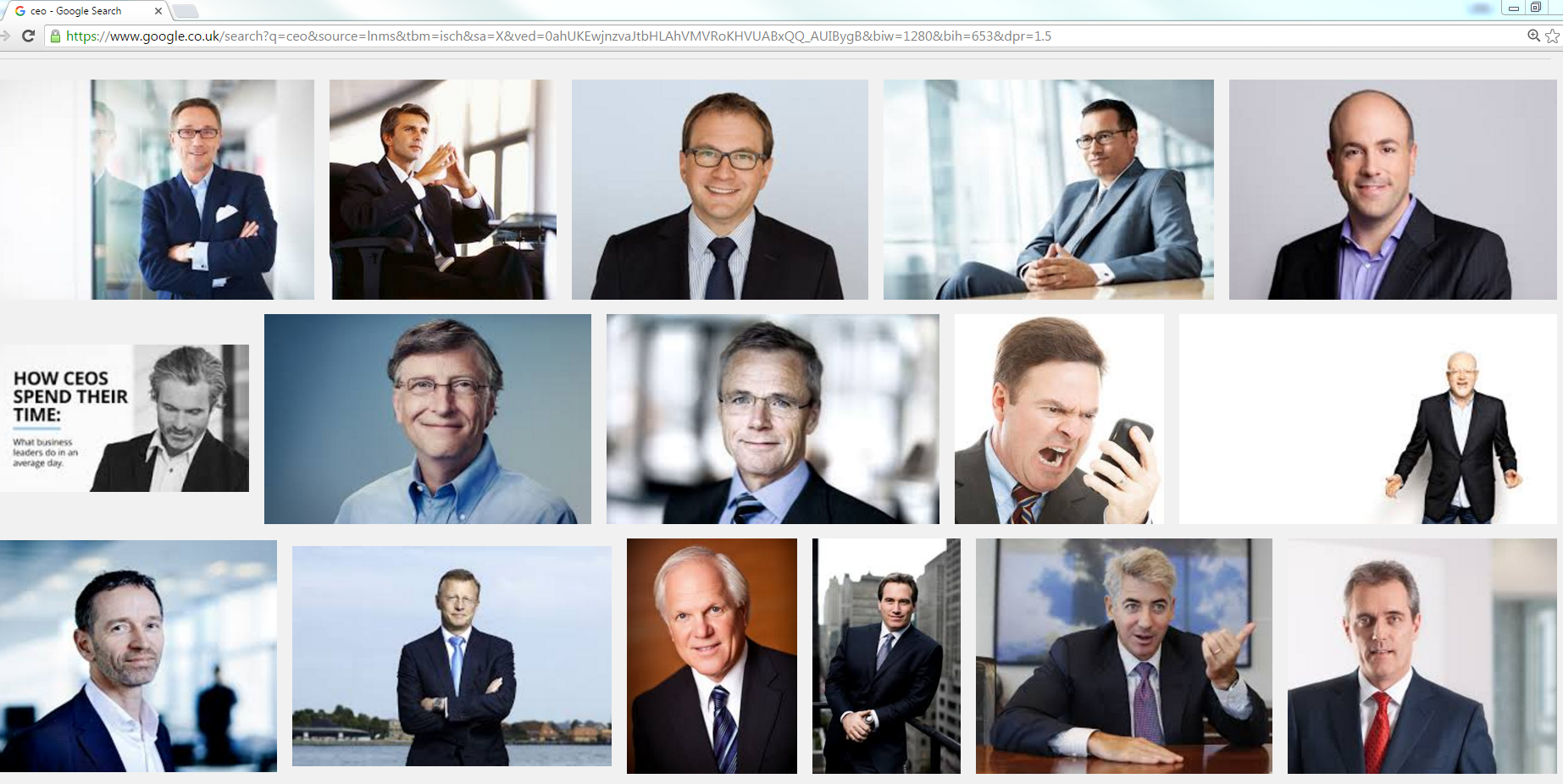

The statistics on women’s progress to the top of the executive ladder suggest her presence there is a rare phenomenon. A search on Google Images for “CEO” provides an easy visual of the domination of men at the top. Less than 10% of executive directors at FTSE 100 companies are women and there are only five women occupying the role of CEO in these organisations (fewer than the number of men called Dave). Men are also 4.5 times more likely to reach the executive group than women in the same peer group.

