As we approach the centenary of the Armistice, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ is highlighting Indigenous North Americans’ experiences in Britain during the First World War with a series of short profiles. These pieces are snapshots of some of the stories we have found so far and are not meant to be representative of Indigenous peoples’ experiences of the conflict. If you have any information about Native North American visitors to Britain that you would like to share, please contact us via the links at the end of this post.

LEGACIES

“I regret that the funds at our disposal are so limited that we are not in a position to treat returned [First Nations] soldiers as generously as the whites are treated by the Allowance Committee of the Pension Board.” – Harold McGill, Deputy Superintendent General of the Department of Indian Affairs, 1933[1]

For Indigenous North American people who served in the First World War, the legacies of that service were diverse. While often welcomed back as heroes, they had to deal with the physical and mental injuries suffered in the line of duty, the limited range of jobs available to them on their return, and whether they were returning home at all (some chose to stay in Britain for various reasons). For those who did return home, they also encountered issues that were related to their status as Indians, including racism and settler colonial government policies designed to erode tribal sovereignty. Today, we remember a soldier and a nurse (both Mohawk) whose experiences provide a window into some of these complicated legacies.

Angus Goodleaf (Mohawk)

Private Goodleaf was born on the Kahnawá:ke Mohawk Reserve in what is currently Quebec in 1897. He enlisted in 1916 with the 114th Battalion, training alongside John Stacey and Chief Clear Sky (see below). He didn’t join them on their visit to Scotland, however, as he was seriously ill at Moore Barracks Hospital, Shorncliffe, with pneumonia.

Goodleaf was sent to the Front in January 1917 and was injured at Vimy Ridge in June. After being invalided back to Britain, he spent time in hospitals in Derbyshire, Leicester, and Epsom, where he was treated for gunshot wounds to his chest, thigh and knee. He was eventually transferred back to Canada and discharged due to his injuries.

When Goodleaf returned to his reserve, he found that help from the government was not as readily available to him as to white soldiers. As mentioned briefly in the opening blogpost of this series, First Nations soldiers often had problems accessing the veterans’ benefits to which they were entitled. They usually couldn’t attend their local branch of the Royal Canadian Legion because it served alcohol and the Indian Act prohibited First Nations people from entering premises where alcohol was available for purchase. As a result, many Indigenous veterans did not have access to information or advice to help them in applying for their benefits. Goodleaf, however, contacted his former Commanding Officer, Col. Andrew Thompson, in the early 1930s to intercede on his behalf. The response Thompson received exposed further inequalities that were a direct result of who was responsible for distributing the aid. According to a letter received from Harold McGill, the Deputy Superintendent General of the Department of Indian Affairs, the Pension Board had objected to their “being obliged to look after the interests of Indian pensioners” and so they had passed on the responsibility for veterans who lived on a reserve to the Department.[2] This had serious economic consequences for the veterans involved, especially as the Great Depression took hold. As McGill readily acknowledged, the Department did not have the money to give Indigenous veterans the same level of aid as their white counterparts. In his response, Goodleaf made clear how unjust this was: “Do you believe yourself that is justice? I am asking for no special favours or anything like it as I simply believe we owe the Gov. nothing but they certainly owe us plenty.”[3] As Goodleaf’s letter suggested, many Indigenous veterans, particularly those who lived on a reserve, felt that they had served Canada in her time of need but that the country gave them nothing in return.

