Written by Eleanor Barrell, student on HI6062: Dynasty, Death and Diplomacy – England, Scotland & France 1503 – 1603

‘Musing and marveling on the miserie that doth on earth from day to day increase’. This is a serious and lengthy didactic poem titled; A Dialogue between Experience and a Courtier, of the miserable state of the worlde (1581) by the Scottish herald and court poet, Sir David Lindsay of the Mount (1490-1555).

Most commonly known as The Monarche, Lindsay’s Dialogue between Experience and a Courtier has been regarded by many historians, as his ‘magnus opus’. This is because he writes a world history in 6338 lines, beginning with Adam and Eve and concluding with the Last Judgement. He uses the classical literature technique of dialogue between the two characters called Courtier who is ‘tyred with travailing’ and ‘an aged man’ who is Experience, together with a narrative history of the world to answer questions presented by the Courtier about the fulfilment of life and salvation.

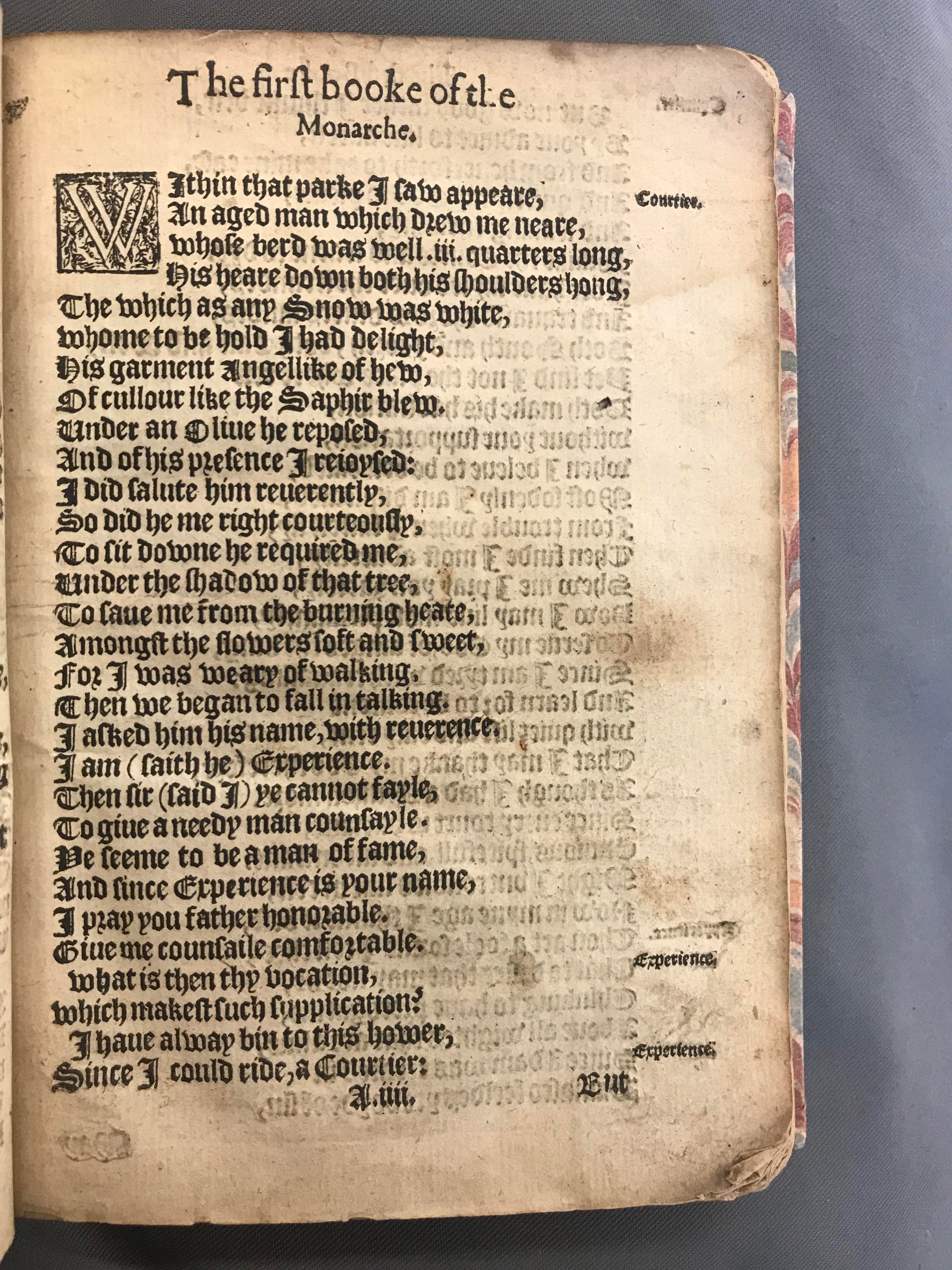

Lindsay’s Monarche reflects the knowledge that he would have had as herald about the religious and political issues in Scotland during the time. In ‘The first booke of the Monarche’, Lindsay introduces the Courtier and Experience. The Courtier asks where he can live a ‘quiet life’ away from his unpleasant life at court. Experience replies that the life he wants does not exist as the misery in this world developed from sin, he recounts the story of Adam and Eve to support his case. ‘The second booke of the Monarche’ is formed of Lindsay’s attack on idolatry of saints images, pilgrimages and finishing with a call for reform to the Church. The third ‘booke’ condemns the Church for profiting from the creation of Purgatory and temporal lands, the clergy for living wealthily and unable to fulfil their roles of office, and Rome having control over secular rulers. In the last book, Lindsay discusses ‘Death and the Antechrist, and of the generall judgment’ with the Courtier asking Experience when the day will be. Experience dates the year ‘Two thousand till the worldes ende’ but before then, fifteen signs will appear as warning. Lindsay uses the Apocalypse as the reason for the early modern world being dismal but also as another plea for reform and repentance. By raising these problems within the context of the Biblical history of the world, the push for reform is presented as an integral part of God’s scheme and the urgency to be ready for Jesus’ coming.

