The two teams from Kent were among just eight teams selected to compete. They travelled to London on Monday (3 February) to tackle a series of four legal design challenges based on the themes: protecting freedom; fighting for rights; defending democracy; and saving the planet.

Our team had a great day and was very kindly hosted by Professor Emily Allbon, from City Law School; a strong advocate for the importance of Legal Design for all lawyers in all fields, and the creator of the incredibly resourceful websites: https://tldr.legal/home.html and https://lawbore.net.

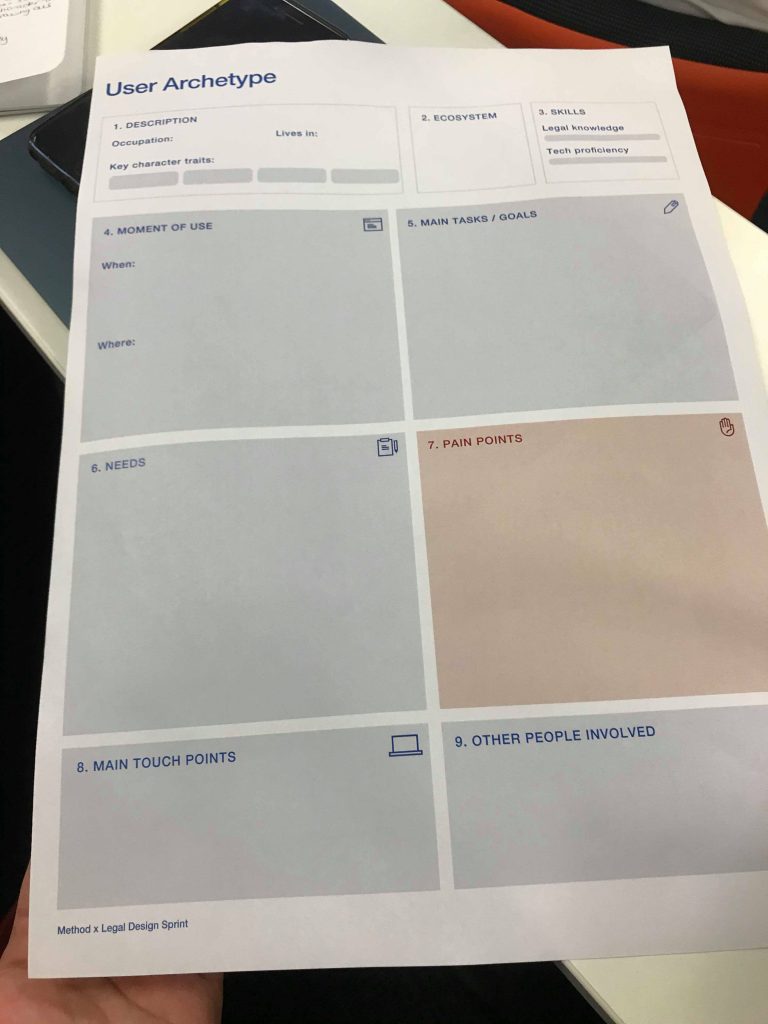

We were introduced to Legal Design through lectures interwoven with various interactive challenges, which taught us ‘legal design thinking’, and how to apply that creative methodology to our assigned projects. This methodology was inspired by Stanford Law School’s Legal Design Lab, created by pioneer Margaret Hagan, to tackle problems with legal design thinking in phases:

- Understand Phase: empathise with the users the design is being created for, and the context of the design’s use

- Define Phase: identify and qualify problems and needed solutions, while staying user-focused (human-centred design)

- Develop Phase: ideation (stream of consciousness concept brainstorming) and prototyping of designs + user testing

- Deliver Phase: refine design prototypes – weave a story/narrative with the design idea and how it developed to final product

Our assigned challenge: Working with the Public Law Project (founded to help the marginalised destitute and disadvantaged hold public authorities accountable); we are tasked with creating an accessible explainer for people who are going through the process of judicial review, often without legal support.

Through the challenges and following the legal design thinking phases, our team identified three big challenges to the accessibility of judicial review:

- Unawareness: Most laypeople have no idea that judicial review exists as a recourse to rectifying an injustice by a public body they may have suffered

- Mystification: Even once aware of judicial review, many would-be users of the complex process are intimidated by the daunting prospect of going through court and potentially losing

- Access to justice: For litigants in person already in a judicial review, the process is often still intangible and nebulous, and even after a judgment is given, the real-life effect may not be easy to grasp, so that a concrete sense of justice can be quite elusive through this legal tool

After having created archetypal user personas of people who may be able to use judicial review, and ideated possible design ideas, our team prospectively settled on perhaps designing an informative graphic E-Flyer and pitching it with an awareness campaign to ‘Democratise Judicial Review’! Although we are still brainstorming…

I personally have found my work as a legal research assistant to Professor Amanda Perry-Kessaris last June to be particularly useful. I applied for Kent Law School’s Legal Research Assistantship Scheme, which I found to be an amazing experience, especially since you are paired with a professor whose work appeals to your interests. I highly recommend the scheme to students potentially interested in legal research, doing a postgraduate degree or entering academia after graduating.

