Dr Kate Rennard (University of Kent)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

This is the latest in the series of blog posts commemorating Indigenous North American participation in the World Wars – see previous posts from November 2018, June 2019 and November 2019. Around 44,000 American Indians and at least 3,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples saw active duty in the Second World War (the real number is undoubtedly much higher).[1] To commemorate the 75th anniversary of V.E. Day, this blog-post spotlights the stories of several of these veterans about the end of the war in Europe.

On the evening of May 8th, 1945, Sgt Leroy Mzhickteno, a Prairie Band Potawatomi from Kansas, was in France. Making his way back to his unit with a fellow soldier, they passed another camp where celebrations were in full swing. As he laughingly recalled in an interview for the Veterans History Project, it ended up being quite an end to his time in Europe:

“[The other soldier] said, ‘let’s check that place out.’ There was no fighting, no nothing, you know, so I said, ‘Okay, something to do.’ Went down there and them guys down there were dancing and having a good time, you know. War’s over. And they’re ‘Come on! Come on!’…And one guy was making a drink for us. He fixed it right there…It was not like anything I ever tasted! It had more kick to it… Oh man, I don’t remember ever getting back to camp…I lost my hat and my ammunition belt was gone. I was in bad shape…Nobody had any sympathy for me!”[2]

This kind of joyous celebration is what many of us associate with V.E. Day, those iconic photos of huge crowds, street parties, and bunting to commemorate the end of the war in Europe. As James Brady, a Metis soldier from Alberta, Canada, noted in the diary he kept during his time fighting in Northern Europe, “At last the wondrous day. Victory in Europe.” However, Brady’s diary is also a window into the variety of competing emotions elicited by the end of the war. To his unit, this day was actually an “anti-climax,” a time for more somber reflection: “There is no feeling of exultation, nothing but a quiet satisfaction that the job has been done and we can see Canada again.” A day later, the unit marched to a “memorial service in the little rural church” to “commemorate those of our regiment who fell in the campaign.” As the Colonel began to read the 36 names, he began to falter and cry. His assistant stepped in and quietly said, “‘It is not necessary. They were comrades. We remember.’” While V.E. Day was certainly worth celebrating, Brady acknowledged how bittersweet it was, especially when so many fellow soldiers were unable to celebrate it with them.

For these Indigenous North American soldiers who were still on the battlegrounds of Northern Europe when the war ended, the brutal reality of the conflict and what victory had cost was inescapable. Nurses such as 1st Lt Marcella LeBeau (Cheyenne River Sioux) and 1st Lt Julia Nashanany Reeves (Forest County Potawatomi) were still working in hospitals in Liege, Belgium and Norwich, England respectively, tending to injured soldiers.[3]

Francis William Godon (Metis) had just been liberated from his Prisoner of War camp. Taken prisoner by German forces shortly after D-Day, Godon spent eleven months in captivity and his weight dropped by almost 100lbs.[4] He remembered the chaos of the days leading up to V.E. Day, as guards deserted the camp. The prisoners woke up to find them gone and the gates wide open. American troops arrived shortly after to liberate them.[5] Other soldiers making their way home to the United States or Canada marched through countryside scarred by the fighting and encountered destruction on a large scale. In some cases, they even caused more damage. Brady recounted how the troop had spent the night of V.E. Day at a farmhouse. Unfortunately, the troop’s kitchen burner had exploded and “burnt the building to the ground.” Brady “could not help but feel pity for this peasant family” who had lost so much and now lost what little they had left.

A few days later, Brady’s unit arrived in Markelo and he continued to reflect on how V.E. Day had been far from a celebration for some. His entry for May 13th discusses the actions of the Dutch resistance: “Five thousand Dutch SS are in cages at Utrecht. In Markelo we see a little Dutch girl almost a child with clipped hair and pregnant – what an aftermath of war, wholesale misery – we witness the sadistic emotions of revenge and it sickens the human spirit.”[6] He wished for a letter from home to keep himself from “baneful thinking.”[7] Clearly, these Indigenous North American servicemen and women were shaped in a variety of ways by their experiences in Europe during the conflict.

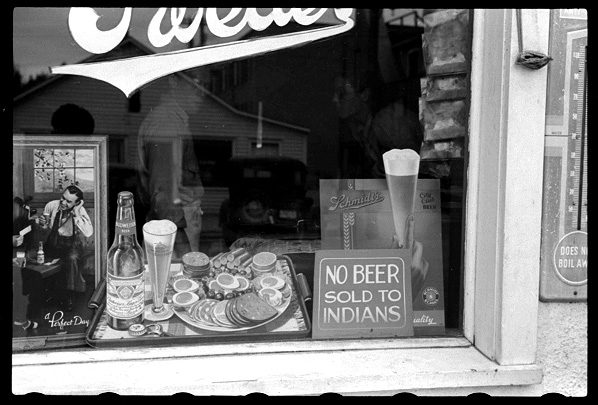

Despite their service, however, they returned home to find that not much had changed. Hollis Stabler (Omaha) recalled that when he returned to Omaha, Nebraska, he headed to a bar for a beer and a hamburger but “somebody called the police.” A policeman arrived and told Stabler that he shouldn’t be drinking so he “just dropped the bottle and walked out.” He was still in his uniform but that hadn’t mattered. As he reflected, “[i]t made me wonder what I’d been fighting for. I never went back to that place.”[8]

Likewise, Marcella LeBeau recalled the racism she encountered when she returned to Rapid City, South Dakota, to work as a nurse after the war:

“I never experienced any discrimination at all in the service. They accepted me for what I was able to do. And then I come back to South Dakota, my state, and saw the sign [bars and restaurants in the city had signs that said ‘No Indians or dogs allowed.’]. And the law was that anything that had alcohol in it, we couldn’t buy, like even vanilla extract with alcohol in it, or rubbing alcohol. I went to a drug store at home to buy some rubbing alcohol and the lady, the dignified lady in the city of Mobridge, she said, ‘We don’t have any.’ So I went back to the grocery store where I traded and knew the man. ‘Well, that’s strange,’ he said, ‘at a drug store.’ So he went over there and he bought me two bottles. So she lied to me.”