Edith Anderson Monture (Mohawk)

Edith Anderson was born on the Six Nations Reserve in what is currently Ontario in 1890. Since First Nations’ women were excluded from nursing programmes in Canada, Anderson trained in New York and graduated in 1914. She volunteered with the US Army’s Nursing Corps in 1917 and shipped out in early 1918. Anderson and her unit arrived in Liverpool on 4th March, 1918, before making their way to Southampton and then sailing for France. Stationed at Buffalo Base Hospital 23 in Vittel, France, Anderson nursed thousands of injured soldiers and was often close to the fighting. As she recalled in an interview in 1983, “We would walk right over where there had been fighting. It was an awful sight—buildings in rubble, trees burnt, spent shells all over the place, whole town’s blown up.”[4] After the war, she returned to the Six Nations Reserve and continued to work as a nurse. She died in 1996 at the age of 105 and was given a military funeral as the last First World War veteran on the reserve.[5]

Anderson’s experience illuminates another aspect of Indigenous veterans’ post-war lives – voting rights. Under the Military Service Act of 1917, she gained the right to vote in federal elections without giving up her status as an Indian. As such she was the first female status Indian and registered band member to do so. Routes to Canadian citizenship had been available before this but not without renouncing Indian status. As such, it was often seen as an attempt by the settler government to assimilate Indigenous peoples and erode tribal sovereignty. It was not until 1960 that the vote was extended to status Indians without having to give up their rights as Indians, making Anderson one of the few women on the Six Nations Reserve who could vote for over forty years. Likewise, in the U.S., Native veterans who had been honorably discharged could apply for citizenship and its associated voting rights after the 1919 Indian Citizenship Act. Yet this was not universally appealing. As Diane Camurat has pointed out, by 1920, no veteran from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians had applied, despite every one being eligible. Chief Clinton Rickard (Tuscarora) mentioned having the same concerns as First Nations about citizenship: “United States citizenship was just another way of absorbing us and destroying our customs and our government…How can a citizen have a treaty with his own government? To us, it seemed that the United States was just trying to get rid of its treaty obligations and make us into taxpaying citizens who could sell their homelands and finally end up in the city slums.”[6] While the US and Canadian governments saw citizenship as an aspiration for Indigenous peoples and part of their larger assimilation policies, Indigenous veterans clearly considered it problematic at best.

For many veterans, the problems they encountered on their return strengthened their resolve to improve conditions for Indigenous North Americans and many of those we have profiled in the last two weeks were active in campaigns for Indigenous rights in the post- war years. Francis Pegahmagabow, for example, served as Chief of the Wausauksing First Nation from 1921-25 and campaigned against Indian agents’ authority over tribal councils. Similarly, Onondeyoh Loft founded the League of Indians in Canada in 1918 and argued that First Nations needed to “free themselves from the domination of officialdom.” After retiring from performing, Tsianina Redfeather was a founding member of the American Indian Education Foundation. Consequently, many of the activist efforts concerning Indigenous rights that developed in the inter-war years had a foundation in the complicated and diverse experiences of Indigenous North Americans who served in the First World War.

[1] Quoted in Stephen Smith, “Wounded after Vimy, Kahnawake veteran found white privilege still ruled back home,” CBC, accessed November 11, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/wounded-after-vimy-kahnawake-veteran-found-white-privilege-still-ruled-back-home-1.4071241.

[2] Stephen Smith, “Wounded after Vimy, Kahnawake veteran found white privilege still ruled back home.”

[3] Quoted in Brian MacDowall, “Loyalty and Submission: Contested Discourses on Aboriginal War Service, 1914-1939,” in The Great War: From Memory to History, ed. Kellen Kurschinski et al (Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2015), 207.

[4] “Nurse Overseas,” Veterans Affairs Canada, accessed November 11, 2018, http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/those-who-served/aboriginal-veterans/native-soldiers/nurse.

[5] For more information on Edith Anderson’s life, see Laurence Hauptman, “On the Western Front: Two Iroquois Nurses in World War I,” American Indian, accessed November 11, 2018, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/western-front-two-iroquois-nurses-world-war-i.

[6] Diane Camurat, “The American Indian in the Great War: Real and Imagined,” accessed November 11, 2018, http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/comment/cmrts/Cmrt8.html.

