Professor George Saridakis from Kent Business School provides insights on the Coronavirus outbreak.

The coronavirus outbreak has severely hit the leading industrial nations; up to now, the G20 countries comprise nearly 71 per cent of the total number of deaths globally. Four of their members, United States, United Kingdom, Italy and France (also members of the G7 group) are currently the ones with the bigger share (comprising together 60 per cent of total deaths). Moreover, many other wealthy European countries such as Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland have experienced a significant number of deaths. Spain alone nearly accounts for 13 per cent of the total deaths worldwide.

How do European countries perform?

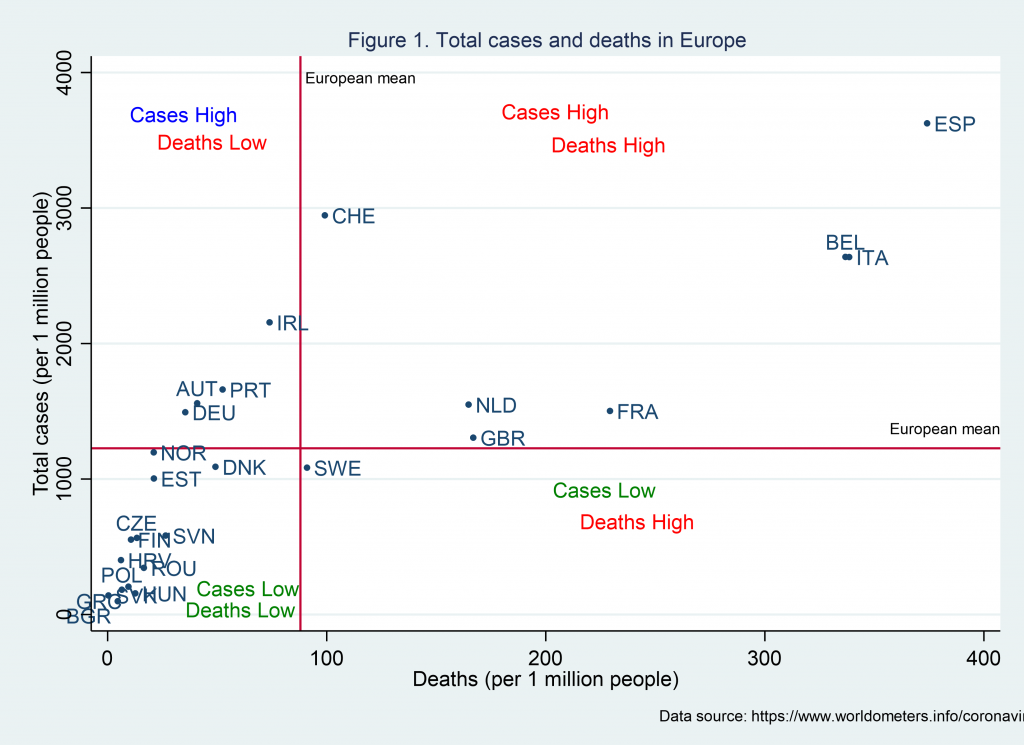

Figure 1 provides a picture of the current situation by identifying four groups of countries. At the bottom left, there are several countries (including, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Slovakia) that have total cases and deaths (per 1 million people) below the European average. At the bottom right, there is a single country, Sweden. As the graph shows, it has just started to surpass the European mean number of deaths, making Sweden the country with the greatest number of deaths among the Nordic countries. On the top left panel, there is a group of countries that, despite many confirmed cases, are experiencing relatively low death rates to other countries. Austria, Germany, Ireland and Portugal have prevented a deadly tragedy so far, most likely due to the timing and/or type of measures they have introduced. In contrast, the top right includes countries that have experienced many cases, as well as a high number of deaths (e.g. Italy, Spain, United Kingdom). Of course, the interpretation of the data should be viewed with caution since different countries may have different reporting, detecting and recording mechanisms and also the intensity of tests varies.

Why some countries perform better than others?

