I had only been working at Kent about a month when I found, by accident, a book to get thoroughly overexcited about. If you study Ancient Greece and Rome, then Plutarch’s ‘Lives’ are a selection of sources you use almost continuously, and there is, happily sitting on a shelf in the pre-1700s collection of Kent’s Special Collections and Archives, a quarto edition from 1676. Considerably more impressive than my own third or fourth hand 1950s Penguin paperback.

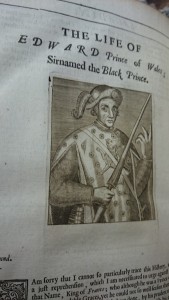

As you may know, Plutarch was a Greek historian and biographer, born at the height of Imperial Roman power, who later became a Roman citizen. His ‘Lives’ are his most famous work, and consist of biographies of prominent Greeks and Romans, with one of each being paired together to highlight their shared virtues and vices. Thus, Theseus is paired with Romulus, and Julius Caesar with Alexander the Great. This particular edition also contains various ‘Lives’ by other authors, including those of Homer, Edward the Black Prince, and Plutarch himself.

The book includes a beautiful frontispiece, central to which is a portrait of Plutarch flanked by a Roman and a Greek with an angel positioned over all three. Under this are smaller pictures, two of cities, supposedly Rome and Athens, although their accuracy can certainly be doubted, one of sailing ships and one of a battle scene. Inscribed above the frontispiece in manuscript is the name Samuel Davie.

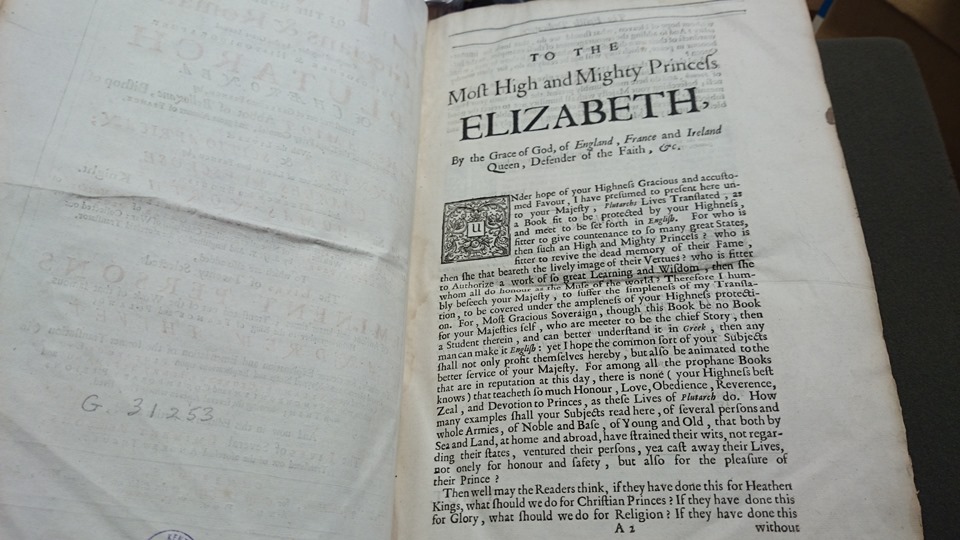

A section of the book I find particularly fascinating is the dedication “to the Most High and Mighty Princess Elizabeth,” Queen of England. Sir Thomas North, the translator of these lives from French to English, was a captain in the English army during 1588 when the Spanish Armada sailed for Britain. In 1591 he was knighted. The first edition of these Lives was published in 1579, and the dedication appeared then. In this dedication he praises her lavishly, to an excessive level even, saying she ‘can better understand [Plutarch] in Greek, then any man can make it English’ and begs her to accept this dedication, after all ‘who is fitter to revive the dead memory of their Fame, then she that beareth the lively image of their Vertues?”. He holds up the people written about as examples that ordinary men should look upon as inspiration to do everything in their power to serve their queen. I can’t help but think that such flattery probably served him well on his way to a knighthood.

