Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens (1617) is one of the most intriguing early modern books held in the Templeman Special Collections and Archives. This blog post by MEMS PhD student and Knowledge Orders before Modernity Scholar, Anisia Iacob, delves into its secrets.

While the name Atalanta Fugiens might ring a bell for some, the original format is elusive to most of us who have heard of Michael Maier (1568-1622). Atalanta fugiens is an alchemical emblem book published first in 1617 by German alchemist and physician Michael Maier. The book follows the story of the Greek myth of Atalanta and Hippomenes. In Ovid’s account of the myth, Atalanta claims she’ll marry the man who could beat her in a running race. Atalanta is a great runner and, confident in her abilities, accepts Hippomenes’ challenge. Although Hippomenes isn’t a better runner than Atalanta, he uses a ruse to win the race. He drops three golden apples which he received from Venus. Distracted by the apples, Atalanta stops for a second to pick them up, and this is how Hippomenes manages to beat her and win her hand in marriage.

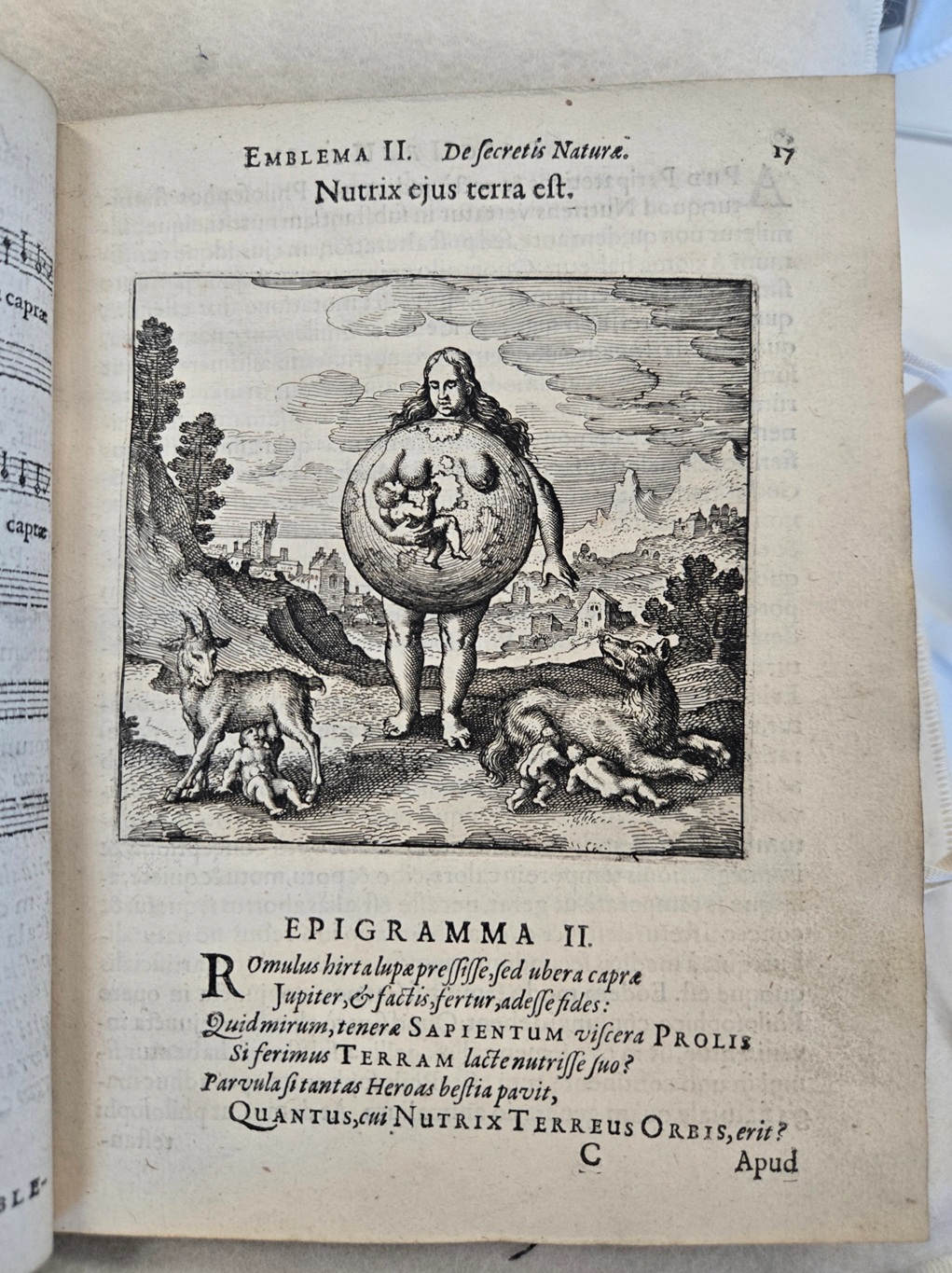

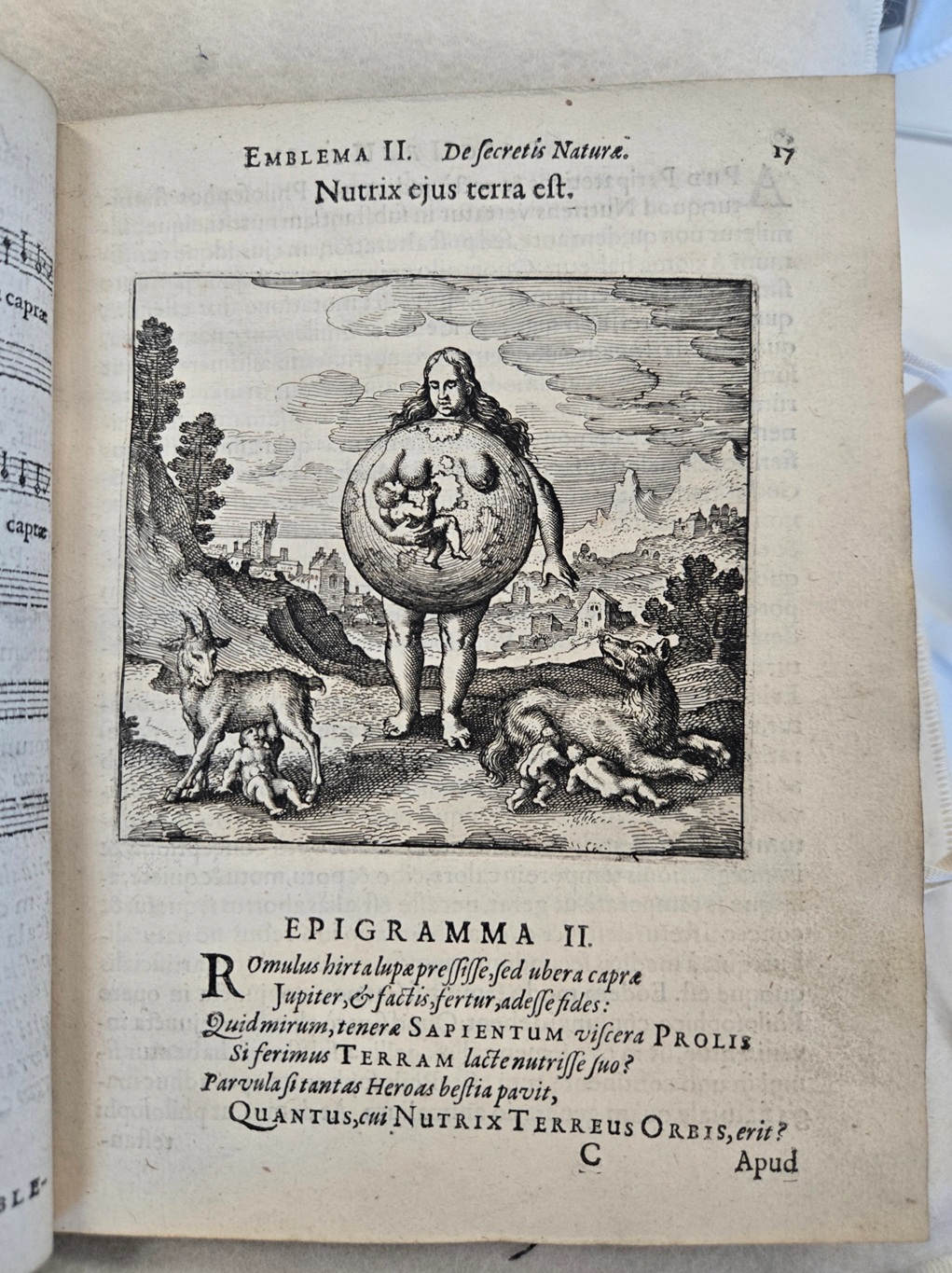

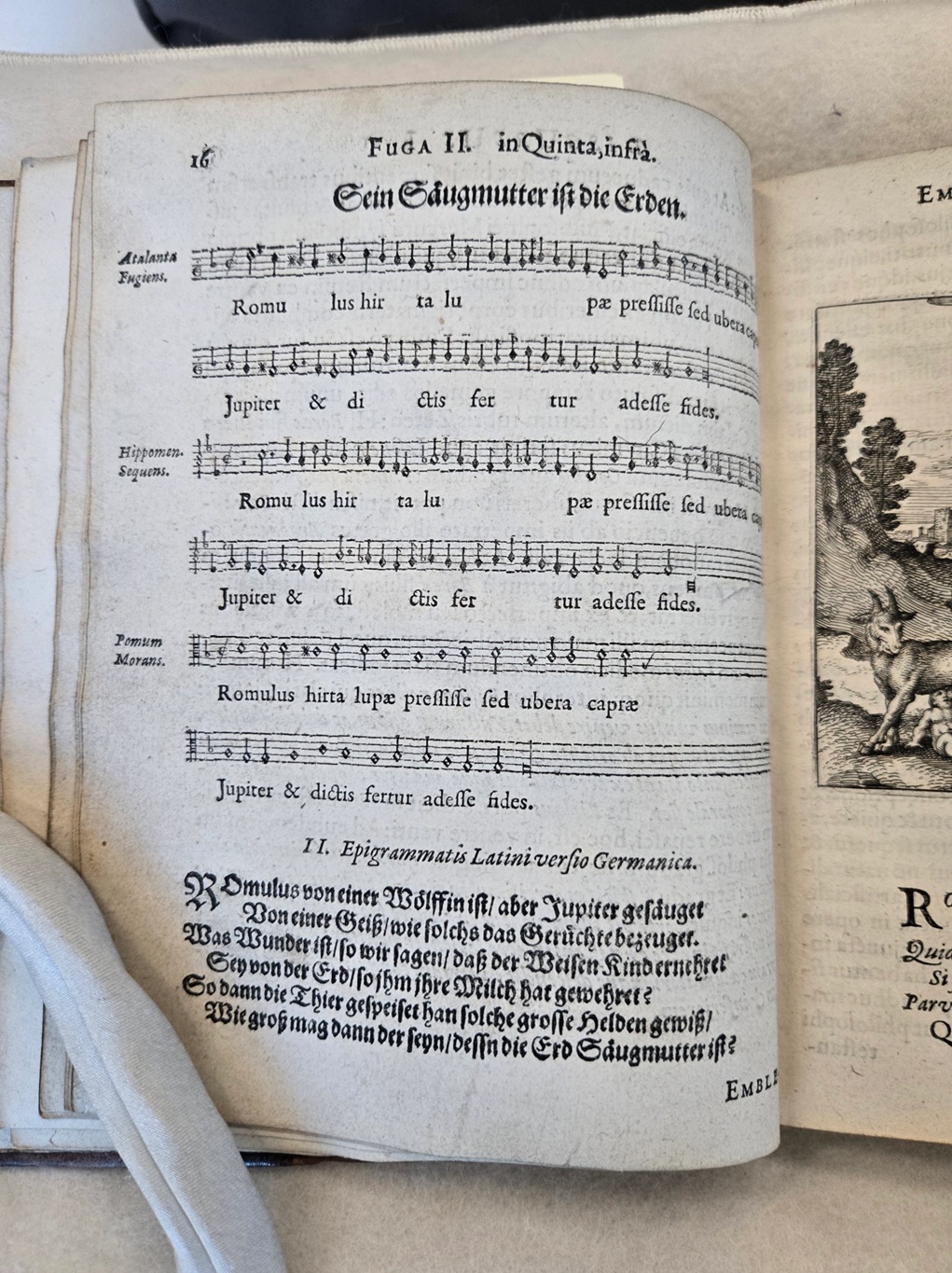

The Atalanta fugiens edition from the 1617 is a peculiar book for many reasons. It starts with a preface on ancient music and explains the Greek myth of Atalanta. The book is adorned with 50 emblems, each coming with an epigram in verse, complete with a music sheet for a fugue in three voices. Atalanta is the vox fugiens, Hippomenes is the vox sequens, and the third voice or vox morans is the Pomum objectum (the apple used as a ruse). Most likely, 40 out of the 50 fugues are based on the work of John Farmer (c. 1570-1601). Farmer was an English composer who was part of the English Madrigal School. During the Elizabethan period, he made a name for himself through his settings in four voices meant for old church songs. In 1599, he published his collection of four-part madrigals, dedicated to Edward de Vere (1550-1604). Farmer’s piece titled Divers and Sundry Waies is believed to be the inspiration for Maier’s musical pieces due to their similarities in arrangement. Besides the music and verse, each epigram is also connected to two pages of discourse where the theme of the image and song are discussed.

