There are perhaps as few as 20,000 lions left in the wild. When I first started studying lions just over a decade ago we thought there were 40,000. Will this figure halve again over the coming 10 years? For a sobering comparison, when I was a child there were 40,000 tigers in the wild; now only around 4,000. The similarity in the lion figures is startling. Decline is real and fearsome.

A comprehensive set of studies of lion genetics has recommended the IUCN to consider the lion family tree as two subspecies. One is the North/West /Central subspecies, Panthera leo leo (which includes lions in West and Central Africa and India, and the previous, now extinct populations in the Middle East, and of course the extinct Barbary lion of North Africa). The second is Panthera leo melanochaita from South and East Africa (i.e. about 90% the world’s population). All remaining ‘northern’ lion populations are tiny and very vulnerable. The ‘southern’ populations are much larger but many animals are cut off from each other in fenced reserves or fragmented landscapes.

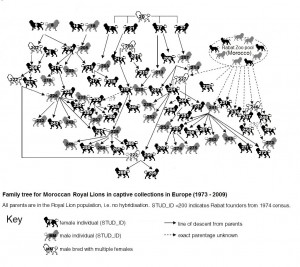

Zoos may have a significant part to play in managing, sustaining and recovering the ‘northern’ subspecies Panthera leo leo. There are around 100 Asiatic (Indian) lions in captivity, but I do not know of a single captive lion from West or Central Africa in any zoo, even in their home countries on the African continent. There are a further 80 captive lions which may be related to the extinct North African Barbary lion. maybe the captive Addis Ababa lions in Ethiopia are linked I some way to this group.

A lion in Addis Ababa Zoo, Ethiopia

Lions are quite long-lived and can persist undetected for decades. This happened in North Africa, where lions had become almost mythical beasts by the late 1890s, but actually survived in northern Algeria into the late 1950s at a time when Gerry Durrell was founding the zoo in Jersey. I often wonder what Durrell might have done had he known that Barbary lions were still out there in the wild… However, this is not a purely historical issue since in 2016 a lion was caught unexpectedly on a camera trap in Gabon, and later confirmed by DNA evidence to be a survivor of a population thought extinct for 20 years – one of the important Central African relic populations of the ‘northern’ lions Panthera leo leo.