Cora Elm (Oneida)

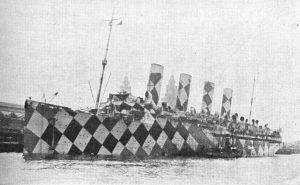

Cora Elm, an Oneida from Wisconsin, was born in 1891 and graduated from Carlisle Indian School in 1913. Having trained and worked as a nurse at the Episcopal Hospital in Philadelphia, Elm joined Base Hospital 34 in 1917 (it was also known as the Episcopal Unit as so many of its personnel came from the Episcopal Hospital). She sailed from New York to Liverpool in December 1917 on the Leviathan and arrived in England on Christmas Eve. As the unit’s official history recounts: “On the morning of December 24th, 1917, the Leviathan yawned open her ports to pour forth her cargo of humanity on Liverpool’s massive docks. A few whistles tooted salutation, while a dripping rain made sodden our ebbed spirits. No time was lost.” The unit soon made their way to Southampton via train and the nurses stayed in hotels overnight before sailing for Le Havre on Christmas Day. As Elm recounted, her time in France “was not very easy. Although I was in a base hospital, I saw a lot of the horrors of war. I nursed many a soldier with a leg cut off, or an arm.” Elm continued nursing until her death in 1949.

John Stacey (Mohawk)

John Stacey was born in 1888 on the Kahnawà:ke Mohawk reserve in what is currently Quebec. He enlisted as an officer in May 1916 and arrived in Liverpool in mid-November. As part of the 114th Battalion, he took part in their visit to Glasgow and Edinburgh in December 1916 (for details, see our earlier profile from November 5th) and stayed in touch with some of those he met there. In July 1917, after he had reached France, Stacey wrote a letter to the Lord Provost of Glasgow: “We have naturally suffered some losses but generally I consider we have been fortunate. We are shortly leaving for the front line trenches again, and doubtless there will be some hard fighting so I thought I would write a few lines in order that you might have first-hand information that the…Indians from Canada whom you entertained are now really doing the job for which they came over, and are prepared to see the matter to a finish.” (Daily Record, July 7, 1917) A month later, he suffered gunshot wounds to the face, chest, and thumb during fighting near Lens. Invalided back to the UK, Stacey joined the Royal Flying Corps School of Aeronautics in Reading and became an R.A.F. pilot. Unfortunately, he was killed in an aeroplane accident at Hounslow in March 1918, when the plane he was flying crashed.

Trace his story across two continents here.

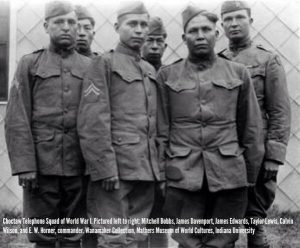

Choctaw code talkers

In October 1918, the Meuse-Argonne campaign was going badly for U.S. troops; their telephone lines had been tapped by the Germans and military codes were being continually broken by the enemy. About a quarter of runners sent out to deliver messages were captured. The answer to the problem came to officers of the 142nd Infantry by chance, when they overheard two Native soldiers in their regiment talking to each other in their Indigenous language. As one described in his memo to Headquarters: “it was remembered that the regiment possessed a company of Indians. They spoke twenty-six different languages or dialects, only four or five of which were ever written. There was hardly one chance in a million that Fritz would be able to translate these dialects and the plan to have these Indians transmit telephone messages was adopted.”[1] Soon 19 Choctaw soldiers had been recruited and placed in key companies and code talking was born. It helped the US Army win key battles because the Germans were unable to understand what was being said even if they overheard messages. The Choctaw language didn’t have words for most military terms so alternative words were invented. For example, a machine gun became “little gun shoots fast.” These code talkers were not only crucial to the Allied offensives in autumn 1918 but also shaped future military tactics – Navajo code talkers would become famous for their role in the Second World War. Yet, as Judy Allen, senior executive officer of tribal relations with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma has noted, the use of Choctaw to help win the war was ironic given that Native children were being sent to federal boarding schools designed to forcibly assimilate them: “You had this crazy situation where the Choctaw language was being used as a formidable weapon of war, yet back home children were being beaten at school for using it.”[2]