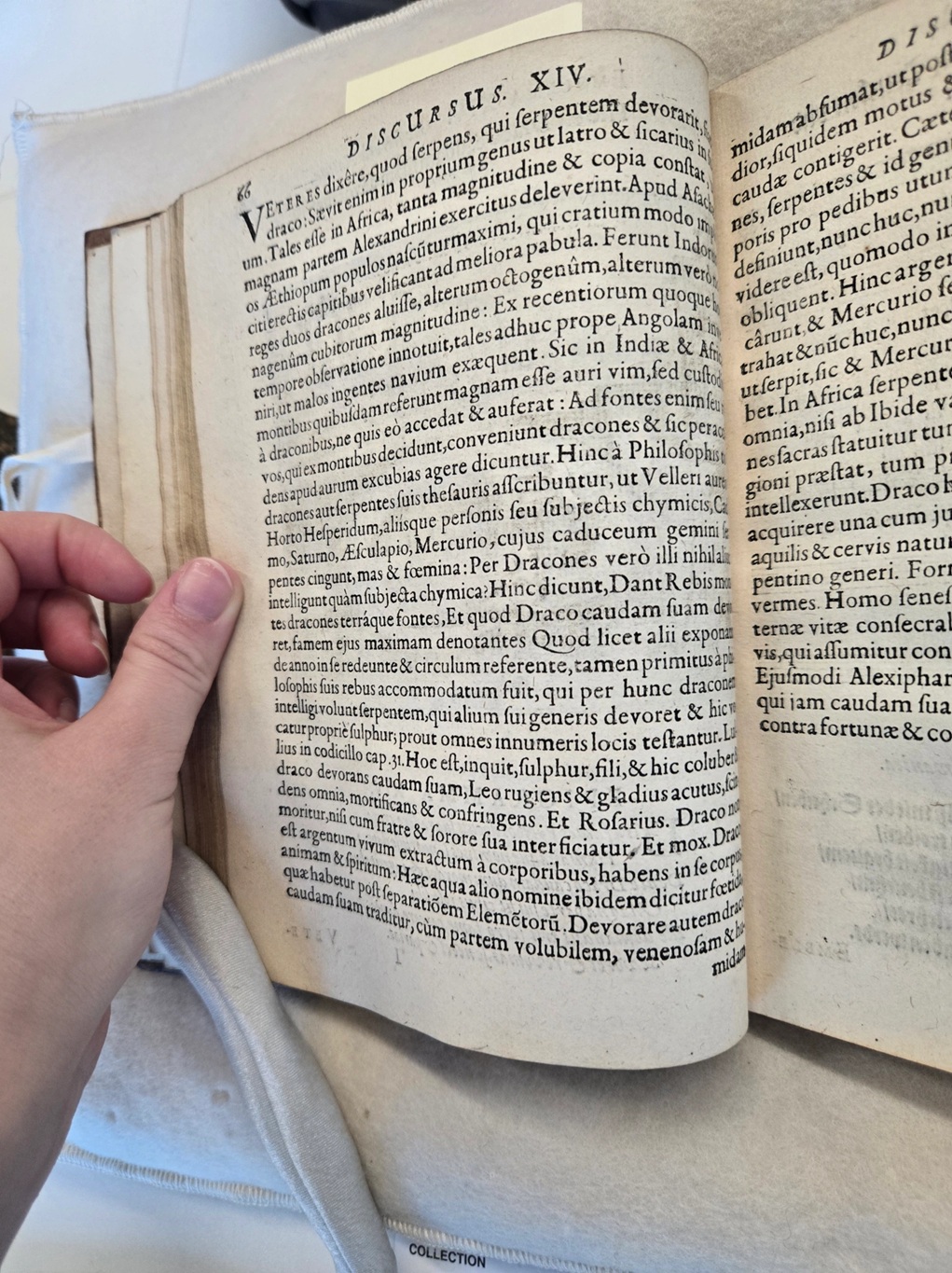

The book is written in Latin, with a height of 20 cm – making it quite easily a portable format. The engraver of the emblems is identified to be Matthaeus Merian the Elder (1593-1650), an engraver and book dealer, part of the Basel patrician family of Merian, and one of the most prominent German illustrators of the century. This present edition was published in Oppenheim, Germany, which coincides with the date of Matthaeus Merian moving to the city. He moved there in 1616 and started working immediately for the publisher Johann Theodor de Bry (1561-1623), son of popular artist and traveler Theodor de Bry (1528-1598). This means that most likely Atalanta fugiens, Maier’s commission, was one of the first projects that Merian undertook in his new role in De Bry’s workshop. Merian’s work on Maier’s book must have contributed to his reputation as a skilled illustrator for alchemical works, as he works on another similar project in 1678 for Musaeum Hermeticum. The latter publication shares page formatting similar to Atalanta Fugiens in terms of the text-image ratio and functions.

![Page ten from Lambsprinck‘s De Lapide Philosophico [On the Philosopher’s Stone] as published in the Musaeum hermeticum, reformatum et amplificatum. Engraved by Matthaeus Merian. Francofurti : Apud Hermannum à Sande, 1678.](http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/memsnews/files/2025/03/igne.jpg)