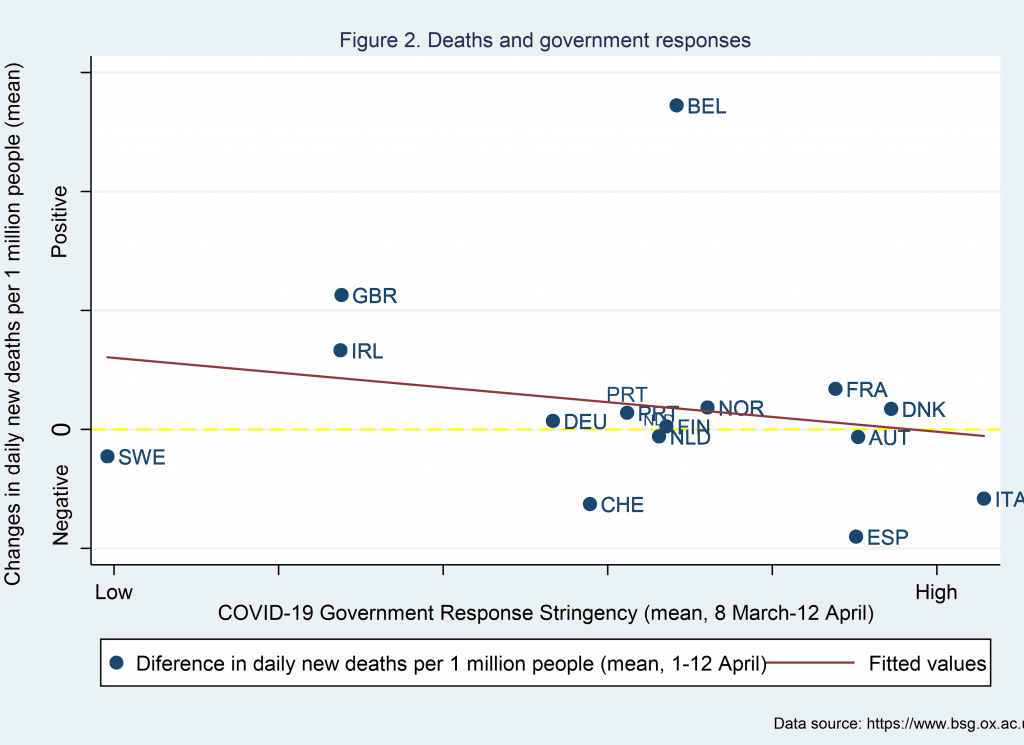

European countries have taken several measures and approaches to protect their citizens. Most of the European countries, however, have followed a well-planned, timed and executed (partial or complete) ‘lockdown’ to protect their citizens. This becomes even more crucial in a period when the health care system is not at its fittest following the spending cuts and capacity reduction as a result of the most recent financial crisis [for more information see State of Health in the EU for various countries by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)].

Have the stringency measures had an impact on the spread of the virus?

Why has Sweden followed a different approach?

Sweden, in contrast to other European countries, has adopted a more relaxed strategy. One may be related to the characteristics and culture of the population. The Swedish population, for example, has the lowest rate of smoking and a below-average rate of obesity in Europe (factors that may reduce the risk of an adverse health outcome if infected). Another factor may be related to the robust health care infrastructure, provision and resources. According to the OECD State of Health report (2020), it has one of the highest health spending in Europe, and a high number of doctors and nurses. However, Sweden is faced with a limited number of hospital beds and delayed discharges, which may be act negatively in a scenario of excessive demand for immediate health care attention.

Should policy makers turn the focus and resources on testing for COVID-19?

