informed and passionate discussion of the book.

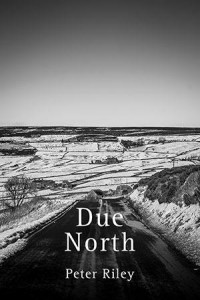

Due North, a fascinating collection of philosophical landscape poems that present the reader with a series of images

Due North, a fascinating collection of philosophical landscape poems that present the reader with a series of images