A feature post by WReN member , Bini Claringbold (she/her)

Warning: this article contains instances of homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia as well as discussion about conversion therapy.

When I came out, roughly five years ago now, I was well aware that it was a turning point in my life. When I entered the world of STEM as a chemist, the same feeling was present. The two decisions would (and will continue) to make a huge impact on my life. And yet, even now, there are still lots of issues that come with being both LGBTQ+ and part of STEM, although a lot of improvements and progress have been seen in recent years, which gives me hope for the future.

At the beginning of this year, I saw research carried out by Dr. Erin Cech and Dr. Tom Waidzunas that examined inequalities faced by those within the LGBTQ+ STEM community, which comes to the conclusion that those who are openly LGBTQ+ are at a disadvantage in STEM compared to those who are not. When looking at this information it came as no surprise to me honestly; anyone who is an LGBTQ+ person in STEM could have told you the same thing. Whilst the paper itself only looked within the United States, I believe the problem is prevalent globally and throughout our careers.

Firstly, I think this is an issue that starts in the earliest stages of a STEM career, and this is backed up by recent studies. Research carried out at Montana State University found out that after four years of college, approximately 7% of gay students were less likely to stay in STEM as opposed to their heterosexual peers. The case is similar within the UK, with a study from the University of Exeter finding that men in same-sex relationships are less likely to have a STEM degree or work in a STEM occupation compared to those who are in ‘different-sex’ relationships. Surprisingly, the same study showed no difference between women, which I find interesting as a pansexual woman myself.

So far, we’re not off to a great start, and things don’t improve upon entering the workplace, with the UK government’s 2018 LGBT Survey showing only 2.2% of all participants were in a ‘Professional, Scientific or Technical’ role. I would take this with a pinch of salt, as the results may be skewed given the fact that other sectors may also offer scientific roles (for example 12.4% of participants were in an educational role which could include everything from science teachers to astrophysics lecturers) but it is still disheartening to see. Similarly, in the US, LGBT people are underrepresented in STEM, and those in the workplace report that they do not have the adequate resources to succeed in their jobs.

