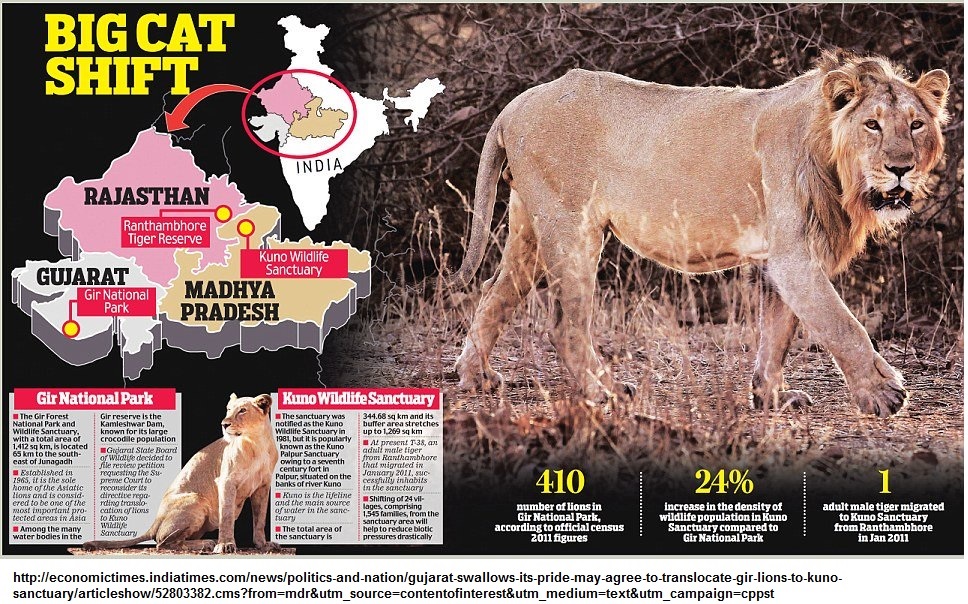

![Documented lion sightings since the middle ages across the Maghreb biome of the southern Mediterranean (light grey shading) north of the Sahara in North Africa (AD1500–1960). Open circles depict locations of general historical observations documented before 1800, adapted from [2]. Details can be sourced from [2, 8, 15]. Asterisks denote the locations of the various named major human population centres.](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/barbarylion/files/2016/09/Fig-2-revised-medium-300x216.png)

Lion sightings since the middle ages across the Maghreb biome (grey shading) of North Africa (AD1500–1960). Open circles depict locations of general historical observations documented before 1800. Details can be sourced from Lee et al (2015), Black et al (2013) and Yamaguchi and Haddane (2002). Asterisks denote locations of the major named human population centres.

This post does not predict the imminent demise of lions but it sends out a clear warning. Despite the 20-30,000 wild lions (mostly in Eastern and Southeastern Africa) let’s examine the circumstances of their survival very closely.

Lions are a relatively long lived species in the wild, so even if rarely-noticed may persist and be re-sighted on an occasional basis, even as individual animals. This appears to have been the case in some recorded sightings of individual lions near the Biskra in Algeria in the early 20th century for instance, with individual animals well-known to locals.

Micropopulations of the animals were identified by Guggisberg (1963) from historical accounts, but these had all disappeared by 1960. The small populations had persisted, but had not bred successfully. The next generation of animals simply failed to materialise.

When we hear of small populations being re-discovered in the Gabon or Ethiopia, we must take this reality into account.

Reading:

Black, S. A. Fellous, A. Yamaguchi, N. and Roberts, D. L. (2013) “Examining the extinction of the Barbary Lion and its implications for felid conservation,” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 4, Article ID e60174.

Dybas C.L. (2016) African Lions on the brink: a conversation with lion expert Craig Packer. National Geographic http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/2016/10/11/african-lions-on-the-brink-a-conversation-with-lion-expert-craig-packer/#.V_-y5k2J-to.twitter

Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1963) Simba: The Life of the Lion, Bailey Bros. & Swinfen Ltd, London, UK.

Lee, T. E. Black, S. A. Fellous, A. et al. (2015) “Assessing uncertainty in sighting records: an example of the Barbary lion,” PeerJ, vol. 3, article e1224, 2015.

Yamaguchi, N. and B. Haddane, B. (2002) “The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas lion project,” inInternational Zoo News, vol. 49, pp. 465–481, 2002