Simon Black –

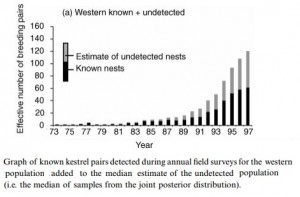

The recovery of endemic bird species in Mauritius has been notable in enabling the downlist of several Mauritian species on the IUCN Red List. In the case of the Mauritius Kestrel and the Pink Pigeon the recovery was from a handful of surviving individuals. How has this level of recovery been possible?

Carl Jones, who has led the Mauritian programmes for over 30 years, was quick to enhance his own knowledge of kestrel breeding with techniques which had previously proven successful in efforts in New Zealand and the USA. He has used a better way. Instead of imposing a command-and-control structure on his teams, he has developed a ‘system’ and more importantly, he appears to be applying systems thinking in the way that he manages the team. Every part of the system; habitats, diet, supplementary feeding, breeding facilities, nest locations, monitoring, predator eradication, bird behaviour, technical skills, equipment.

Carl Jones, who has led the Mauritian programmes for over 30 years, was quick to enhance his own knowledge of kestrel breeding with techniques which had previously proven successful in efforts in New Zealand and the USA. He has used a better way. Instead of imposing a command-and-control structure on his teams, he has developed a ‘system’ and more importantly, he appears to be applying systems thinking in the way that he manages the team. Every part of the system; habitats, diet, supplementary feeding, breeding facilities, nest locations, monitoring, predator eradication, bird behaviour, technical skills, equipment.

When we look to other sectors we see approaches which are reminiscent of the Mauritian philosophy. To some extend the levels of improvement seen in the GB cycling team over the past 10 years are a comparative illustration.

“We considered everything, even the smallest improvements, to give us a competitive edge. It was the accumulation of these small details that made us unbeatable.” Dave Brailsford, Team Chief, GB Cycling – Gold Medal winners, London 2012 Olympics

So what does this mean for us in pursuing changes and improvements in our own conservation projects? It suggests to me that any organisation would benefit from a culture of learning and continuous improvement; work on what you CAN influence in the reasonable hope that it will overcome the factors over which you have no influence. Carl Jones puts this down to understanding the species, their ecology and threats. As Juran (1989) said – focus on the vital few rather than the trivial many to achieve your purpose then, as Senge (1990) urges, always keep an open mind to unexpected outcomes and be ready to understand what else needs to be done to improve.

It is the size of influence which is important. The smallest things can be significant influencers. Conservation leaders need to be ready to spot and act upon opportunities when they arise.

Reading:

Groombridge, J.J., Bruford, M.W., Jones, C.G. and Nichols, R.A. (2001) Evaluating the severity of the population bottleneck in the Mauritius kestrel Falco punctatus from ringing records using MCMC estimation. Journal of Animal Ecology, 70, 401-409

Juran J. (1989) Juran on Leadership For Quality, The Free Press, NY

Senge P. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, Doubleday, New York.