Special contribution

Lara J. Bazzu

Worcester Prize Winner 2021, Durrell Institute of Conservation & Ecology

Historical human interaction with lions in North Africa

The “Barbary” lion of North Africa holds particular fascination, being enshrined in cultural emblems of Roman, Medieval, and Colonial periods and in current national identities of the region. As far back as Roman times, Barbary lions were transported from Carthage across the empire for use in gladiatorial games (Yamaguchi and Haddane 2002). Later during medieval times lions were kept in European menageries and their physical attributes inspired paintings and sculpture (Black 2016). The Barbary lion was the first lion type encountered and catalogued by emergent natural scientists of the Enlightenment. By the 1800s and early 1900s North African lions were frequently showcased in zoological gardens (Black et al. 2013) and their remains displayed in stately homes and museums.

The continuous capture and killing of Barbary lions was extensive throughout Roman, Arabic, Turkish and European colonial periods, enduring well into the 19th century (Peterson et al. 2014) By the 1920s, the lions of North Africa were generally considered extinct in the wild (Black et al. 2013). Captive individuals were still kept in the gardens of the sultan of Morocco towards the late 1800s (Burger and Hemmer 2005) and these are often referred to as the Moroccan royal lions (hereafter Moroccan lions). Remarkably, the latest evidence suggests wild lions actually persisted in small numbers in North Africa until the late 1950s or early 1960s before dying out (Black et al. 2013).

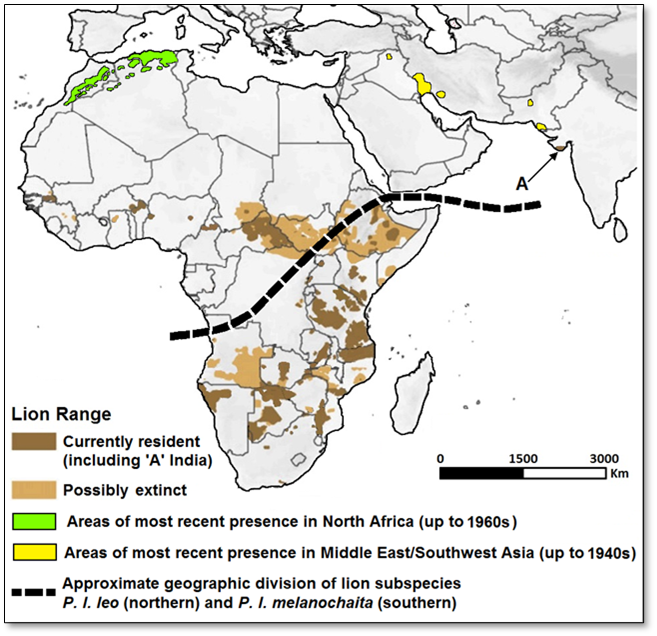

Figure 1. Current distribution of lions (Panthera leo) in sub-Saharan Africa and India, plus 20th century locations of the last populations in North Africa, the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Adapted from: Black (2016).

Historically, the range of lions (Panthera leo) spanned across Africa, the Middle East and southwestern Asia (Black 2016). In 2017 the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recognised two revised subspecies of lion (Figure 1): Panthera leo melanochaita in Southern and Eastern Africa and Panthera leo leo which includes lion populations found in India, Central and West Africa and those which formerly inhabited North Africa, the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula and Southwest Asia (Kitchener et al. 2017). As previously seen in North Africa, remaining lion populations are now in serious decline across Africa with estimates suggesting a shocking 43% decrease in the period 1993-2014 (Black 2016).

Current threats to lions worldwide

Today the only real strongholds for lions are in Eastern and South-Eastern Africa, whereas across Central and Western Africa only micro-populations (some as few as 5 or 10 animals) remain under threat of extinction while in Asia, a small population still persists in India (Black 2016). At present, globally, there may be as few as 20,000 lions (Trouwborst et al. 2017), a frightening reduction from the 500,000 individuals in the 1950s (Frank et al. 2006). More worryingly, of the last 60 recorded populations of lions, only six have more than 1,000 individuals (Trouwborst et al. 2017), the minimum threshold for a sustainable population (Black 2016). Lions are declining due to habitat loss, reduction in prey, direct killing by humans (e.g. to protect livestock), unregulated trophy hunting and a surge in trade of lion body parts (Trouwborst et al. 2017). The effects of climate change are predicted to increase existing pressures, alongside a rise in the frequency and severity of diseases (Peterson et al. 2014). Even fences are a problem in Eastern and Southern Africa where nominally large populations are divided into isolated sub-groups (Trinkel et al. 2017). Unless these numerous threats are addressed, the majority of Africa may become lion-free (Lee et al. 2015).