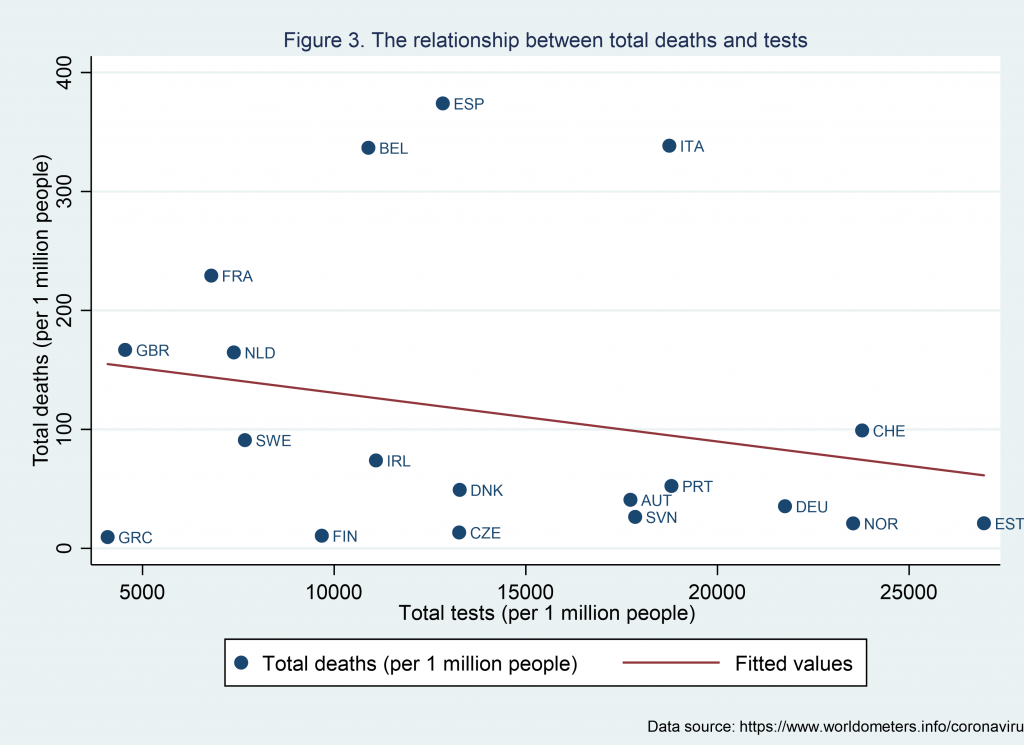

Testing for COVID-19 can be a useful instrument for medical experts and analysts to understand the virus, but it can also be a helpful instrument to policymakers. There are various reasons which may lead one to suggest this since it can contribute to timely diagnosis and thus assist in protecting the population through contact tracing and self-isolation. It can also help policymakers and advisors understand the magnitude of the problem and the virus spread in society or community clusters and extract useful information (e.g. fatality rates), which can then be used to adapt government policies and strategies.

During this pandemic, which countries have invested in testing, and how do they do relative to other countries? As we can see from Figure 3, there is a potential negative relationship between death rates and test rates. Bringing information from Figure 1, we can see that countries with high cases and low deaths (e.g. Austria, Germany and Portugal and to a lesser extent, Ireland) have invested in the testing policy. Also, in the group with high cases, Switzerland is the one with lower casualties but also the one with the highest number of per capita tests. The United Kingdom is among the countries with the lowest population testing.

What is the way forward?

We live in an international socially and economically driven world, and if we wish to maintain this level of interaction, we need to fight the coronavirus jointly and not individually. The success of one or few countries will just add a short-run benefit for those countries since there will be unavoidable spill over effects as government measures are relaxed. We are only as strong as the weakest link. Lockdowns seem to be an efficient short-run strategy to control and limit the spread of the virus and avoid mass demand for immediate health care provision (and hence, protect the health care system). This is not the cure for the problem and a prolonged lockdown can have severe consequences on the economy; an OECD evaluation of the impact of COVID-19 ranges between 20-35% of GDP for European countries.

A strategy based on the hope of a quick medical miracle or the potential effect of improved weather conditions can lead to over-optimistic expectations amongst people and change their distancing behaviour. In contrast, as medical scientists walk the rocky road of finding the vaccine and/or drug (for all of us), governments, in my view, should invest in mass testing of the population along with a carefully crafted strategy of a gradual lockdown exit. This may potentially allow less risky aged cohorts with certain health and social conditions (e.g. living with no elderly or caring individuals) to re-enter the normal flow of life.

Although this goes beyond my capacity to suggest, health experts and governments may also consider the mask policy for certain outdoor activities, crowded places and public places and transportation, as raised in recent empirical evidence and discussions (for a summary see Using face masks in the community by OECD, 2020) to reduce potential transmission from asymptomatic individuals. Perhaps this becomes even more essential as most countries lack significant testing capabilities of the population. However, five European countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Lithuania) seem to have adopted such a policy.

Joining forces and resources make it more likely to overcome this health struggle, and protect our people, societies and economies. It is time to act together with one policy and one target. We need to fight this strategically before it overtakes us and becomes a severe problem, especially for poorer parts of the world, where the health and welfare systems may not be able to provide the necessary support and thus can lead to devastating consequences for the world’s population.

For more information on our MSc programmes such as International Business Management, Healthcare Management or Management please view our programme pages in the links provided.