Of the Choctaw soldiers of the 141st, 142nd, and 143rd Infantries who contributed to this communications breakthrough, only one came through England: Victor Brown of the 143rd. While the other two units sailed directly to France, the 143rd sailed for Liverpool and then travelled by train to Southampton to sail to Le Havre. Brown received a Presidential citation after being wounded and gassed at the Front and, according to his daughter Napanee Brown Coffman, he was “very proud and pleased that they had ‘fooled the Germans’” by using the Choctaw language.[3]

[1] Quoted in “Choctaw Indian Code Talkers of World War I,” Texas Military Forces Museum website, http://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/choctaw/codetalkers.htm.

[2] Quoted in Denise Winterman, “World War One: The original code talkers,” BBC News Magazine, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-26963624.

[3] Quoted in “Choctaw Indian Code Talkers of World War I.”

Frederick Onondeyoh Loft (Mohawk)

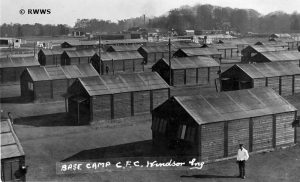

Born in 1861 on the Six Nations Reserve in what is currently Ontario, Frederick Loft, also known as Onondeyoh (“Beautiful Mountain”), was a prominent Mohawk activist who campaigned for Indigenous rights, including closing residential schools, which he called “veritable death-traps.” He enlisted in the Canadian Army in 1917 by lying about his age (he said he was 45 but he was really 56) and sailed for Britain shortly afterwards. After training at Windsor, where the Canadian forces had a base depot, Loft spent five months in France before returning to Britain. (IMAGES: WW1a, CAPTION: A view of the Canadian Forestry Corps base depot at Windsor (Royal Windsor Website), and http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?app=fondsandcol&op=img&id=a004696-v8, CAPTION: Canadian soldiers at work in the Great Park during the First World War (Libraries and Archives Canada)). As a representative of the Grand River Iroquois Confederacy, he met with King George V at Buckingham Palace in early 1918, just before leaving to return to Canada.

Excerpt from Lieutenant Loft’s letter to Colonel Belcher, August 3, 1917 (Ontario Archives)

My dear Col. Belcher,

It is now a month since I and my brother Indians and the rest of our company landed upon real British soil…

We landed safely at Liverpool on the 11th of July after a most pleasant voyage on the Atlantic. It was at no time rough enough to make it exciting. I would like to have seen her roll and toss just to see what it was like. Liverpool was interesting: we stayed there just long enough to disembark and then right to the trains in waiting that hied us to Windsor Park. The King’s Park is a grand spot, where we have been camping, drilling etc. There is really a riot of beauty in the English country side with all its bridges and gardens of flowers by every home. Grand roads for motoring. Houses, lodges and towns & cities look quaint & old-fashioned. There is a quiet dignity about it all.

So far, I have spent four days in London. I visited the Tower of London; it and Westminster Abbey appeal to me much. The Tower is gorgeous in its display of the ancients in implements of warfare, also of the modern. The Crown Jewels are there in their glory and magnificence. Why I could not pretend to [?] what is to be seen there to feast thus upon for days. Truly every British subject who has seen London could not but say every subject of Britain should be more than proud of the greatest city in the Empire.

I visited the Old Bailey. As soon as it became known to the police officers that I was a Mohawk, I was ushered to a place of honour in different courts. I was presented to the Lord Sheriff and he was so kind as to invite me to lunch with him when also were present the judges of different courts and many learned gentlemen of the bar.

I also went to the House of Commons. Met the private secretary of Rt. Hon. W. Long, Sec. of Colonies; also Mr. J. Burns M.P. I was graciously assigned a seat in the gallery for distinguished visitors. There I met an M.P. from Australia, also Agent General of S. Australia. The following day I was invited to Ham House, Richmond, the seat of the Earl of Dysart. It was a garden party. The afternoon there was most delightfully spent in viewing a veritable gallery of art which adorned the whole house. The Earl and Countess were most gracious. I had a real pleasant chat with each. The London press has been more than profuse in the mention and photos of my Indian warriors and myself as the Chief Warrior. They have done us proud.

