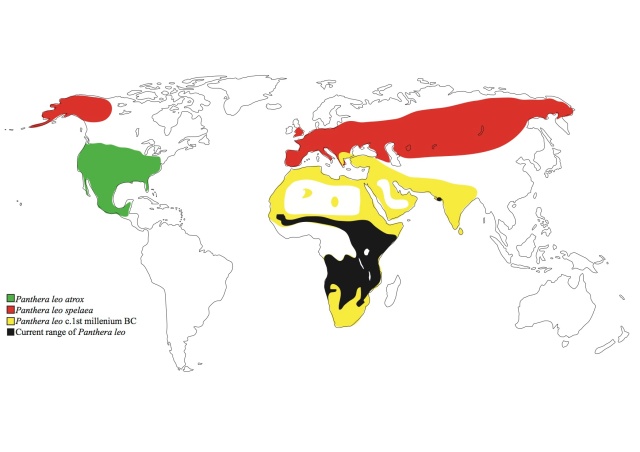

We are familiar with the lions of Africa ranging from Southern Africa up through East African strongholds as well as the smaller populations of central and western African states. There are also Asia’s last lions in the Gir forest Gujarat, India.

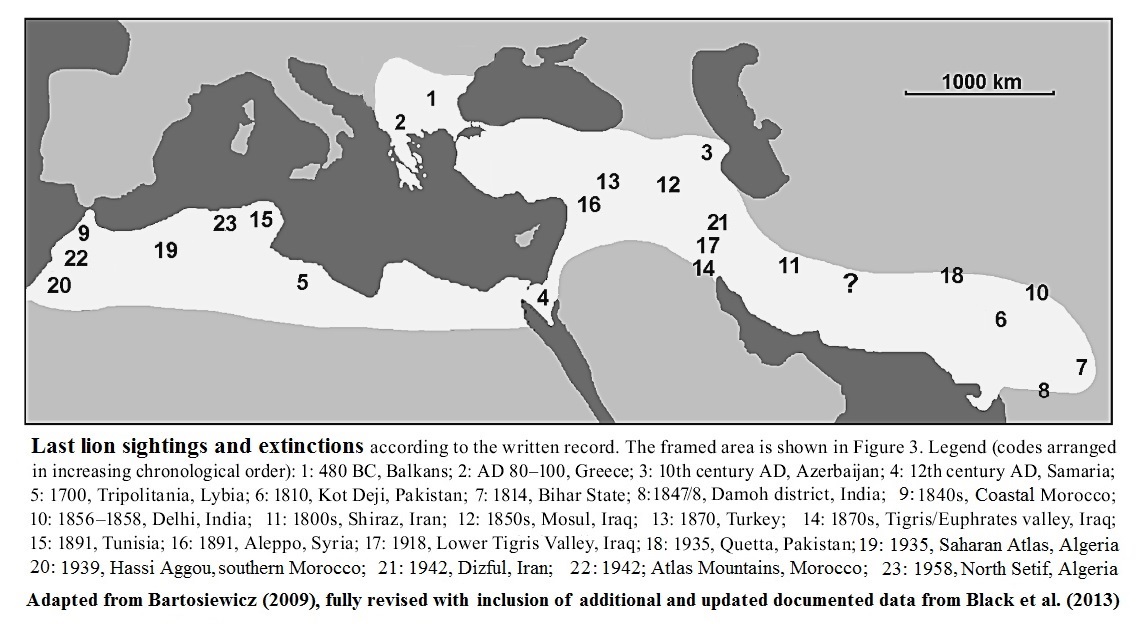

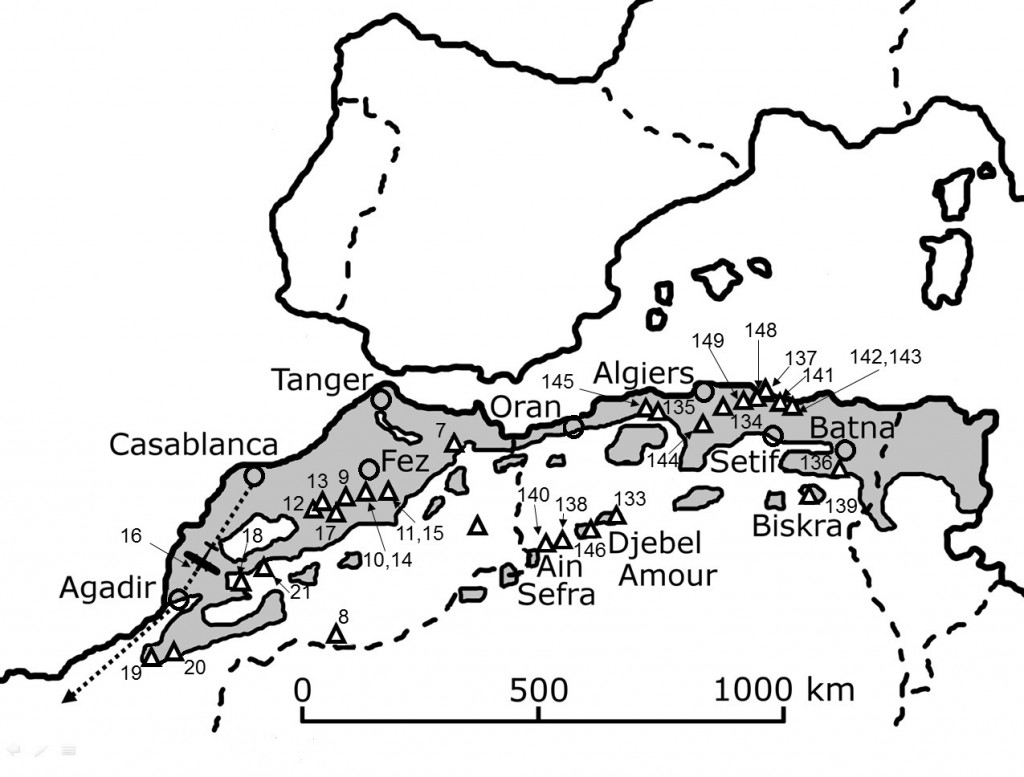

Indian lions are the remnant of a huge former northern range which covered several states across northern India, through to modern-day Pakistan and westward through Iran, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, through the eastern Mediterranean states south of the Sinai desert coast through the western coastal areas of Arabian peninsular, into Egypt, and along the southern Mediterranean coast and mountain ranges of north Africa. They persisted further north in Turkey and Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia until the 19th century. Archaeological studies show they ranged further north along the Black Sea coasts during human prehistory. Intriguingly they still persisted in southern Greece into early historic times as described in Greek literature.

From this vast range today’s picture for lions is much diminished. Genetic studies now show us that the lions of Central and Western Africa are part of this northern population.

When we look at the tens of thousands of lions across Eastern and Southeastern Africa we should not take them for granted. Just ten years ago there were thought to be 40,000. Today perhaps only 20,000. We need to be vigilant in their conservation.

Further Reading:

Bertola, L.D., Tensen, L., van Hooft, P., White, P.A., Driscoll, C.A., Henschel, P., Caragiulo, A., Dias-Freedman, I., Sogbohossou, E.A., Tumenta, P.N. and Jirmo, T.H., 2016. Correction: Autosomal and mtDNA Markers Affirm the Distinctiveness of Lions in West and Central Africa. PloS one, 11(3).

Black S.A. (2016) The Challenges of Exploring the Genetic Distinctiveness of the Barbary Lion and the Identification of Putative Descendants in Captivity, International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. vol. 2016, Article ID 6901892, 9 pages, 2016. doi:10.1155/2016/6901892

Schnitzler, A.E. (2011) Past and Present Distribution of the North African-Asian lion subgroup: a review. mammal Review, 41, 3.