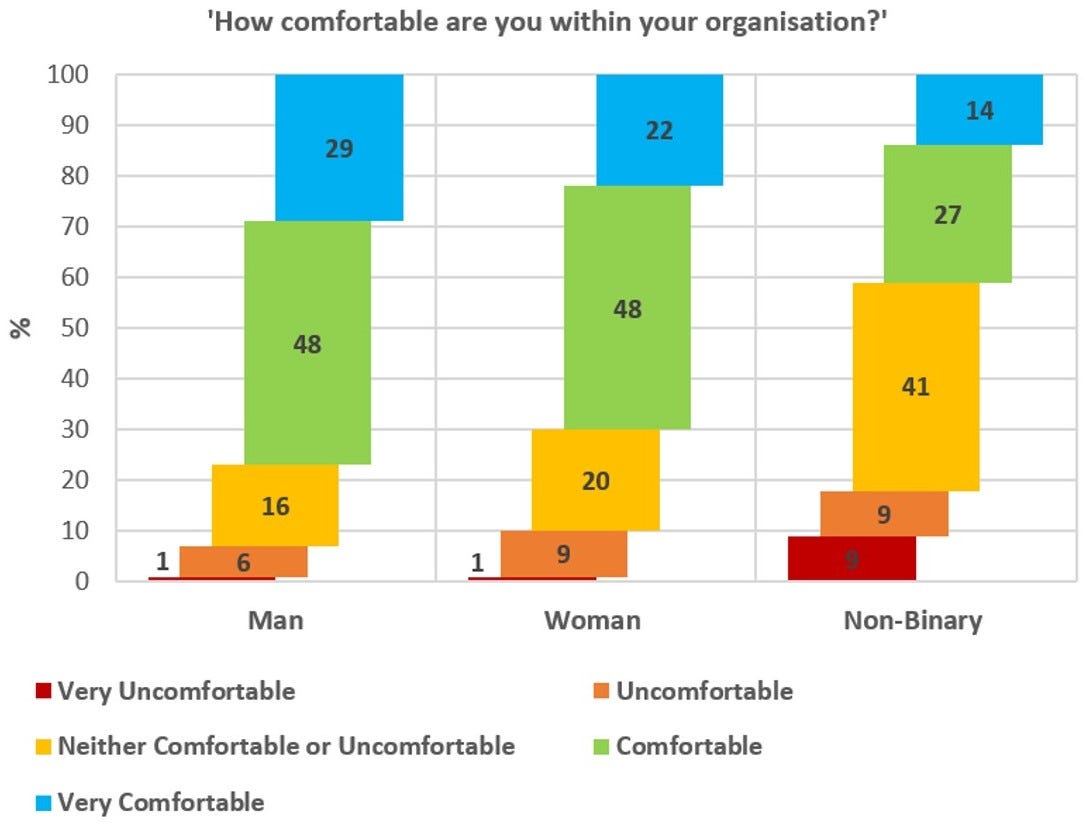

Looking at the issue in more detail, a study from June 2019 between the Institute of Physics (IOP), Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) and the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) shows the LGBTQ+ community are uncomfortable at work or experience some form of harassment (Figures 1 and 2). 28% of all LGBTQ+ scientists and, unfortunately, over half of transgender scientists had considered leaving the workplace because of the work climate and/or discrimination, and 20% had frequently considered leaving their workplace. In addition to this, significantly more LGBTQ+ scientists had experienced harassment or exclusionary behaviour, with those being transgender or non-binary suffering from this the most. As a chemist, I myself was saddened to see that chemistry had more instances of exclusionary behaviour compared to physics or astronomy.

I am not showing you these facts to shock or scare you, but only if we are fully informed can we work to improve things. Also, I am not sure how aware those who are not LGBTQ+ would be of any problems at all. This is showcased in the IOP, RAS, and RSC study, as almost half of all participants said there was a lack of awareness towards LGBTQ+ issues within their workplace. It is a bit cliché but ignorance is bliss, and if you are not directly affected by discrimination it can be easy not to know it is happening. Whilst there are already groups and networks dedicated to all aspects of LGBTQ+ STEM life, including raising awareness and fighting against these issues, there is always work to be done.

Visibility

A big part of growing a community within STEM is showing people that we exist. Visibility is encouraging for anyone who isn’t comfortable being openly LGBTQ+ (whether because it’s unsafe, or they haven’t fully come to terms with their sexuality, or something else entirely). There are challenges faced with being openly LGBTQ+, as we’ve already seen. For one, society is assumed cisgender and heterosexual unless told otherwise — we have to start the conversation to discuss sexuality openly, which might not be right for everyone. Unlike things such as gender or race, sexuality is an invisible difference, something to be declared in order to have it known.

The heteronormative nature of STEM leads to many feeling invisible or feeling like STEM isn’t very LGBTQ+ friendly, and I feel STEM as a whole can be a little behind the times at points. Indeed, this is the same area that only last year published a peer reviewed paper that declared diversity in the workforce was bad for research, and women participating in science ‘diminishes the contributions of men’. Thankfully, many were appalled by these opinions and the paper was redacted soon after, but this mentality is not uncommon, especially in the physical sciences, so where do we even begin when talking about sexual orientation in STEM?

I have never been a target of outright harassment, so I can’t imagine how hurtful it is to be, for example, dead named or misgendered, but I have had to deal with micro-aggressions that people think are okay. I am pansexual, but originally came out as bisexual, and so that comes with a whole hoard of people demanding to know if you’re more inclined to be gay or straight. Whenever you enter a relationship, people deem it fine to declare ‘oh she was just [gay/straight] the entire time because she’s now in a relationship with this person’. Whilst it makes me laugh to think of doing this to heterosexual couples, ‘oh wow you really were straight this whole time!’ in reality you would never do this to a heterosexual person, ever. It can be minor, but these small actions can add up and have a huge impact on the lives of LGBTQ+ people. These micro-aggressions exist everywhere, be it in the workplace or in education. I wish non-LGBTQ+ allies, or everyone really, was aware of how much damage this does to people after having to deal with it repeatedly; once everyone is on the same page, we can build a system where we dismantle our preconceptions from the bottom up.