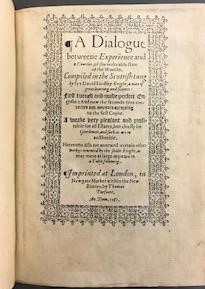

This particular book was originally ‘Compiled in the Scottish tung’ by David Lindsay in 1554, then ‘first turned and made perfect English : And now the seconde time corrected and amended according to the first Copie’ in 1581. The 1580s in Elizabethan England was briefly threatened by radical puritanism in response to a Catholic resurgence. Therefore, this timely publication (1581) could imply that there needed to be a revival of Protestant literature to communicate the original causes for condemning the Catholic Church and maintaining reform. The date also implies that the popularity of Lindsay’s book had spread to England for it to be translated out of Scots into the English vernacular, many of his previous works had already been published in England before. This also coincides with Lindsay’s opinion on vernacular which is seen in ‘The first booke of the Monarche’ where he criticises the Roman Church for not speaking in vulgar tongue during Mass as it would allow people to understand and learn what is being said. To support his argument, he uses the example of God giving the Ten Commandments to Moses not in Latin or Greek but in the ‘language of the Hebrew’ so that every man, woman and child would know the law. Lindsay is upholding his argument and deliberately writing in Scots so that his Scottish audience can clearly learn from his writing, it is easily accessible.

Front cover of book recovered in marble paper. The measurements of the book are 191(l)x138(w)x127(d)mm which indicates that it would have been an easily portable book.

In the Templeman Library’s copy, the cover is recovered in marble paper which dates to around the late eighteenth and nineteenth century and would have been a cheap covering. The original binding of the book from 1581 has been replaced by a quarter leather binding, impressed with a simple gold design and lettering. This could indicate that The Monarche was a sought after book and in need of repair or possibly the owner wanted a uniform look for their bindings when displayed on a bookshelf. Furthermore, it is clear to see that the book has been amended as the pastedown and flyleaf are at the front and back of the book are on different paper which is intact and only slightly discoloured, indicating that it is newer addition to the original text. The most fragile pages of the book have been stuck down onto a new sheet of paper. The book lacks any decorative element to it as there are no woodcuts or ornate patterns, only a decorative border around the first letter of each book, known as factotums. This might suggest that the book was made to be produced quickly and cheaply.

The title page, which has been reprinted on new paper and inserted into this 1581 published book, helpfully declares that the book is ‘very pleasant and profitable for all Estates, but chiefly for Gentlemen, and such as are in aucthoritie’. This is further supported by Lindsay explicitly showing in his fourth book, where he writes small segments for the people in authority, ‘to the Prelates’ and ‘brethren Princes’, that they may read his words and take guidance from them. This section is what the English publisher possibly had in mind when writing the title page. However, a more subtle indication that this book is aimed at a wider audience, is that not only is it written in the vernacular so that all can read but Lindsay deliberately incorporates a written world history and the Christian teachings surrounding death and the Last Judgement so that more common people could access them whilst the vernacular Bible was circulating. In Scotland, the Earl of Arran had legalised the English Bible in 1543 which enabled all men to read the bible in English or Scots but it was not printed in Scotland at all until 1579 and so the imported bibles came from England.

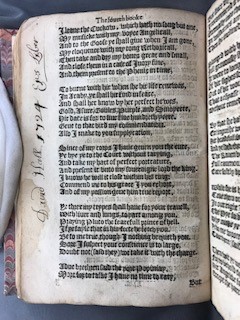

Significantly, on the back of page 13 (13b), there is the inscription that reads; ‘David Hall 1724 Eius Liber’ which is Latin for ‘his book’. Was this the David Hall (1683-1756) who was a ‘schoolmaster and Quaker minister’ from Skipton in Craven, Yorkshire? There is no other significant marginalia within the book but on a couple of pages near the back, especially noticeable on the separate poem published within the Monarche; ‘The complaynt and publique confession of the Kings olde Hounde called Bagshe, directed to Bawty the Kings best beloved Dog, and his companions’ on page 119 in the ‘The fourth booke’, and also page 64, there are pen trials. This indicates that the reader was possibly making notes on a separate page whilst reading this book or the markings could be the reader’s own symbols to draw attention to important parts of the text. This shows that Lindsay’s poem was fulfilling its function of teaching his audience, may it be his intended or unintended audience.

Bibliography

Primary Source:

A Dialogue between Experience and a Courtier, of the miserable state of the worlde by David Lindsay (London: Thomas Purfoote, 1851). Special Collections & Archives, Pre-1700 Collection: C 581 LIN

Secondary Sources:

Collinson, Patrick., ed. Guy, John. 1995. ‘Ecclesiastical vitriol: religious satire in the 1590s and the invention of puritanism’ in The reign of Elizabeth I: Court and culture in the last decade’, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Edington, Carol. 1994. Court and Culture in Renaissance Scotland: Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, (USA: University of Massachusetts Press).

Harland, Richard. ‘Hall, David (1683-1756), schoolmaster and Quaker minister’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/68171 [accessed 26/10/2018].

McGinley, J,. K. ‘Lyndsay [Lindsay], David (c. 1486-155), writer and herald’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://doi-org.chain.kent.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/16691 [accessed 22/10/2018].

Pearson, David. 2011. Books as History: The importance of books beyond their texts (London: The British Library).

Wormald, Jenny. 1981. Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland 1470-1625, (London: Edward Arnold Ltd).