Lion conservation challenges

Recent reclassification of lion subspecies has identified that almost 90% of lions in the wild inhabit Eastern and Southern Africa, namely the P. l. melanochaita subspecies, while the few survivors of the second subspecies persist in the rest of Africa and Asia (Black et al. 2010). There are possibly fewer than 250 P. l. leo living in West Africa (Barnett et al. 2018), around 400 in Asia and roughly 1000 in Central Africa (Black 2016). In addition, there are barely 100 Asiatic lions in captivity and around 100 captive Moroccan lions (Black 2016). The genetic value of Moroccan lions, should not be underestimated (Black et al. 2013) as they offer a potential ecological link between remaining lions in India and their closest northern subspecies relatives in Central and West Africa (Black 2016).

References:

Barnett, R., Sinding, M., Vieira, et al. (2018). No longer locally extinct? Tracing the origins of a lion (Panthera leo) living in Gabon. Conservation Genetics, 19(3), 611-618.

Bazzu L.J. and B;ack S.A. Les lions d’Afrique du Nord : apprendre du passé pour façonner le futur. (translated C. Guy) Le Tarsier (Association Francophone des Soigneurs Animaliers) 26, 5-9.

Black, S. (2016). The Challenges and Relevance of Exploring the Genetics of North Africa’s “Barbary Lion” and the Conservation of Putative Descendants in Captivity. International Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2016, 1-9.

Black, S., Fellous, A., Yamaguchi, N. and Roberts, D., 2013. Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation. PLoS ONE, 8(4), e60174.

Black, S., Yamaguchi, N., Harland, A. and Groombridge, J. (2010). Maintaining the genetic health of putative Barbary lions in captivity: an analysis of Moroccan Royal Lions. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 56(1), 21-31.

Burger, J. and Hemmer, H. (2005). Urgent call for further breeding of the relic zoo population of the critically endangered Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo Linnaeus 1758). European Journal of Wildlife Research, 52(1), 54-58.

Frank, L., Maclennan, S., Hazzah, L., Bonham, R. and Hill, T. (2006). Lion Killing in the Amboseli -Tsavo Ecosystem, 2001-2006, and its Implications for Kenya’s Lion Population. [Online]. Living with lions. [Accessed 14 August 2021] http://www.livingwithlions.org/annual-reports.html

Kitchener A. C., Breitenmoser-Würsten Ch., Eizirik E., et al. (2017). A revised taxonomy of the Felidae. [Online]. Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN/ SSC Cat Specialist Group. Report number: 11. [Accessed 14 August 2021]. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf

Lee, T., et al. (2015). Assessing uncertainty in sighting records: an example of the Barbary lion. PeerJ, 3, e1224.

Mazak V. (1970). The Barbary lion, Panthera leo leo (Linnaeus, 1758); some systematic notes, and an interim list of the specimens preserved in European museums. Z Saugetierkd 35,34-45.

Peterson, A., Radocy, T., Hall, E., Kerbis Peterhans, J. and Celesia, G. (2014). The potential distribution of the Vulnerable African lion Panthera leo in the face of changing global climate. Oryx, 48(4), 555-564.

Trinkel, M., Fleischmann, P. H., & Slotow, R. (2017). Electrifying the fence or living with consequences? Problem animal control threatens the long‐term viability of a free‐ranging lion population. Journal of Zoology, 301(1), 41-50.

Trouwborst A. et al. (2017). International law and lions (Panthera leo): understanding and improving the contribution of wildlife treaties to the conservation and sustainable use of an iconic carnivore. Nature Conservation, 21, 83-128.

Yamaguchi N., Haddane B. (2002). The North African Barbary lion and the Atlas lion project. Int. Zoo News, 49, 465–481.