Under war conditions, this is where my brothers even separate so my warriors and I have been separated. They are gone to France but I am still here but will be with them again I hope ere long. Indeed, yesterday, I was told to be ready to go on a moment’s notice. I am delighted with camp life. My boys were only too eager to proceed to a new field. I am the same. Here, you hardly know yourself – don’t know what next will be as an order. Now my dear chief it is getting dark and wet. Rain every day this week. Best love to you & Mrs. Belcher.

Your friend,

Onondeyoh

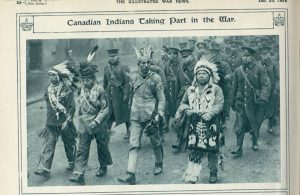

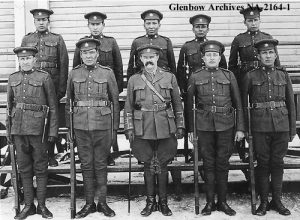

Chief Clear Sky and the 114th Battalion (Iroquois)

In December 1916, a contingent of the 114th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force arrived in Glasgow, Scotland, for a visit. Made up of approximately 165 First Nations soldiers, mainly Iroquois, the troop spent three days touring places such as Glasgow Cathedral and the McLellan Galleries before leaving for Edinburgh. As Private Joe Beauvais remarked, “It’s quite good to be here, and I’m sure we’re quite overjoyed at the fuss you are making of us.” (Dundee People’s Journal, 16 Dec. 1916.)

While the soldiers enjoyed their visit to the Scottish cities, they also made sure to educate the British public about contemporary First Nations. The newspaper articles covering the tour were full of stereotypes, which Chief Clear Sky, one of the leaders, was keen to dispel. Talking to the Dundee People’s Journal, he remarked, “‘You’re not going to ask me whether I’m a trapper or a hunter, are you? ‘Kase I ain’t either. What gets me is folks fancying we Indians must all be trappers and hunters. These days are all pretty well shot up now. I’ve done a whole bunch of things to earn a living. Last thing I did was getting around in vaudeville.’” Shortly after the visit, the 114th was sent to the Front, although some soldiers continued their connections with Scotland. Lieutenant John Stacey, for example, wrote a letter to the Lord Provost of Glasgow in July 1917 to update him on the 114th’s efforts in France and Chief Clear Sky returned to Scotland several times in the following years.

Read more on the visit and its significance in this piece by ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ project associate, Dr. Yvonne McEwen: https://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/chief-clear-sky-and-his-men-made-ultimate-sacrifice-at-the-somme-1-4286126

Tsianina Redfeather (Cherokee/Creek)

Tsianina Redfeather, a prolific singer and performer, was born in Eufaula, within the Muscogee Creek nation, in 1882. In 1917, she travelled to England and France with the YMCA to entertain the troops and her journey was eventful – her ship was torpedoed almost two days out from Liverpool. She made it safely to Britain and was stationed at the YMCA hut in London before heading to France. Redfeather’s shows, in which she dressed in a beaded headdress and buckskin dress, made quite the impression on the British press, who declared her the “Army’s Hiawatha.” Her motivations for performing for the U.S. Army had very little to do with any sense of loyalty to America though. She said: “Here I was – helping defend the homeland which in turn had robbed us of our heritage. Amazing! I wondered if I had all of my marbles!”[1] Instead, her war experience gave her “an even deeper pride in my heart for being an American Indian.”[2]

Redfeather retired from performing in 1935 and she became an activist for American Indian education, helping found the American Indian Education Foundation.

Watch a video of Tsianina Redfeather performing here.

[1] John Troutman, Indian Blues: American Indians and the Politics of Music, 1879-1934 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 238.