A survey from the American Physical Society found that 30% of participants felt there was pressure to stay closeted, with 40% thinking their workplace expects them not to act ‘too gay’. When interviewing various queer people about their identities in STEM, a study from 2019 showed that, as well as reports of homophobic and transphobic targeting, many felt they have to hide who they really are in order to thrive in their place of work. Andi*, a mechanical engineering PhD student, was told not to come out by his supervisor. Andi questioned it, “Is this like an order? Is this I can’t come out or I will get fired?” And he wouldn’t say anything about it. He just said “you shouldn’t do this. You should not tell other people.” And it destroyed my productivity.” Statements like this are ones that I find the most frustrating; being LGBTQ+ is both not a choice and a core part of our identity, and yet we are told continually to keep it quiet or tone it down because other people think it will be better for us. For many in the study, visibility would be a large part of improving these problems. Walt*, an entomologist in the private sector, said “the only way we’re going to get ahead is if some people are willing to [be out]. There are not enough role models at all in sciences I think that are LGBT.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities and privacy of those involved in the study

People would be happier in an environment that allows them to be who they are, so the tension created through harassment or even lack of awareness can cause a problem not only for individuals but I believe for the whole STEM community. It has been shown that a more diverse group of thinkers offer more creative solutions to problems and therefore would produce better research, yet people are continually discriminated against on the basis of sexual orientation. When Nature interviewed six LGBTQ+ scientists, many of the participants repeated the same thoughts for improving the field, be accepting, practice at the things you don’t understand (like use of correct pronouns), and provide an inclusive space at work. Sean Vidal Edgerton, co-founder of 500 Queer Scientists, described it best:

“It would benefit everyone in academia if we could dismantle heteronormativity, systemic racism and white supremacy. It would allow every single individual in STEM to bring their entire selves to their career and would set everyone up for success — not just a select few.”