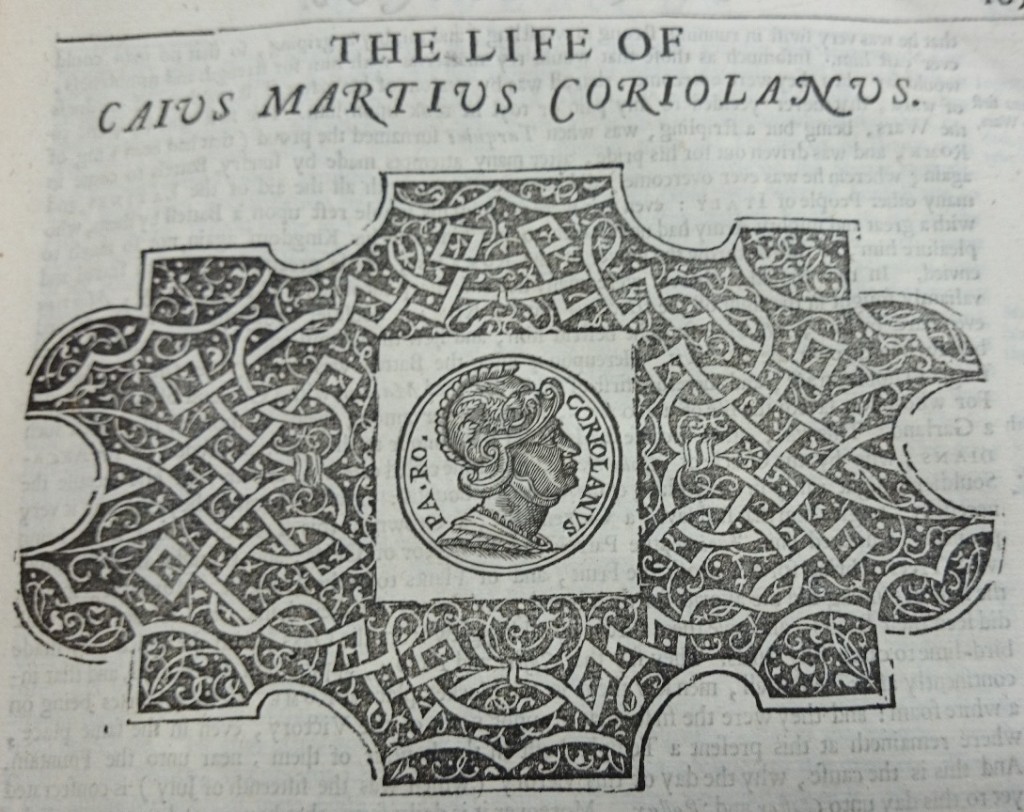

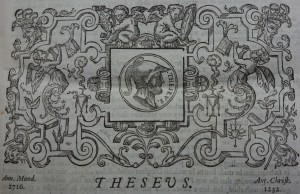

Portraits of all the subjects can be found at the start of each of the ‘Lives’. The most elaborate of the illustr ations to Plutarch’s work is that of Theseus, who opens the book. The surroundings of his portrait are more detailed than the others, involving much plant life and several cherubs, where others consist of geometric shapes. The later ‘Lives,’ not written by Plutarch, also include portraits, these are larger and more detailed.

ations to Plutarch’s work is that of Theseus, who opens the book. The surroundings of his portrait are more detailed than the others, involving much plant life and several cherubs, where others consist of geometric shapes. The later ‘Lives,’ not written by Plutarch, also include portraits, these are larger and more detailed.

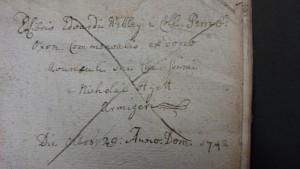

The book appears to have had several previous owners. Other than Samuel Davie, we find other inscriptions on the front pastedown. The book was once part of the library of Edward Webley of Pembroke College Oxford, a gift from his friend  Nicholai Hyett, dated 29th October 1742. Turning the flyleaf reveals yet another name, possibly that of Nicholas Webb. The book was bequeathed to the University of Kent by a Miss Margaret Ley. We have no information about Margaret Ley, so if anyone out there knows who she is, we’d love to find out!

Nicholai Hyett, dated 29th October 1742. Turning the flyleaf reveals yet another name, possibly that of Nicholas Webb. The book was bequeathed to the University of Kent by a Miss Margaret Ley. We have no information about Margaret Ley, so if anyone out there knows who she is, we’d love to find out!

This book is just one of many books in our Pre-1700 collection, so explore more on the University of Kent library website.