[2] Tsianina Redfeather, Where Trails Have Led Me (Burbank, California: Tsianina Blackstone, 1968), 104.

John Shiwak (Inuit)

John Shiwak was born in Labrador in 1889. He worked as a hunter and trapper before enlisting in the Newfoundland Regiment in 1915. He was sent to Scotland for training, where he spent time in the Bladda Infectious Diseases hospital in Paisley while being treated for measles. He reached the Front in July 1916, where he earned a reputation as a talented soldier – one officer called him the “best sniper in the British Army.” He was also well liked by the other men in his company. His military records contain a letter from Captain Robert Tait, in which he wrote that Shiwak “was a great favourite with all ranks, an excellent scout and observer and a thoroughly reliable fellow in every way.” He was killed in action by a German shell at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917 and was awarded the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

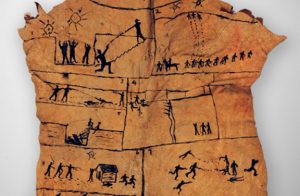

Mike Mountain Horse (Kainai)

Mike Mountain Horse was born on the Kainai reserve in southern Alberta, Canada, in 1888. He had worked as a scout for the North West Mounted Police before enlisting in 1916. His brother, Albert, had died the year before from injuries received in action (he had been gassed three times and was in the process of heading home before he contracted tuberculosis with his badly damaged lungs). Mountain Horse was also injured in action in France several times and recovered in hospitals in Liverpool, Epsom, and Reading, England. He is perhaps most well-known for his buffalo robe drawings of his experience fighting in France.

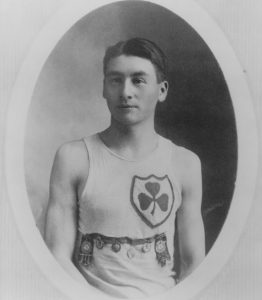

Alexander Decoteau (Cree)

Alexander Decoteau, a member of the Red Pheasant First Nation of Saskatchewan, was born in 1887. He was Canada’s first Indigenous police officer and also a prolific runner. He competed in the 5,000 metre race at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, finishing sixth in the final after suffering leg cramps. Decoteau enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1916 and, after training at Camp Sarcee in Calgary, Alberta, arrived in Liverpool on the HMS Mauretania on 30th November. He spent six months in England before leaving for the Front and wrote letters home to his sister about his experiences in the trenches. He was killed in action by a sniper’s bullet at the Battle of Passchendaele on 30th October 1917.

Like other famous First Nations Olympians who enlisted, including Tom Longboat (Onondaga) and Joe Keeper (Cree), Decoteau served as a dispatch carrier. While their most notorious military exploits happened in France, they were stationed in Britain before going to the Front and they all continued to race during this time. At one event, Decoteau was apparently presented with a gold watch by George V in lieu of a winner’s medal.

Francis Pegahmagabow (Ojibwe)

Francis Pegahmagabow was one of the most decorated Indigenous soldiers in Canadian military history. He was born in 1889 on the Shawanaga First Nation reserve in Ontario and he volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force almost as soon as war was declared in 1914. He was deployed to the Western Front in 1915 and fought in some of its most infamous battles, including Ypres, the Somme, and Passchendaele, earning a reputation as a deadly sniper. It was at the Somme in September 1916 that he received a gunshot wound to the leg that meant he was invalided to hospital in Bristol for several months. He was less than happy about the experience, writing to the Secretary of Indian Affairs: “The reality of soldiering is nothing to me, although I had 20 months under shell fire in France, which I found not half as bad as it is back here in England.” His experience in England may also have been tainted by the legal trouble in which he found himself in August 1915. Appearing in Tower Bridge Police Court on a charge of assault, Pegahmagabow defended his actions from the dock, insisting that “he had handed a sovereign to a woman in order that she might get his flask filled, and that when she gave him the change, he supposed he showed his money too freely, for a number of women surrounded him.” One woman apparently continued to try to steal from him, despite warnings, and so he was forced to act in self-defence (“Indian Chief Charged,” Belfast Telegraph, August 9, 1915). The charges were dismissed. On his return to Canada at the end of the war, Pegahmagabow became an Indigenous rights activist and a leader of his nation, serving as chief from 1921-1925.