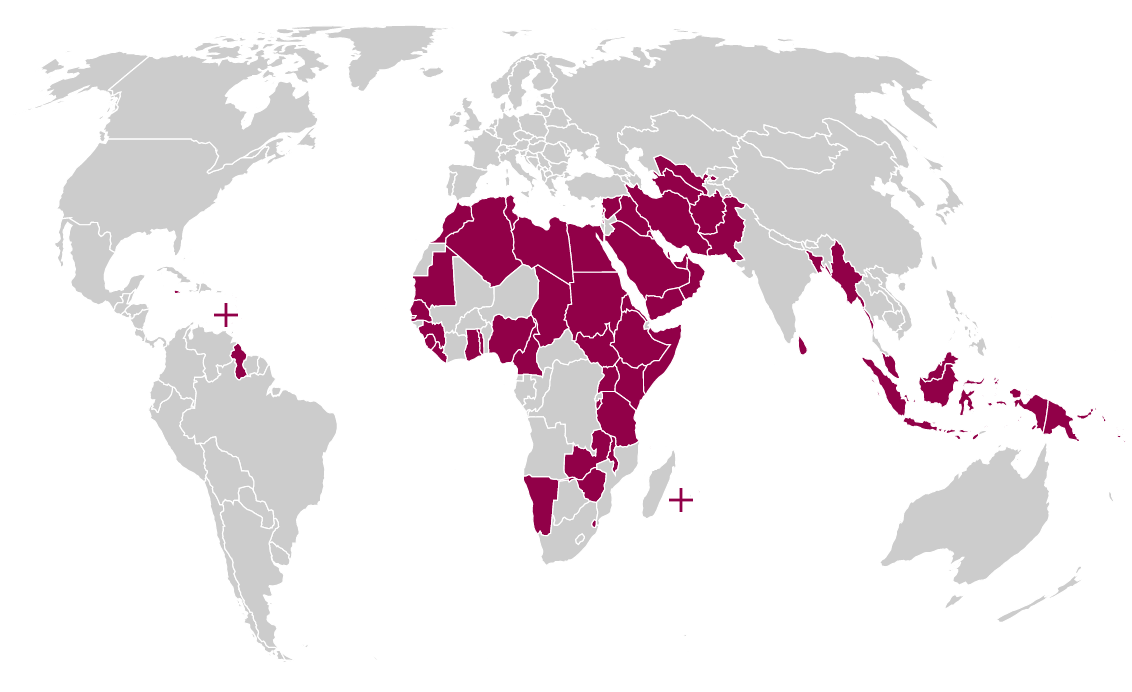

STEM is also a global field, and collaboration with others is common practice. Whilst the pandemic might have slowed it down, international conferences and talks are something that are part of being a researcher and will be again in the future. To be open and proud of your sexuality is to put yourself at a disadvantage. For example, say you were doing work that involved collaborating in Malaysia for a couple months. Malaysia currently imposes prison sentences for those involved in same-sex relationships, and the prime minister openly stated Malaysia ‘cannot accept same-sex marriage.’ Indeed, the very act of being in a same-sex relationship is described as ‘against the order of nature’ within Malaysian law, and violations of this have recently resulted in two lesbian women being caned and four men being thrown in prison for six months. It’s also a country where 45% of people agree that non-heterosexual orientations should be criminalised. I would not feel okay if it was me heading over there (thankfully this is not a case of personal experience), but other people don’t get to avoid this obstacle so easily. This is not one special instance either, there are up to 72 countries that impose some sort of punishment for being LGBTQ+, up to and including the death penalty.

There are also little things that many people (even LGBTQ+ people) might not think about; did you know only 9 countries in the world have bans of conversion therapy written into law? Four of those are South American, and only two (Germany and Malta) are European. A few more have banned medical professionals from practicing it but the practice itself is not illegal. When you see this, what message does that send about the countries that allow it, even if the topic is being contested? For comparison, only 20 states in America have completely banned the practice, less than half of the country, which suggests a majority that does not mind the abuse of LGBTQ+ individuals due to their conceptions of non-heterosexual people as individuals to be ‘cured’. As for the UK, whilst Prime Minister Boris Johnson says the practice ‘has no place in this country’ and described it as ‘abhorrent’ to date the government have only promised to have a ‘consultation’ about the practice, while A ban on conversion therapy in the UK has been touted since 2018. How confident can you be with what I would consider to be empty promises?

Ignoring the extreme cases, there are countries where it is not illegal to be LGBTQ+, but this does not stop the prejudice and discrimination against the community. Trump tried his hardest to deny rights to those on the LGBTQ+ spectrum, from banning transgender troops from the military, to allowing healthcare providers to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. President Biden is working to undo this, appointing Dr Rachel Levine as assistant health secretary, and undoing the military trans ban, but the damage has been done. Everyone over the past four years who felt emboldened to voice their anti-LGBTQ+ opinions still exist, so as a result the USA to me feels like a hit-and-miss place where LGBTQ+ safety is dependent on the state you’re in at the time.

Within Europe, in Poland, three women have been put on trial for carrying LGBTQ+ posters, and I don’t feel comfortable going to any country that has ‘LGBT-free’ zones, a complete 180 from a country that was one of the first to decriminalise homosexuality in Europe in 1932. In the UK, homophobic hate crimes are on the increase, from 2014–15 there were just over 6,600 hate crimes reported, between 2019–20 that number trebled to just under 18,500. People are suffering from verbal abuse, like the gay couple in Devon who were called ‘abhorrent’, or worse, like the case of the two women on the bus in London, being harassed and then attacked after refusing to kiss each other on their way home. Whilst these examples are not representative of those countries as a whole, it still presents a problem for LGBTQ+ people globally.

