Our discussion on The Crimson Field encompassed several areas: its three (or four) female heroines and some similarities to the heroines of melodrama and the gothic; other female characters; relationships between the other characters, including between the genders and within hierarchical structures; the suffering crying soldier and his connection to music; other films and TV series about women during war and pondering why the series was not recommissioned.

We began by noting that the hour was very action and character packed – despite the fact it all took place during the one day. This set up many interesting plot points and character relationships for upcoming episodes.

We thought that the first episode’s focus on three women’s journeys to, and first experience of, the field hospital echoed a similar Hollywood trope. In Hollywood films there are sometimes three main female characters with these separated from one another on the grounds of morality: one is a ‘good’ girl, one a ‘bad’ girl and the other sits somewhere in between. Each of these faces a different fate: one is usually punished (often by death), another triumphs and the third suffers but manages to go on. We commented that this links to US, and especially Hollywood films’, focus on melodrama.

In The Crimson Field, there are the posh clueless Flora (Alice St. Clair), the left on the shelf do-gooder spinster Rosalie (Marianne Oldham) and the spirited Kitty (Oona Chaplin) who is signalled as ‘bad’ through her modern habits of smoking and expressing forthright opinions. Kitty seems to be our main heroine as we are afforded some insight into her past as she throws away a ring on her boat journey. While Flora has to suffer the grim reality of bloody bandages and Rosalie is mocked for her spinster status, we are more invested in Kitty. She stands up to matron on behalf of the other women, and is later in danger as she is attacked by a patient. Her response to this is calm, forgiving, and her challenge to man to just kill her gives us some further awareness of her troubled past.

In The Crimson Field, there are the posh clueless Flora (Alice St. Clair), the left on the shelf do-gooder spinster Rosalie (Marianne Oldham) and the spirited Kitty (Oona Chaplin) who is signalled as ‘bad’ through her modern habits of smoking and expressing forthright opinions. Kitty seems to be our main heroine as we are afforded some insight into her past as she throws away a ring on her boat journey. While Flora has to suffer the grim reality of bloody bandages and Rosalie is mocked for her spinster status, we are more invested in Kitty. She stands up to matron on behalf of the other women, and is later in danger as she is attacked by a patient. Her response to this is calm, forgiving, and her challenge to man to just kill her gives us some further awareness of her troubled past.

The three heroine focus is somewhat disrupted by the arrival of a fourth. Joan (Suranne Jones), a self-sufficient qualified nurse, arrives late, dressed in a leather coat, sporting a short hairdo, and riding a motorcycle. We thought that the fact she is unmarried (such an option was not open to nurses at the time), her appearance and manner possible coded her as a lesbian. We were especially intrigued regarding the ring she wears around her neck, hidden by her clothes.

The three heroine focus is somewhat disrupted by the arrival of a fourth. Joan (Suranne Jones), a self-sufficient qualified nurse, arrives late, dressed in a leather coat, sporting a short hairdo, and riding a motorcycle. We thought that the fact she is unmarried (such an option was not open to nurses at the time), her appearance and manner possible coded her as a lesbian. We were especially intrigued regarding the ring she wears around her neck, hidden by her clothes.

While the emphasis on suffering – of both genders – points to melodrama, we also saw a correlation with some of our recent work on the gothic. The three main female characters headed outside at night, dressed in white gowns and carrying lamps, to wish the troops luck as they left for the front.

Our attention was also drawn to the two other main female characters – Sister Margaret Quayle (Kerry Fox) and the recently promoted Matron Grace Carter (Hermione Norris). Their relationship was complex. Outwardly good colleagues, there appeared to be tensions under the surface since Grace became matron despite Margaret having more experience. We also found the difference in their approaches to the new volunteers telling. While Grace was tough on them, Margaret appeared more friendly. Margaret was revealed to be hypocritical and cruel however as she commandeers Flora’s cake and despite telling her she has shared it among the men, is seen eating it secretly. More disturbingly she deliberately withholds a medical exemption from a suffering soldier meaning that he is sent back to the front. Meanwhile Grace is revealed to be caring towards Kitty after her attack, despite Kitty’s earlier disobedience.

