– Simon Black

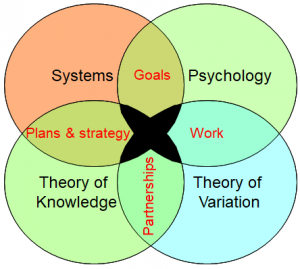

A recent paper by Straka et al (2018) suggests that cultural considerations have not been well examined in conservation leadership literature. Whilst in the broadest terms this may be true (they systematically reviewed 15 paper is total), they miss one theme which I push consistently when working with international groups of conservation leaders. The start point for any human interaction at work (and that includes leadership, of course) is meeting people at the common point of interaction for all cultures; DIGNITY.

This has been mentioned by others as a new way to consider how conservation professionals should work with local communities (Mattson and Clark 2011). If we accept others, even if their world view is very different from our own, we have a chance to communicate. If we communicate we can understand because we build our own knowledge (if we are open minded) and can build the knowledge of others (if we are clear and unambiguous). This allows us to open up new possibilities in our own minds.

Straka et al (2018) suggest it appears similarly important that training programs in conservation leadership and conservation science acknowledge, promote and use cultural diversity to inform effective leadership practices. This may be true, but the same can be said about being better at mathematics – if you pick the wrong technique, no matter how good you are at it, you will fail. We really do need to understand effective leadership practices and ineffective leadership practices and use that knowledge to develop good leaders. We already know a lot more about what works and what does not than might be generally recognised.

We need to take care to deal with inequity and imbalance in gender in leadership roles. The problem comes when barriers are presented, as often experienced by women, which preclude them from leadership roles, or make their experience in the role one where their time and energy is wasted on irrelevant prejudicial behaviours of others. We need the best leaders, whatever the gender, and the barriers that exclude women are also likely to allow inappropriate people to get into leadership in their place.

As it turns out, the best blend is with a mix of people; gender, background, discipline, culture, thinking processes – diversity adds value. But these are just ingredients – you also need method and the difference between a good approach and a bad approach is a gulf of effectiveness. You cannot, as a leader, simply ‘do the wrong things righter‘. We need to be more clever than that.

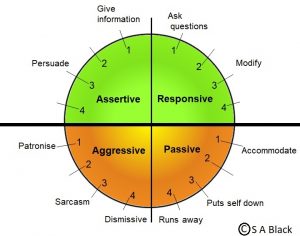

It is not a question of understanding the intricacies of different cultures (although that will help, of course). It is a matter of having an approach that cuts through those differences. So it is not about being seen as ‘strong’ or ‘weak’ by certain cultures, or being ‘participative’ or ‘dictatorial’ by some, or ‘informal’ or ‘formal’ by others.

It is also certainly nothing to do with being ‘motivational’ or ‘transformational’ – these are buzz words which mean little in practice.

For an effective leader it is a matter of being purposeful and getting colleagues to realise that they too must be purposeful. If we act with integrity and communicate to understand and seek knowledge, then we can make progress whatever our world view.

Reading

Black S.A. and Copsey J.A. (2014) Purpose, processes, knowledge and dignity are missing links in interdisciplinary projects. Conservation Biology 28 (5): 1139-1141 DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12344

Mattson, D. J., and S. G. Clark. 2011. Human dignity in concept and

practice. Policy Sciences 44:303–320.

Straka, T. M., Bal, P., Corrigan, C., Di Fonzo, M. M., & Butt, N. (2018). Conservation leadership must account for cultural differences. Journal for Nature Conservation.