While this format was not common for most alchemical works, it’s not extremely unusual when considered in context. Maier’s career as a physician and alchemy enthusiast can be described as a constant balancing act. On one hand, it was the balance between the still-strong Galenic influence in medicine and the Greek-Roman heritage it encapsulated. On the other hand, the emerging Paracelsian framework, which was starting to impose itself as a new way of thinking about medicine from a chemical perspective. Besides this, he needed to perform a balancing act regarding theological matters. He needed to find a way between his Lutheran faith and tenets that pragmatically dealt with the world, with minimal affordances to the occult, and the alchemical possibilities of supernatural forces and realms that couldn’t be grasped through the established framework of the Reformation. Besides Atalanta fugiens being a recipe for the philosopher’s stone, it’s also a race against Maier’s times and context, a search for the right answers in a period of great changes.

If you would like to listen to the music of ‘Emblem I: The Wind Carried Him in Its Belly’, visit this YouTube video by the American Museum of Paramusicology.

By Anisia Iacob

MEMS PhD Student | KOM Scholarship Awardee

———————————-

Many thanks to the Special Collection from Templeman Library at the University of Kent for housing and making accessible such an early edition. Special thanks to Suzanna Ivanic’s Religious Materiality seminars which facilitated this finding and, consequently, this blog post.

See original post on Anisia’s website here.