Professor Perry-Kessaris has pioneered the application of ‘designerly ways’ to legal research, and a better understanding of her work and a masterclass on Legal Design can be found by reading two of her most recent articles:

- Perry-Kessaris, A. (2019). Legal design for practice, activism, policy and research. Journal of Law and Society [Online] 46:185-210. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12154.

- Perry-Kessaris, A. and Perry, J. (2019). Enhancing Participatory Strategies With Designerly Ways for Sociolegal Impact: Lessons From Research Aimed at Making Hate Crime Visible. Social and Legal Studies [Online]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3387479.

I personally worked with Professor Perry-Kessaris on her new Legal Design book Doing Sociolegal Research in Design Mode to be published by Routledge, and which is supported by a Leverhulme Foundation research fellowship. The book’s thesis is that ‘designerly ways’ can help enhance socio-legal research, mitigate risk within research, and make that research more ‘social’, using Manzini’s ‘design mode’. A brief summary of Professor Perry-Kessaris’s project is available online.

Professor Perry-Kessaris has drawn on Ezio Manzini to propose that design-based methods can legal researchers to be more or differently:

- Practical: able to make things happen

- Critical: able to identify what is or ought to be acceptable

- Imaginative: able to see what does not yet exist ‘

Her works seeks to show that critically applying ‘designerly ways’ to socio-legal research can help make that research, and law generally, more ‘visible and tangible’, thereby offering a ‘structured freedom’, in which legal practice, activism, policy and research can be ‘at once practical, critical and imaginative’, while attempting to stress the importance of mitigating risk (such as bias) within law.

I personally find Legal Design to be a very innovate, creative and modern cutting-edge tool for all lawyers in all fields, with any interests and a wide applicability to all work. Legal Design is more than a methodology; it is a lens that can be applied from the most simple problems to abstract ‘thinking about thinking about thinking’, to quote Professor Perry-Kessaris. Legal Design is a means of self-expression and making law more accessible and diverse.

I have applied to do a research Master’s in Law in Comparative Constitutional Socio-Legal Design after I graduate from my Law & Criminology LLB this summer, and in my research proposal, I made a strong use of the application of legal design methodology to Günter Frankenberg’s ‘IKEA theory’, which I hope to test as a platform for conceptually redesigning constitutional paradigms.

Research Title: Innovating Günter Frankenberg’s IKEA theory: Redesigning Constitutional Paradigms

Research Abstract: Constitutional governance is becoming increasingly globalised. In response to the subsequent debate between comparative legal functionalism and culturalism, Günter Frankenberg’s IKEA theory posits the existence of a ‘collective constitutional consciousness memory’, ‘emanating from processes of transfer’, which ‘functions as a reservoir’, like in an IKEA supermarket. Due to the challenge of illiberal constitutionalism and nationalist resistance against the globalisation of legal systems, I propose an inquiry into the question: how could Frankenberg’s IKEA theory be innovated as a critical platform for the redesigning of constitutional paradigms? My proposed research falls between an intersection of Comparative Constitutional Law and the application of a socio-legal design influenced methodology to the IKEA theory. The aim of this study would be to find how the IKEA theory could assist in innovating, modernising, and challenging constitutional archetypes, such as bi-cameral parliaments.

Legal Design has been transformative in my academic development, and I hope to learn more about it so that it can of further use to me in my goal of pursuing a PhD following my master’s research. I am excited to work with my team and the Public Law Project to win the Legal Design Sprint, and am grateful to the Bar Council and City Law School, as well as Kent Law School of course, for giving us this amazing opportunity.

I hope this blog post is useful to law students who didn’t know about Legal Design, or the opportunities offered by Kent Law School for future legal researchers. For the curious who want to learn more, here are some very useful links:

- https://tldr.legal/home.html

- https://blog.lawbore.net

- https://amandaperrykessaris.org

- http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries/

- https://law.stanford.edu/organizations/pages/legal-design-lab/

- https://www.legaldesignalliance.org/resources/

Daniel Rozenberg