These veterans had served in the U.S. Army but when they returned home they couldn’t even buy vanilla essence.

Similar to those who had fought in the First World War, these veterans’ experiences during the war and when they returned home led them to fight for better rights.[9] Dick Patrick (Saik’uz First Nation) was honoured with a Military Medal for his bravery and, during his investiture at Buckingham Palace in October 1945, he spoke to King George VI about the treatment First Nations people faced in Canada: “I told [King George VI] when my people went into Vanderhoof [the nearest town to his community], they were not allowed to go into restaurants, use public toilets, and had to come in the back door of a grocery store to buy groceries. We spoke for a long time about the injustice to my people. He told me he would endeavour to help my people.” His commitment to bringing attention to this discrimination continued after he returned home to British Columbia in 1946. On his first visit to Vanderhoof, he went to a café that was known to refuse service to Indigenous people. When he was told to leave, he refused and the police were called. Patrick was arrested, charged with disturbing the peace, and eventually sentenced to six months in prison. Thanks to local Indigenous activists, he was shortly released and he headed straight back to the same café. As he later recalled, “in one year, I spent 11 months in prison. I would just get off the bus and walk into a restaurant and they would send me back…. I was bound and determined to show them they could not treat my people like animals.” While he never got his meal at the restaurant, his sister remembers that his protest made a huge difference, waking “everyone around him up to the realities of the world we were living in.”[10]

The experiences of these Indigenous North American servicemen and women were diverse, from soldiers in the U.S. and Canadian Armies who were fighting on the Front to nurses to a Prisoner of War kept captive at a camp in Germany, yet all gesture towards the complicated mixture of emotions elicited by the Allies’ victory. While acknowledging the joy of the war ending, each of them also reflected on the huge emotional and physical costs of the conflict, as well as what it meant to return to societies where their service meant little.

If you have any information about Indigenous North American visitors to Britain that you would like to share, please contact us via email, Twitter, or Facebook, or visit our website.

[1] “Patriot Nations,” National Museum of the American Indian, accessed 5 June 2019, https://americanindian.si.edu/static/patriot-nations/world-wars.html#ww2; “Indigenous People in the Second World War,” Veterans Affairs Canada, accessed 5 June 2019, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/aborigin

[2] Leroy Mzhickteno Collection, (AFC/2001/001/38223), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

[3] Unknown, “Lt. Julia (Nashanany) Reeves receiving Ward 53rd Evac Hospital, New Caledonia, with destroyed Japanese flag,” UNO Digital Humanities Projects, accessed May 7, 2020, https://unodigitalhumanitiesprojects.omeka.net/items/show/45.

[4] Jules Xavier and Shilo Stag, “Francis William Godon 1924-2019 Métis D-Day Veteran Passes 75 Years After Harrowing Experience at Juno Beach,” Government of Canada, 26 February 2019, accessed 3 May 2020, http://www.army-armee.forces.gc.ca/en/news-publications/national-news-details-no-menu.page?doc=francis-william-godon-1924-2019-metis-d-day-veteran-passes-75-years-after-harrowing-experience-at-juno-beach/jskwaa54.

[5] “Veteran Stories: Francis William Godon,” The Memory Project, http://www.thememoryproject.com/stories/539:francis-william-godon/

[6] For more on how head shaving has been used as a tool of humiliation against female collaborators, see Antony Beever, “An Ugly Carnival,” The Guardian, 5th June, 2009, accessed 7th May, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/jun/05/women-victims-d-day-landings-second-world-war.

[7] James Brady,“Jottings from a Record of Service in the North West Europe Campaign July 9th, 1944-May 8th, 1945,” M-125-1, James Brady fonds, Glenbow Archives, Calgary, https://www.glenbow.org/collections/search/findingAids/archhtm/extras/brady/m-125-1-pt2.pdf

[8] Hollis D. Stabler, No-One Ever Asked Me: The World War II Memoirs of an Omaha Indian Soldier (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 122.

[9] For more on Indigenous veterans activism after the Second World War, see R. Scott Sheffield and Noah Riseman, Indigenous Peoples and the Second World War: The Politics, Experiences and Legacies of War in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[10] Jason Permanand and Steve McCullough, “Dick Patrick: An Indigenous Veteran’s Fight for Inclusion,” Canadian Museum for Human Rights, https://humanrights.ca/story/dick-patrick-an-indigenous-veterans-fight-for-inclusion.

Thank you for this, Lydia. It is deeply shocking the way Indigenous soldiers were often treated on their way home. They – and their families and communities, of course – gave so much both for Canada and the UK (and the USA) in both world wars, but were rarely given the respect or gratitude they deserved.

Upon return to Canada our Metis veterans were dropped off in Winnipeg Manitoba and had to walk hundreds of miles back to Cumberland House Saskatchewan. That’s the treatment our courageous uncles were treated.