[date added: 29/10/2018]

Indigenous North Americans in the First World War

During the First World War, more than 12,000 American Indians served in the U.S. Army (even though around 40% of American Indians were not citizens at the time) and over 4,000 First Nations’ men enlisted in the Canadian forces. The exact number is hard to calculate. In Canada, for example, Indian Affairs lists rarely included Métis, Inuit and non-status Indians (those who belonged to a nation who had not signed a treaty with the government). As Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada has noted, however, these Indigenous soldiers were a significant asset and “served in every major theatre of the war and participated in all of the major battles” in which Canadian and U.S. troops fought. These men and women had various reasons for enlisting, including economic opportunity and patriotism, yet many also thought that their service might help accomplish justice for their nations and communities.[1]

If you have any information about Native North American visitors to Britain that you would like to share, please contact us via email, Twitter or Facebook, or visit our website.

Further Resources

Britten, Thomas A. American Indians in World War I: At Home and at War. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. “Aboriginal Contributions during the First World War.” https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1414152378639/1414152548341. Accessed October 26, 2018.

Krause, Susan Applegate. North American Indians in the Great War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Winegard, Timothy C. For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2012.

—. Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Stories compiled by Dr Kate Rennard, Research Associate on ‘Beyond the Spectacle’.

[1] See Susan Applegate Krause, North American Indians in the Great War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 17.

Important discovery – reference by Six Nations troops of the Great War, to the Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School, in the tunnels beneath Vimy Ridge. http://woodlandculturalcentre.ca/the-mohawk-insti-vimy-ridge-1917/

Mr. Moses, thank you for taking the time to share this with us. My apologies for the mistake on Edith Monture’s year of birth. We have corrected it. Also, Gilbert Monture’s story sounds fascinating! I’ll be in touch again via email.

Aside from great uncle James Moses on my father’s side of the family, my maternal grandmother Edith Anderson Monture (Six Nations of the Grand River Territory) felt the calling to nurse. As described in this blog, Indian Act restrictions of her era prevented her from pursuing her calling in Canada. She undertook her training in the US and was living and working as a public health nurse in New York City when the U.S. entered the Great War in 1917. She volunteered and served 2 years in France with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps of the American Expeditionary Force. She was born in 1890 – not 1891 as described in this piece. Another great uncle was Lt. Gilbert Monture, who served with the Royal Canadian Artillery and was invalided in the UK during the Great War. He was later awarded an OBE following his Second World War service in a civilian capacity (he was a mining engineer and strategic minerals economist who worked in Washington DC on strategic minerals production among the Allied powers).

Mr. Moses, thank you for your comment. I had briefly read about Lt. Moses and Lt. Martin but it would be wonderful to speak with you about them and the other members of the 107th and learn more about their experiences. I will be in touch via email.

I am a member of the Delaware and Upper Mohawk bands, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory near Brantford, Ontario, Canada, currently living and working in Ottawa, Ontario. I am the grand nephew of a number of Six Nations band members who spent time in the UK during the Great War, while serving in the 107th “Timber Wolf” Battalion and 114th Battalion, “Brock’s Rangers”, CEF, before being deployed to France. Lt. James Moses was a close friend of J.R. Stacey, profiled in this piece. Lt. Moses was reported missing, later confirmed killed, while serving as an observer and air gunner with 57 Squadron RAF, on 1 April 1918, just a few days before Lt. Stacey was killed in a flying accident. Another Six Nations band member and pilot who likewise served with Lt. Moses and Stacey was Lt. (later Brigadier) Oliver Milton Martin.