Our attention was also drawn to the two other main female characters – Sister Margaret Quayle (Kerry Fox) and the recently promoted Matron Grace Carter (Hermione Norris). Their relationship was complex. Outwardly good colleagues, there appeared to be tensions under the surface since Grace became matron despite Margaret having more experience. We also found the difference in their approaches to the new volunteers telling. While Grace was tough on them, Margaret appeared more friendly. Margaret was revealed to be hypocritical and cruel however as she commandeers Flora’s cake and despite telling her she has shared it among the men, is seen eating it secretly. More disturbingly she deliberately withholds a medical exemption from a suffering soldier meaning that he is sent back to the front. Meanwhile Grace is revealed to be caring towards Kitty after her attack, despite Kitty’s earlier disobedience.

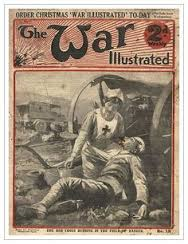

Despite the dramatic war backdrop, much of the episode is about such complex characters, their power plays ,and their battling relationships. We also commented on the kindness of Kevin Doyle’s captain Lt Colonel Roland Brett, in contrast to Colonel Charles Purbright (Adam James) forcing an emotionally damaged soldier to return to the front. Even the admirable Brett warns Matron Carter to make sure she controls the potentially ‘silly’ new female volunteers, though. This attitude fits in with the misogynistic narrative the melodrama research group has recently uncovered while researching the World War I magazine The War Illustrated. In these issues girls can be plucky and brave, but they are still kept contained. The depiction of the main heroines and other women in The Crimson Field challenges this view. (See the NoRMMA website for more on the project: http://www.normmanetwork.com/?p=604.)

Despite the dramatic war backdrop, much of the episode is about such complex characters, their power plays ,and their battling relationships. We also commented on the kindness of Kevin Doyle’s captain Lt Colonel Roland Brett, in contrast to Colonel Charles Purbright (Adam James) forcing an emotionally damaged soldier to return to the front. Even the admirable Brett warns Matron Carter to make sure she controls the potentially ‘silly’ new female volunteers, though. This attitude fits in with the misogynistic narrative the melodrama research group has recently uncovered while researching the World War I magazine The War Illustrated. In these issues girls can be plucky and brave, but they are still kept contained. The depiction of the main heroines and other women in The Crimson Field challenges this view. (See the NoRMMA website for more on the project: http://www.normmanetwork.com/?p=604.)

We were especially struck by the depiction of Corporal Lawrence Prentiss (Karl Davies) – particularly in contrast to the women. Prentiss appears to have PTSD, and is seen to be physically suffering from his war experiences. He is offered sanctuary by the colonel (who also explicitly defies an order from his superior not to reissue an exemption pass on health grounds) and is seen crying profusely as he listens to a gramophone record of Madame Butterfly. Such a depiction of the suffering male is unusual, and the understanding shown to Prentiss perhaps progressive for the time. It is possibly significant that the music has a restorative or recuperative effect because Prentiss’ emotions are displaced onto those of a woman – the suffering opera heroine.

We were especially struck by the depiction of Corporal Lawrence Prentiss (Karl Davies) – particularly in contrast to the women. Prentiss appears to have PTSD, and is seen to be physically suffering from his war experiences. He is offered sanctuary by the colonel (who also explicitly defies an order from his superior not to reissue an exemption pass on health grounds) and is seen crying profusely as he listens to a gramophone record of Madame Butterfly. Such a depiction of the suffering male is unusual, and the understanding shown to Prentiss perhaps progressive for the time. It is possibly significant that the music has a restorative or recuperative effect because Prentiss’ emotions are displaced onto those of a woman – the suffering opera heroine.

Watching the episode also prompted some discussion of other films and TV series which covered a similar topic. We mentioned the British films The Gentle Sex (1943) and Millions Like Us (1943) whose points of view were affected by their time of production. The TV series Tenko (1981-1984) about female prisoners of war was also referenced for its unusual focus on women during wartime.

We ended by pondering why the series was not recommissioned. It would have been especially apt to have it run through the 100 year commemoration of World War I. Its complex characters, and its positive view of women, provide a different view of war to the one we are usually afforded. We connected this to the BBC now moving money into such massive budget programmes as The Night Manager as it competes with Netflix and other platforms. If you’d like to see the rest of the series, most episodes are available to University of Kent staff and students via Box Of Broadcasts: https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.