Therefore, even in countries non-LGBTQ+ people might look at and not think twice about going to, there is a lot for the LGBTQ+ scientist to take into consideration, including our own safety and wellbeing in some places. These are things that no non-LGBTQ+ scientist ever has to consider before going to a conference, or to work in another lab. They have the advantage of existing within the status-quo, whereas we will always be working our way up to equality.

Community

Now, I am accentuating the negative to make a clear and obvious point: we are a long way off from equality in general, let alone those equality for those who work in STEM, but it’s not all bad news. January showcased a good start to 2021, with Wiley’s change to their author name change policy. This would allow for the easy change of an author’s name on previous work, something I hope becomes the norm across journal publishing in future.

Small things also make a big difference: displaying pronouns (on emails, on your company’s websites, in your Zoom or Teams name tag, when you’re writing, etc) creates a more welcoming atmosphere, LGBTQ+ mentoring schemes would help students who were just starting out in STEM, or even those who hadn’t come out yet, and things like educating non-LGBTQ+ staff help makes everyone aware of LGBTQ+ issues. Another thing I personally think is a big step forward is to have accountability. We need to establish spaces within work and education where people feel safe speaking to others (including official complaints) about any discrimination or harassment. I have already spoken about the heteronormative nature of STEM, but I feel this atmosphere pushes people away from feeling confident in speaking about any aspects of their sexuality, and so when things go wrong, they’re less likely to speak up. This is also seen time and time again in all the studies noted above, LGBTQ+ people in STEM feel less comfortable.

Events and gatherings also allow people all over to come together. One thing that surprised me about the IOP, RAS, and RSC survey was that a large proportion of people who worked as teachers or in industry (people outside of academia) were unaware that organisations or networks existed that offered support to LGBTQ+ scientists. I know there are plenty of organisations that all seek to increase visibility, introduce people to LGBTQ+ scientists and showcase their work, as well as highlighting struggles people are facing.

Pride in STEM is run by LGBTQ+ scientists across the world, and they host Pride in STEM day annually on November 18th, where a series of speakers address different challenges faced within the community.

500 Queer Scientists is specifically a visibility campaign that want to showcase LGBTQ+ STEM stories.

Out in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (oSTEM) is a mostly US based society for LGBTQ+ scientists, run by students and professionals alike.

The STEM Village is a Scottish based community that hosts talks from the LGBTQ+ STEM community in order to improve visibility and form a widespread community.

LGBTQ+ STEM is another network that’s main aim is visibility, in order to show the diversity of roles LGBTQ+ people can hold in STEM.

These organisations are helping to improve the landscape for the next generation. This year was the first time I’d ever attended the LGBTQ+STEMinar, which was an amazing place for people to meet and discuss their work together. The STEM Village hosted a virtual symposium in August 2020, and this was attended by over 700 people, including those from countries where it is unsafe to be openly LGBTQ+.

As the pandemic forces us all inside, we need a community more than ever, and it’s sad to think about those who don’t know where to start. Surely, more can be done to reach those people who would no doubt benefit from the one thing we all want: an accepting community of colleagues. Even if you aren’t aware of any of the organisations above (and if you’re curious I highly recommend checking them out), there are other alternatives. Personally, I am most open about things related to being a pansexual scientist when I am on Twitter, and here I can easily find others who are part of the same community. I am sure there are other online spaces as well where people can be more open and make friends with likeminded people.

As we are in June, Pride Month, a time where we can celebrate LGBTQ+ rights and communities, we have to be aware of how far we are from equality at the moment. Now is a time to use the past and reflect on how to improve LGBTQ+ life within STEM, because whilst a lot has been achieved now is not the time to become complacent. I am thankful that we seem to be getting to a place where those looking to a future in STEM have role models and people they can look up to, and places where they can feel safe and accepted. Hopefully this is a momentum that keeps on going, as I look forward to seeing the developments to come!