If the glass ceiling still exists, the question has to be, Why?

Credit Suisse Research issued a report on gender diversity and corporate performance in 2012 which states:

“In testing the performance of 2,360 companies globally over the last six years, our analysis shows that it would on average have been better to have invested in corporates with women on their management boards than in those without. We also find that companies with one or more women on the board have delivered higher average returns on equity, lower gearing, better average growth and higher price/book value multiples over the course of the last six years.”

Based on the available evidence it would be difficult to argue against the fact that an equitable gender mix improves organisational performance. And more women than ever before are gaining the professional qualifications required to run corporations. Significantly, in 2015 women represent the majority of applicants to both Master of Accounting and Master in Management programmes (GMAC Application Trends Survey Report, 2015). But the UK (along with the rest of the world) is still failing to generate a robust pipeline of female business leaders.

Part of the problem could be denial. The UK Government is reporting the success of its voluntary Women on Boards initiative. Run by Lord Mervyn Davies (now being replaced by Sir Philip Hampton), this voluntary scheme had a modest target of 25% representation of women on FTSE 350 boards. This has taken five years to achieve and conveniently includes the largely peripheral role of Non-Executive Directors, obscuring the fact that female Executive Directors represent less than 10%.

The 30% Club has undoubtedly had some success in raising awareness of the gender gap, acquiring high profile members such as Aberdeen Asset Management, Aviva Investors and Standard Life Investments. Despite not wanting to criticise the schemes in place, the group does acknowledge that it would take 75 years to reach gender parity on corporate boards if the pace of change does not improve.

The fact is that UK boards remain highly ambivalent (without penalty) to the issue of gender inclusion and the rate of change is implacably glacial in its progress.

If we agree that it’s good for organisations to have more women on executive boards and that there are ambitious women qualified to do the job, then where does the problem lie?

One answer is the nature of corporate culture. Dr Patricia Lewis, Reader in Management at Kent Business School, and experienced researcher and writer in the broad area of gender and organisation studies states,

“Female leaders are particularly challenged in that they achieve success only when they display the assertive masculine behaviours required to run big corporates. But this has to be balanced with the feminine characteristics expected of the female gender.”

Dr Lewis cites the example of Harriet Green, the now legendary saviour of Thomas Cook, who became CEO in 2012 and took the share price from a flailing 13p to over £1.70 in 12 months. Despite achieving exceptional performance she left the company after only two years, following disagreements with the group’s directors. They met for dinner without her on a Sunday evening and unanimously decided Harriet’s time was up. It seems the old boys’ network simply didn’t like her “alpha-(fe)male” persona. The more the media showcased Harriet, her personal brand and her success, the more the Thomas Cook elite wanted to distance themselves from the feisty, tough and bombastic executive. Would a male boss have been treated in the same way?

It’s important to recognise that not all potential female CEOs are the same as Harriet Green. Her style was authentic to her, but it is a style that is more masculine than feminine (at least in public). By her own admission she is competitive, single-minded, impatient and supremely confident.

Although high-profile American executive Sheryl Sandberg, tells us to “Lean In” and take a seat at the table, it is more comfortable for many of us to wait for an invitation. Should a domineering and pushy approach be a requirement for C-suite success?

For those of us with more typically feminine and even post-feminist personalities, can we reach the top without changing? Or are we destined to either opt-out, balancing family life with a start-up in cupcakes, or stagnate in a middle management role?

To coincide with International Women’s Day , Kent Business School is hosting the second ESRC-funded seminar on Contemporary Gender Roles, Identities and Expectations at Work on Wednesday 9 March 2016. Leading academics in the field of gender studies will shine a light on the topics discussed above. Why not start your own conversation?